Stay always informed

Interested in our articles? Get the latest information and analysis straight to your email. Sign up for our newsletter.

As EU Climate Commissioner Wopke Hoekstra gets ready to lead the 27-country bloc’s delegation at this year’s UN climate talks, COP28, questions remain over whether he is fit for the job. New research by Corporate Europe Observatory shines a light on why his 11 years at the consultancy firm McKinsey could cast serious doubt on his ability to represent the European Commission, and the interest of all Europeans seeking to avoid climate chaos, especially given the consultancy’s prominent role at COP28. Despite Hoekstra’s public commitment to do so, he has not disclosed the list of his clients he worked for while at McKinsey. Will his ties to big polluters prevent him backing the European Parliament’s call to protect the talks from fossil fuel industry interference? Or will his ex-employer influence his decision-making? At a minimum, he must disclose his clients and connections to McKinsey.

Wopke Hoekstra, the Dutch centre-right Deputy Prime Minister, was appointed EU Climate Commissioner in October 2023 with questions still swirling over his commitment to the climate, given his pro-fossil fuel track record (see box). There were also questions over his political independence, given the lack of transparency during the years he worked for McKinsey & Company before and during his time as a Dutch Senator (2011-2017). This is despite his promise to disclose his clients to the European Parliament.

Hoekstra has never attended the UN climate talks, but new research from Corporate Europe Observatory shows McKinsey and its fossil fuel clients have historically been very involved. The role and influence of the management consultancy firm in the global climate policy-making sphere is both ubiquitous and insidious. The firm advises both fossil fuel companies and governments, with its staff jumping into public office and back again. Currently, McKinsey & Company is advising the COP28 Presidency, allegedly in the interests of its fossil fuel clients rather than the climate. Given Hoekstra’s long-standing links to the company and senior staff members, this poses a potential conflict of interest for the EU Commissioner.

Hoekstra’s pro-fossil fuel past

During his private and political career of more than 20 years, Hoekstra has no track record of promoting or pushing for policies and measures that contribute to solving the climate crisis. He also has no experience in international climate negotiations.

Instead, and worryingly, he has a track record of working for over 15 years, up to 2017, with corporations that promote fossil fuel interests – first Shell, and then McKinsey.

In 2017, Hoekstra went from being a Senator (and McKinsey partner) to being appointed Minister of Finance in the Netherlands (until January 2022, when he became Foreign Minister and Deputy Prime Minister). While Finance Minister, he argued against rapidly ending gas exploitation in Groningen, despite the massive negative impacts gas drilling had on hundreds of thousands of citizens.

Earlier this year, Hoekstra, as leader of his political party CDA, personally blocked Dutch government plans to reduce nitrogen emissions, that aimed to bring national policy in line with EU legislation on nature protection.

As Finance minister he provided €3.4 billion in support to aviation company KLM during the COVID19 pandemic, without attaching any environmental, climate or other conditions to this package.

McKinsey is notoriously tight-lipped about its client list – but its company website says that in “the past 5 years, we have advised 55 percent of the world’s top 20 oil and gas companies on capital productivity, on more than 285 projects spanning all major hydrocarbon basins.” A 2021 New York Times (NYT) investigation revealed that in recent years, McKinsey has advised at least 43 of the 100 biggest corporate polluters, including BP, Exxon Mobil, Gazprom and Saudi Aramco. And based on the 2022 NYT journalists’ book ‘When McKinsey comes to town’, the firm’s work for Chevron alone generated at least $50 million in consulting fees in 2019, and McKinsey has “continued to acquire new fossil fuel clients, making them more profitable and more efficient at extracting carbon from the ground.”1

Despite the ongoing lack of transparency about which clients the EU Climate Commissioner worked for while at McKinsey, it is very clear that the consultancy firm has worked for some of the world’s biggest oil and gas companies. While Hoekstra heads to COP28 leading the EU delegation – the first UN climate talks he will attend – his former employer and its clients are regular participants at COP, with intimate knowledge of the process and how to push their agenda.

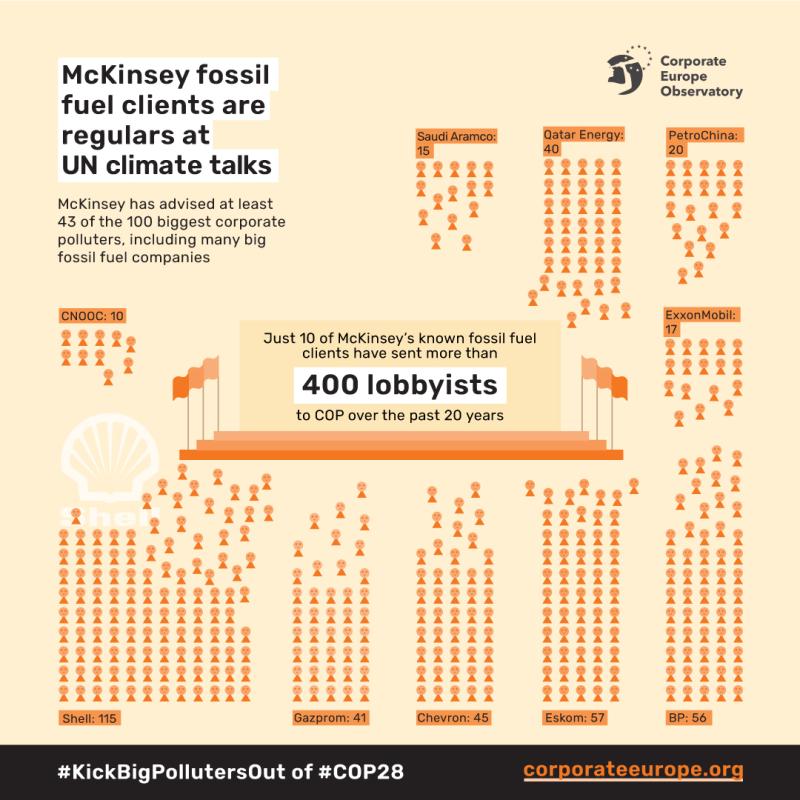

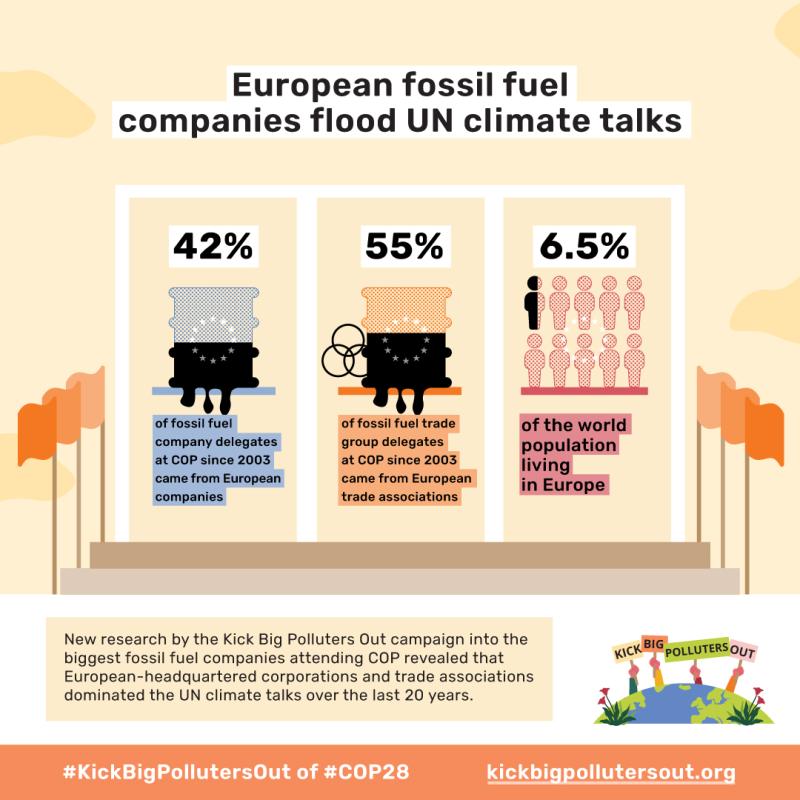

Research published by the Kick Big Polluters Out campaign, representing more than 450 organisations across the world, looked into big polluter participation at the UN climate talks over the past 20 years and found more than 7,200 fossil fuel lobbyists had attended the negotiations. Building on this research, Corporate Europe Observatory found that 10 major fossil fuel companies known to have been clients of McKinsey & Company have sent at least 416 individual representatives to the UNFCCC climate talks over the past two decades. These McKinsey clients are Shell, BP, ExxonMobil, Chevron, Gazprom, Saudi Aramco, Eskom, Qatar Petroleum, China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC).2

Many of these companies have pushed false solutions like carbon markets, Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) and hydrogen at the climate talks. These are all fossil-friendly techno-fixes and market mechanisms that fail overwhelmingly from a climate justice point of view, and are incompatible with a rapid and just energy transition. For example, Shell’s Chief Climate Adviser David Hone (who has attended 17 COPs in the last two decades) has boasted about how Shell influenced the outcome of COP21 by securing the inclusion – and influencing some of the wording – of the Paris Agreement’s Article 6 on carbon markets. This article paves the way for oil companies to keep drilling for fossil fuels, so long as they buy carbon offset ‘credits’ – regardless of their efficacy, or the impacts that offset projects have on frontline communities in the global south. David Hone also spoke at a European Commission-hosted event on the EU’s own carbon market, the Emissions Trading System (ETS), in the EU Pavilion at COP21 in Paris. He claims that the EU’s position “is not that different from how Shell sees this.” Shell now has another ally in its ex-employee Hoekstra, who in his first public grilling told MEPs, “I have a confession to make: I’m in love with the ETS”.

McKinsey itself is also a major promoter of fossil-friendly false solutions, and of continued oil and gas extraction. A recent AFP investigation found that McKinsey has been using its position as a key advisor to the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the host of this year’s climate talks, to push the interests of its big oil and gas clients. Sources said McKinsey is "vocally and brazenly calling for lower levels of ambition on oil phase-out at the highest levels within the COP28 presidency". A McKinsey COP28 energy scenario suggested $2.7 trillion annual investment in new oil and gas was necessary until mid-century – a claim that is terrifyingly at odds with the International Energy Agency’s declaration that no new fossil fuel investments can be made if we want to limit global heating to 1.5 degrees. McKinsey’s own website describes how at COP28 the firm will “collaborate with business, government, and civil society leaders to devise transformative climate solutions”, and “convene senior executives for a series of events in Dubai”. This includes a panel on the role of oil and gas in the energy transition with senior oil and gas executives from the US, Europe, Africa and the UAE.

McKinsey’s involvement in the September 2023 African Climate Summit in Nairobi has likewise been criticised by African civil society organisations, for shaping the agenda to focus on gas as a transition fuel, carbon markets, and other false solutions like carbon removals. The agenda, under McKinsey’s influence, reflected the interests and priorities of the Western corporations the firm represents rather than the continent’s interests or priorities.

McKinsey’s pro-fossil fuel agenda is also clearly against the goals of the EU, which committed to the Paris Agreement, and in particular to keeping global temperature rise below 1.5 degrees. As the European Parliament’s COP28 resolution makes clear, that means phasing out all fossil fuels. In this context, given Hoekstra’s long-standing relationship to McKinsey, serious questions should be asked about his suitability to lead the EU at COP28. Even before he was confirmed in post, more than 100,000 people signed a petition saying he was unfit for the job given his fossil fuel promoting career, while 50 NGOs called on the European Parliament to reject his nomination as Climate Commissioner. As Hoekstra heads to a COP where McKinsey is advising the host country, has an active presence on the ground alongside many of its clients promoting their fossil-friendly false solutions, is it realistic to believe that he will not be influenced by more than a decade working at the firm?

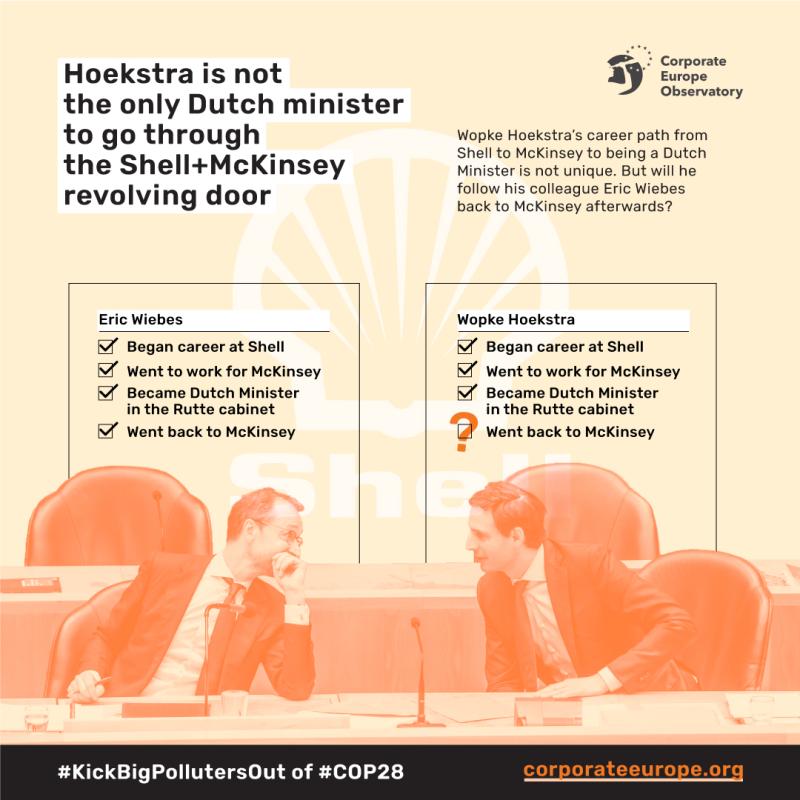

When considering this question, the revolving door between McKinsey, its fossil fuel clients and the Dutch government merits much greater scrutiny. The month after Hoekstra left McKinsey and took up the role of Dutch Finance Minister in October 2017, COP23 was held in Bonn. The Netherlands’ delegation at COP23 (as well as COP24 and 25) featured another newly appointed Dutch Minister: Eric Wiebes, Minister of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy. Like Hoekstra, Wiebes had worked for Shell early in his career, before moving to McKinsey.3 Wiebes and Hoekstra served together in the third Rutte cabinet, a coalition Dutch government in which Wiebes’ centre-right VVD and Hoekstra’s conservative CDA were the two largest parties. It ran from October 2017 to January 2021, when Wiebes left government.

Exactly one year later, Wiebes went back through the revolving door to become a partner at McKinsey Amsterdam, where he now specialises in decarbonisation and energy transition. A November 2023 McKinsey article co-authored by Wiebes promotes the fossil fuel industry’s long-promised but repeatedly failed techno-fix Carbon Capture, Usage and Storage (CCUS), claiming it is a means to “potentially unlock zero-emission horizons for technologies, such as (blue) hydrogen” made from fossil gas. When Eric Wiebes joined the firm in January 2022, McKinsey said that he would “not participate in any Dutch or European public sector work or interact with institutions or companies he dealt with during his time in government for a further period of 12 months.” This period ended in January 2023, long before his fellow alumnus of Shell, McKinsey and the Dutch government was appointed EU Climate Commissioner. Have they been in touch or will they be, and would it mean for Hoekstra’s agenda at COP28?

CEO asked Wiebes whether he had been in touch with his fellow ex-Minister about COP28, who replied that they had maintained “some level of irregular, informal contact”, and that while not assisting him or speaking to him on COP28 he has “no intention to avoid Hoekstra”. According to Wiebes, doing so would not “have posed a conflict of interest” but rather helped “prepare [him] for the COP with a good understanding of the most emitting processes.” However, when questioned about the potential conflict of interest of his own revolving door move, he commented that “McKinsey & Company has a policy to abstain from any advocacy or lobby advice.” Given the firm has been accused of advising the COP28 Presidency in the interest of its fossil fuel clients, and Wiebes himself agreed to not be in touch with his ex-colleagues for a year after returning to McKinsey, this appears a questionable response.

This kind of revolving door case is hardly unique. Gerrit Zalm, previously a Dutch minister, chaired the negotiations to form the Netherlands’ coalition government in 2017 whilst being paid by Shell (€117,000 that year) as non-executive director. An investigation by SOMO revealed that under Zalm’s supervision, a policy Shell had demanded for years – the elimination of the dividend tax – was included in the coalition agreement. And while Shell is not named in any of the Netherlands’ COP delegations analysed in the research for this article,4 the delegations did include Dutch officials that have subsequently gone through the revolving door to Shell. Shell’s Senior EU Affairs Manager Floris van Hövell, for example, was previously a Dutch diplomat who attended COP6 in 2000 and COP10 in 2004 as part of the Netherlands’ delegation. He was later seconded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to Shell as its Government Relations Advisor in 2012. The secondment ended in 2014, and van Hövell has been employed by Shell ever since.

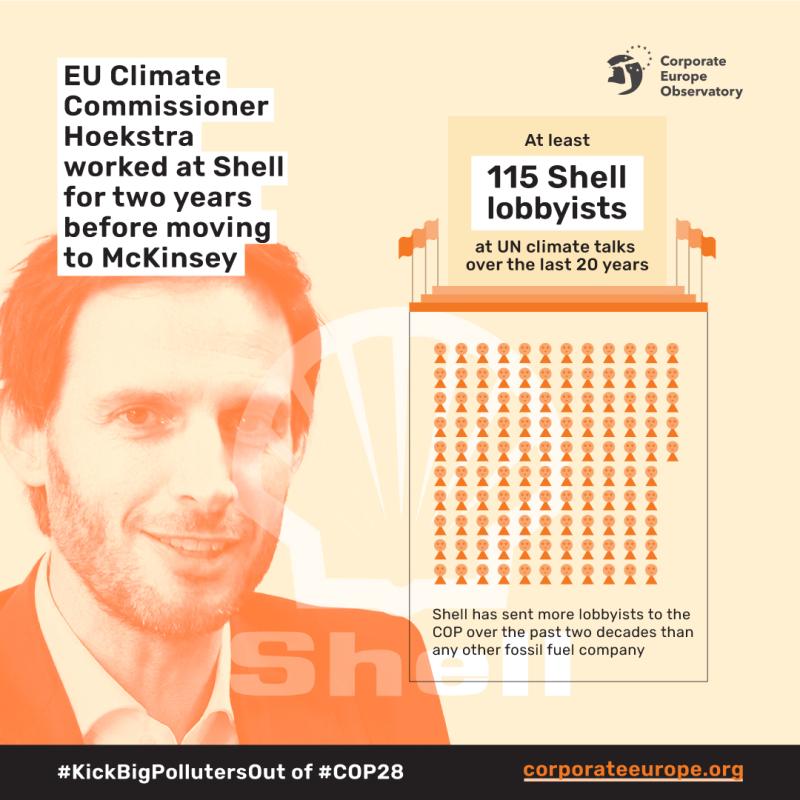

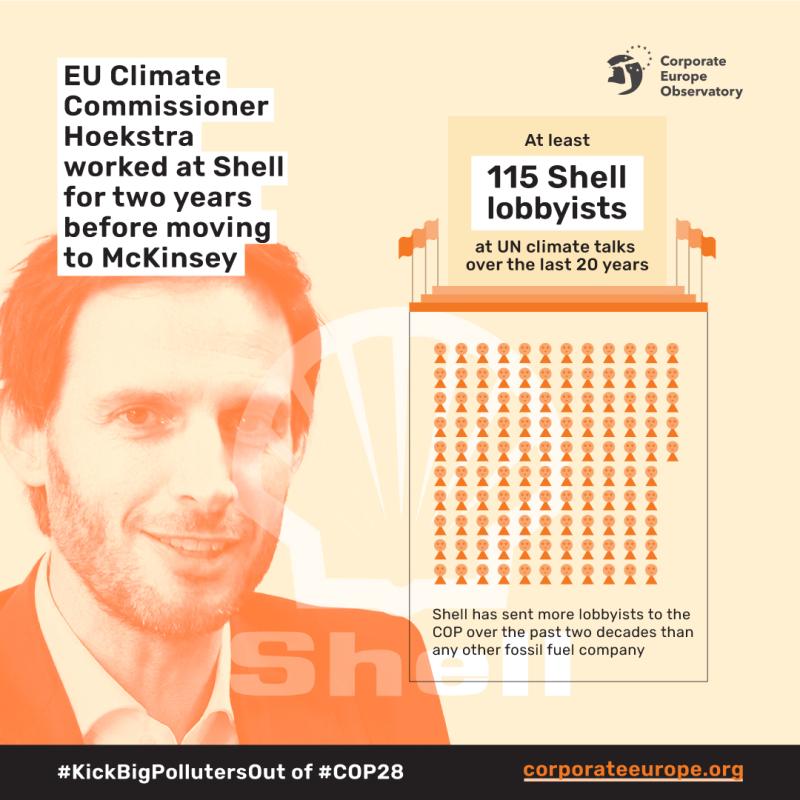

Shell – which Hoekstra worked for between 2004 and 2006 – has sent more representatives to climate COPs in the last 20 years than any other fossil fuel company – a total of 115 lobbyists. Most frequently, Shell lobbyists have attended COPs under the umbrella of the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA) – a group which has been instrumental in pushing carbon markets at the UN.

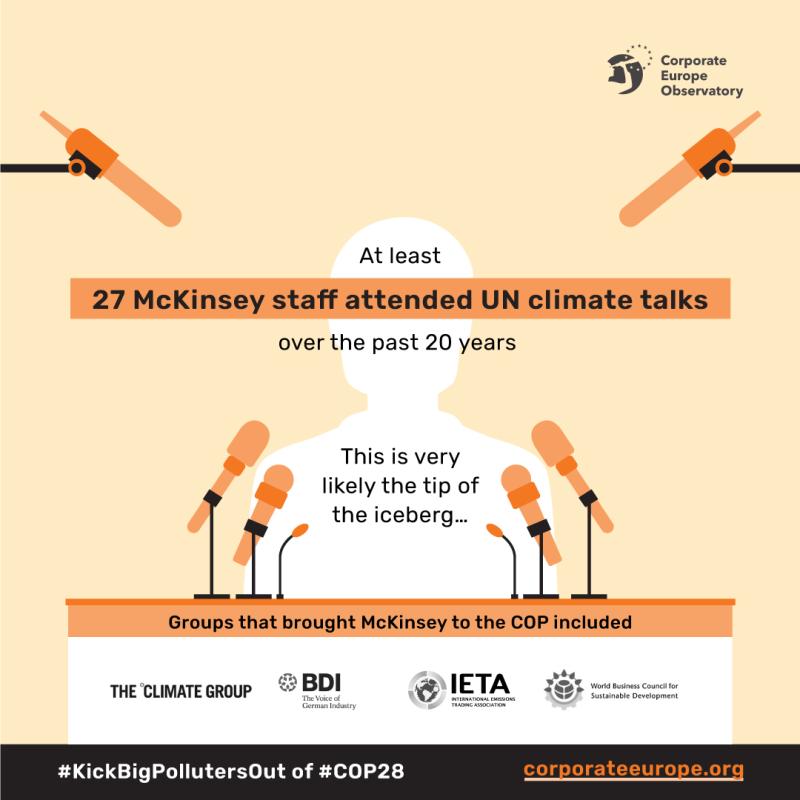

McKinsey itself has sent dozens of representatives to COPs over the past two decades, participating in a wide range of delegations. These include big polluter trade associations like IETA, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (of which McKinsey is a ‘knowledge partner’) and the Federation of German Industries (BDI), as well as private sector initiatives like The Climate Group. Controversially, four McKinsey staff members also appeared at COP15 in 2009 on the delegations of two rainforest nations (Papua New Guinea and Guyana). McKinsey’s ‘climate desk’ was advising them at the time on reducing emissions from deforestation. However, according to 2011 research by Greenpeace International into McKinsey’s proposals for both countries, “few if any of [the consultancy’s] resulting plans meet basic standards of accuracy, rigour, utility or ethical acceptability”. Moreover the research found that the firm’s recommendations “could actually result in an increase of deforestation and carbon emissions”, whilst also defending forest destruction by industrial interests to stimulate economic growth. Since COP15, ExxonMobil, another of McKinsey’s clients, has developed oil and gas projects in both Guyana and Papua New Guinea, to widespread local opposition.

These participation figures are likely only the tip of the iceberg, as declaring the ‘affiliation’ of a delegation member has been voluntary for most of the UN climate talks’ history. And at least one McKinsey partner listed under the “Oil & Gas” industries section on its website describes attending COP even though their name doesn’t appear in the respective participants lists. McKinsey partner Kassia Yanosek,5 who leads the firm’s “strategy work within the Oil & Gas Practice in the Americas”, wrote an ‘insight’ piece for McKinsey after COP27 in November 2022, describing how she “flew back from Sharm El Sheikh a few weeks ago, where I was part of McKinsey’s delegation to COP27”. And yet neither the provisional nor final list of participants at COP27 include the name ‘Kassia Yanosek’ (though the provisional list does include three other McKinsey representatives, in three different delegations).6 Despite this, Yanosek’s ‘insight’ piece name-drops false solutions ranging from hydrogen and CCS to carbon offsets, and her “key takeaways” from COP27 include the conclusion that we are “underinvesting in oil and gas relative to demand projections.” Yanosek was approached for comment and did not respond.

McKinsey’s perspective is in clear conflict with the EU’s commitment to meet the Paris Agreement’s goal to keep temperature rise below 1.5 degrees, a goal that the new Climate Commissioner has promised the European Parliament he will uphold.

Who will Hoekstra represent at COP28?

While groups around the world have rightly condemned the announcement of UAE oil executive Al Jaber as COP28 President, Hoekstra has flown under the radar, despite his pro-fossil fuel history and career (see box). The new Climate Commissioner told the European Parliament that he has “not worked for Shell or another oil company while at McKinsey”, but this doesn’t rule out gas or coal companies, fossil fuel-based electricity producers, or fossil fuel trade associations – let alone the plethora of other climate-wrecking industries. Before heading to COP28, Hoekstra should provide full transparency to the Parliament and the European public by publishing the list of clients he served during his years at McKinsey.

Yet regardless of who his clients were, there are a number of factors that make Hoekstra the ideal candidate, in the eyes of dirty energy giants like Shell and other McKinsey clients, to lead the EU at COP28. To begin with, there’s the length of service (more than a decade) and seniority of his role at McKinsey. Next, there is the fossil-friendly business model and culture of the company, which led to an internal revolt in 2021 over the firm’s continued work for the world’s biggest polluters. And last but not least, there is the global McKinsey network, whereby alumni remain plugged into each other – such as Hoekstra’s fellow former Minister, now (re)turned McKinsey partner, Eric Wiebes.

The key question is, given his own close relationship to big polluters, can we really expect Hoekstra to address their interference in the UN climate talks, and to promote the ambitious climate justice-oriented goals that EU citizens have been calling for? Positively, for the first time ever, participants at the talks will be required to disclose who they work for. This is an important first step towards transparency, but it still won’t prevent Shell lobbyists flooding the talks, or an oil executive being COP President.

That’s why the Kick Big Polluters Out coalition is campaigning for the UN to introduce an Accountability Framework to protect the talks from big polluter influence – similar to the conflict of interest measures taken by the World Health Organisation against the tobacco industry. The European Parliament has just called on the UN to do this in its COP28 Resolution, so Hoekstra should take note.

If the new Climate Commissioner wants to prove he represents the public interest rather than his past employers, he must not only reveal his client list and connections to McKinsey, but also ensure that the EU backs a robust conflict of interest framework at UN and EU level, to protect climate policy from the influence of big polluters. Otherwise he should expect a chilly reception on his return from Dubai, and not just because of the Brussels weather.

Footnotes

1. Walt Bogdanich and Michael Forsythe (2022). When McKinsey Comes to Town: The Hidden Influence of the World’s Most Powerful Consulting Firm. Doubleday

2. According to Walt Bogdanich and Michael Forsythe (2022) ibid.

3. Wiebes joined McKinsey & Company as a consultant in 1990, and from 1993 to 2004 worked as a consultant at OC&C Strategy Consultants, before embarking on a long political career that ended with his return to McKinsey in 2022.

4. Namely, COP9 to COP27.

5. Kassia Yanosek is also named as a participant at COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009, part of the delegation of the Bellona Foundation. According to Yanosek’s Linked-in profile, she worked at BP until 2008 (prior to which she was an energy advisor at the White House), and began working at McKinsey in 2012.

6. Namely, the United Arab Emirates, World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), and Vanke Foundation. However, the final list of participants for COP27 only includes the latter two.