The future according to Shell

Climate rhetoric and fossil fuel expansion

A little over a decade has passed since Shell plastered the landmark UN Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen with visions of its “new energy future”, sponsoring any climate-themed magazine supplement that was willing to take its money. “We’ll need to think the impossible is possible” was Shell’s message back then, even as studies showed that the company had the worst environmental record of any of the large oil multinationals.

On 19th May 2020 Shell will host its Annual General Meeting (AGM) at its headquarters in The Hague. The AGM will not be the most glamorous of its history, restricted to a bare legal minimum of two shareholders physically attending. Also, for the first time since the Second World War, Shell has cut its dividends (by two-thirds), as the pandemic has sent oil companies into crisis mode, with plummeting demand, unprecedented price crashes and a gloomy uncertainty over their future. This comes in addition to the growing tarnishing of Shell’s social license to operate, as mounting pressure on the streets demands strong action on the climate emergency, and several court cases challenge the company’s track record.

Shell is thus once again selling its supposed vision of a sustainable future, hoping to distract from the reality that the company bears a significant share of the responsibility for climate change and has a troubled human rights record.

As far back as 1984, Shell’s own research showed that it was responsible for 4 per cent of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions, and that it knew even then that these were causing climate change. Yet the company doubled down on oil and gas investment, and joined other oil companies in the Global Climate Coalition and American Petroleum Institute, two powerful lobby groups that spent millions promoting climate denialism. Dutch investigative journalists unveiled earlier this year that Shell had even paid a Dutch climate denier to mount a campaign against climate science. The company’s long record of human rights abuses and environmental destruction – especially in the Niger Delta – is also well documented.

By contrast, the future is a clean slate, free of reminders of the company’s unethical record. Shell increasingly talks of low-carbon scenarios, and last month it promised to become a net-zero emissions company by 2050. It sponsors an “eco-marathon” competition to develop the world’s most efficient car. It makes videos full of trees, electric vehicle charging points, and even glamourous social media influencers (#makethefuture). It promises support for “nature-based solutions”, and even says, loudly and repeatedly, that it “welcomes and supports the Paris Agreement and the ambition to limit the global rise in temperatures to well below two degrees Celsius.”

Shell has extremely deep pockets to bring that message not only to the public, but also to policy-makers. It spent over €4.5 million in 2019 alone on EU lobbying. And, along with the other lobby groups it is a member of, it has spent over €215 million SidenoteSee methodology box since 2010 on buying influence at the heart of the EU.

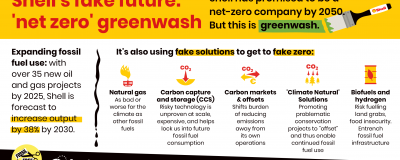

This is a textbook case of hypocrisy: Shell plans (or at least it did before being hit by the coronavirus crisis) to develop more than 35 new oil and gas projects by 2025, even though there is no plausible scenario for addressing climate change that allows for fossil fuel expansion on this scale.

But that is not it. When Shell talks about an “energy transition” and promises to be a “net-zero” company, this reflects not just greenwashing, but also the company’s attempts to mould the future in its own image. Shell’s envisioned future is one in which gas plays a significant, long-term role, and the lifespan of oil wells is extended through unfeasible and eye-wateringly expensive “carbon capture and storage” technology. Public policy should avoid regulation beyond setting a price on carbon, while international negotiations should ensure that remaining greenhouse gas emissions disappear through “net zero” accounting. Making the impossible possible, indeed.

Shell’s climate priorities: gas, carbon capture and carbon markets

Shell does not hide the fact that its “climate-related” priorities include burning gas for decades to come, backed up by a massive roll-out of costly and unproven “carbon capture” technology, and a system of carbon pricing that shifts the burden of reducing greenhouse gas emissions away from companies like itself. These three elements, backed up by the promise of “nature-based solutions”, form the vision of the rose-tinted future that Shell claims to dream of.

Glossary

Carbon capture and storage (CCS): With CCS, fossil fuels are still used, but instead of the carbon dioxide being released into the atmosphere, it is captured and stored underground or underwater. There are numerous practical problems associated with CCS, however, the biggest being that it is massively expensive – and would cost far more to implement than switching to renewable energy. There is thus little incentive for most investors to invest in long-term storage (existing CCS plants receive generous state subsidies). But there are considerable incentives for companies to use the captured CO2 for “fundamentally counterproductive purposes.” This Carbon Capture and Utilization (CCU) approach also facilitates Enhanced Oil Recovery, where carbon dioxide is pumped into depleted wells in order to extract more oil.

Carbon pricing A price is put on carbon by either taxing its use or creating an emissions trading system. Such policies aim to encourage companies to invest in cleaner production and to make carbon pollution more expensive, thus reducing demand. Carbon taxes on their own are highly regressive, hitting the poorest people hardest. Carbon trading sets up a system of “permits to pollute”, which allows big polluters (such as Shell) to follow business-as-usual while buying pollution permits generated elsewhere. These permits are often based on industrial efficiency savings that would have happened anyway, or “avoided deforestation” schemes that are not equivalent to cuts in fossil fuel carbon. Carbon trading is also linked to “offset” schemes that shift the burden of pollution reduction onto poorer people. Carbon pricing has not achieved its goal of encouraging cleaner investment, but it has been used to put a brake on regulations that would actually drive changes towards a cleaner economy.

Nature-based solutions

“Nature-based solutions” involve the restoration (or protection from destruction) of forests, mangrove swamps and other “carbon-storing” ecosystems. This is a new name for the old idea of promoting forestry and conservation projects as an “offset” for continued fossil fuel use. While burning fossil fuels is permanent, there is no certainty about the counting of carbon stored in forests, and considerable doubts about whether these “sinks” are permanent. Restricting climate change to 1.5 degrees will require forest restoration and preservation, as well as rapidly phasing out fossil fuels, rather than using one to cancel out the other. That is without mentioning the threats such solutions pose, as the search for “available” land to be restored will expand the already ongoing land grab from the forests to a much wider area of land under peasant cultivation.

Gas, gas and more gas

Above all, Shell’s “climate” vision is one in which gas continues to play a central role in the energy system. It promotes gas as a “bridge” fuel that can help to reduce reliance on coal and achieve immediate cuts to greenhouse gas emissions.

Shell has also encouraged the EU to see gas as the bridge away from coal and towards a “low carbon” energy system, rather than renewables: as the company wrote to former Commission President Barroso in 2014: “Gas is good for Europe, and Europe is good at gas”. Since then Shell has redoubled its lobbying efforts to put gas at the heart of EU energy policy, and promotes its continued use in the many important policies currently being drafted, including the European Green Deal, the upcoming gas market regulation and the TransEuropean Networks for Energy (TEN-E).

But burning more gas would take the world far beyond safe climate limits, and lock in a reliance on expensive fossil fuel infrastructure for decades to come.

Carbon Capture and Storage/Utilization

In reality, Shell’s plans are as fanciful as they are dangerous. Its global vision is outlined in the ethereally named “Sky” scenario. “In 2070, Sky achieves net-zero emissions in the energy system, but the use of fossil fuels is far from over”, explains Shell’s Chief Climate Change Advisor David Hone. The circle in this vision is magically squared by assuming that 10,000 CCS facilities will be in operation by 2070. Shell has already used this scenario to lobby the European Commission to promote the “large scale deployment of CCS projects”, as a means to reach “Net Zero Emissions”.

At present, despite considerable hype and government subsidies, there are just 51 CCS plants globally, many of which are small-scale. The biggest impediment to CCS is that it is “wildly expensive” while, at the same time, renewable energy is rapidly falling in cost. As a result, CCS either relies on state subsidies, or on companies finding environmentally harmful ways to “utilize” the CO2.

Shell’s own investments in CCS follow this pattern, as the company unwittingly admits. The Quest project in Alberta, Canada, is the company’s flagship CCS project, but it “has benefited from significant government funding”, notes Shell Canada President Michael Crothers. He further states that industry is looking to a “self-funded” future in which it can generate revenues from CO2.

Carbon capture is also a byword for postponing emissions reductions, as was seen with the Gorgon gas project in Australia - a Chevron CCS project in which Shell holds a 25 per cent stake. The state-funded project was subject to long delays, with local groups claiming it was “deliberately mismanaged” to help the companies to avoid meeting environmental regulations. Gorgon plans to capture just 40 per cent of the emissions from the massive Western Australia gas plant, which only originally won approval on the grounds that it would “sequester” emissions.

Carbon Markets

Shell has consistently supported carbon emissions trading and, in certain jurisdictions, carbon taxes (see “glossary”). Although the company trumpets this support as evidence of its commitment to climate action, the main reason for this enthusiasm is that carbon pricing benefits the company’s core gas business. Firstly by helping gas to out-compete coal (in the electricity generation sector), and secondly by undermining the case for other regulations, targets or renewable energy subsidies.

Shell’s support for carbon pricing should not be confused with climate ambition. Even in cases where it argued for a higher price in the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), its goal was for gas to out-compete coal, and to avoid renewable energy becoming the norm. Indeed, when the EU threatened to make Shell pay for pollution permits in 2008, the company threatened to quit Europe altogether. Shell was also one of the lead actors which successfully undermined the EU 2030 renewable energy targets in 2014, when the EU decided that the 27% target for renewables in the energy mix would not be binding on individual member states.

To this day, Shell continues to argue that the impacts of carbon pricing should be tempered by rebates for industry. Outside the EU, Shell has lobbied against efforts to introduce more ambitious targets in California’s cap and trade scheme, and opposed a Washington state carbon tax proposal.

Another reason that Shell supported carbon pricing relates to its support for CCS, which it argues should receive subsidies paid for by the auction of pollution permits. Even Cefic (the EU chemicals industry lobby, of which Shell is a member), admits that the company has a “vested interest” here, because “they have invested a lot of money into CCS.”

Nature-based solutions

Shell’s latest climate concept involves promoting “nature-based solutions”, focusing on the “protection and restoration of natural ecosystems such as forests, grasslands and wetlands.” This is a textbook act of “greenwashing” – producing videos, brochures and other PR materials that feature thriving woodlands in order to mask the dirty reality of Shell’s core activity.

“Nature-based solutions” is a new name for an old idea: promoting forestry (and other land use) projects as an “offset” for continued fossil fuel use. The carbon absorbed by forests is counted and “credits” are then issued for supposed “emissions savings”, which can then be used by Shell to justify its continued extraction, refining and sale of oil and gas. The company promised to set aside US$100 million a year to invest in natural ecosystem projects by 2021, a significant sum in the context of a forest carbon market that has failed to take off, but a drop in the ocean compared to the overall size of Shell’s business. Moreover it is also a very risky business for the many local communities that can find themselves displaced as a result of land grabs for such lucrative offsetting projects.

The credibility of Shell’s investment in ecosystems also seems to be somewhat undermined by the company’s bio-ethanol production operations in Brazil, where it owns a 50 per cent stake in Raízen, a multi-billion dollar company that is one of the largest players in an industry that has driven wide scale deforestation in the Amazon.

These are also the final pieces of the jigsaw, that allow Shell to claim it supports the Paris Agreement. Shell’s investment in offsets allow it to claim that its “net” emissions will reduce to zero, even as it continues to extract oil and gas. The reality is that burning fossil fuels and storing carbon in trees and soil cannot be compared – and that any hope of restricting climate change to 1.5 degrees requires real forest restoration and preservation in addition to rapidly phasing out fossil fuels.

Shell Scenarios: Pie in the Sky

Shell has been publishing energy models since the 1970s. It has increasingly turned its modelling into a PR exercise designed to convince the world that it is sustainable. The company’s most recent scenarios have been given natural names that wouldn't sound out of place in a yoga studio: “Mountains”, “Ocean” and “Sky”! “Mountains” envisages a world where gas is the “backbone” of global energy systems, while “Oceans” envisages greater reliance on oil and coal, eventually eclipsed by solar power, but too slowly to avoid overshooting the 2°C temperature goal.

Against this backdrop, Shell has developed the “Sky scenario” as “a technically possible, but challenging pathway for society to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement.” “Sky” is not a prediction or a set of policy proposals, but more of an ideal-type that adheres to the projections of those parts of the company that work on “sustainability” (rather than the much larger business units whose task is simply to exploit ever more oil and gas). It envisages “net-zero emissions” by 2070.The scenario rather ambitiously assumes the global adoption of carbon-pricing mechanisms, the building of 10,000 CCS facilities (there are currently just over 50), a step-change in energy efficiency, and significant reforestation.

Shell’s scenarios give insights into how it sees the “risks and opportunities” of a world transitioning to “lower-carbon energy.” However, they are not a reliable guide to what the company is doing or plans to do. Shell’s energy scenarios should ultimately be seen as part of a broader greenwashing effort to promote the company as a climate expert that provides “energy ideas”, and a PR operation to suggest it is a forward-looking, sustainable company.

How Shell is trying to make its dystopia come true:

Investing in a fossil fuel future

“Despite what a lot of activists say, it is entirely legitimate to invest in oil and gas because the world demands it” - Ben van Beurden, Shell CEO.

The extent of Shell’s ongoing commitment to exploiting oil and gas tends to be hidden by the company’s PR efforts, but it is crystal clear in its investment portfolio. Shell is Europe’s biggest oil and gas company, and intends to remain so. Before the pandemic exploded, it was planning more than 35 new oil and gas projects by 2025. Shell has plans to diversify its business eventually – most oil companies do – but that future will come more slowly than the company’s shiny “sustainability” brochures imply.

Shell’s “growth priorities” in the coming years are in deep-water oil exploration and the chemicals sector. Half of the 24 “major projects” in its investment profile are deep water oil and gas projects (in the Gulf of Mexico, Brazil, Malaysia, Nigeria and Norway), which it says have “significant growth potential.” The remainder of its major projects under development include conventional (offshore) oil and gas, petrochemicals, gas-to-power and LNG plants.

These investments could hardly be further removed from ongoing efforts to avert climate chaos, and the company admits that it will continue to invest significantly in new oil and gas capacity for at least the next two decades. Shell intends to develop “New Energies” further in the future, but it is dipping its toes into the water rather than diving right in. Before the coronavirus crisis, just US$1bn-$2bn of Shell’s annual $25bn-$30bn capital expenditure was for “low-carbon” projects, and this seems to only go lower now.

Moreover, Shell’s New Energies investments are not guaranteed to be clean. The company is as heavily invested in biofuels and hydrogen-powered cars as it is in wind power and electric vehicle charging. The “Shell Ventures” division, which invests in new technologies, has an equal interest in deepwater oil extraction technologies and in next generation solar panels. Shell also sees “longer term” opportunities from investment in shale gas in North America and Argentina.

Before the yet unknown impact of the coronavirus crisis, Shell was forecast to increase output by 38% by 2030, increasing its crude oil production by more than half and its gas production by over a quarter. If you follow the money rather than the company’s words, it is clear that Shell is aiming to continue profiting from oil and gas production for as long as possible, as well as dedicating significant resources to “extreme” fossil fuels like deep sea oil drilling (Shell operates the deepest offshore oil and gas project in the world) and fracking for gas.

Shell’s lobby millions

Shell spends millions of dollars annually lobbying governments and international institutions around the world. In the EU alone, Shell has the third largest individual company spend on lobbying in Brussels (after Google and Microsoft) - it spent over €4.5 million in 2019. It also ranks as the twenty-second largest lobbyist overall, coming after a number of industry federations and PR companies. SidenoteShell is counted as 22nd rather than 23rd because it is likely that the lobby spend for UGT Spain is incorrect Shell is on the Executive Board of CEFIC, Brussels’ largest lobbyist, which has a €10.5million annual spend.

Since 2010, Shell, and the ten lobby groups SidenoteBusiness Europe, the European Roundtable for Industry (ERT), European Chemical Industry Council (Cefic), EUROGAS, European Energy Forum (EEF), FuelsEurope, Hydrogen Europe, International Emissions Trading Association (IETA), International Association of Oil & Gas Producers (IOGP), ETIP ZEP (ZEP) it declares itself to be a member of in the EU’s Transparency Register, have spent over €215 million buying influence at the heart of the EU. In addition to the money, Shell enjoys privileged access to EU decision makers. SidenoteThe exact figure is €215,317,227 million

Since November 2104 (when it became obligatory for high-level officials of the European Commission to register their meetings with lobbyists) the company has had 67 meetings with the Commission’s elite. If we count the number of meetings that not only Shell, but also the lobby groups it is a member of had, the number rises to 569 - almost two per week! This is hardly surprising given the army of lobbyists declared by Shell and its allies - 175!

It is the same in the US, where a study of big oil and gas found that these companies had spent over US$400 million on lobbying between 2010 and 2016. Shell is a member of all of the major US lobby groups, and while much has been made of its plan to withdraw from the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers association, it remains part of the far more influential American Petroleum Institute and US Chamber of Commerce. These groups have routinely lobbied against climate regulations.

Conclusion: a fossil-free future

Strip away the green brochures, the techno-optimism of carbon plucked directly from the air at a massive scale, and the heartfelt commitment to letting the market resolve a climate crisis that it was key to creating, and Shell’s future vision remains one where oil and gas are burned far beyond planetary boundaries.

Shell’s climate rhetoric is designed to signal that it is the cleanest of the big oil companies. Even if that were true – it is like claiming to make the healthiest cigarettes. In the end, they still kill you.

The tobacco analogy is far from arbitrary. In 2003, the World Health Organization acted to protect policy-making from the influence of the tobacco industry (via article 5.3 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control). It is high time for the world to adopt the same approach to the fossil fuel industry. We must kick Shell and other big polluters out of the conference halls where climate policy is negotiated, and out of the EU institutions and national capitals. This would finally clear one major obstacle to taking action commensurate with the scale of the climate crisis. We need Fossil Free Politics before it’s too late!

Methodology and disclaimer

This content is the sole responsibility of Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO) and should not be regarded as reflecting the position of any of the more than 200 organisations supporting the call for fossil-free politics, including the founders.

Transparency Register data on LobbyFacts – which shows all previous versions of an organisation’s lobby register entry – was used to calculate the historical spending figures. (ec.europa.eu/transparencyregister and lobbyfacts.eu - accessed on 14th May 2020). Where the spending figure for a particular year was changed/updated, the most recent figure was used. Where a threshold lobby expenditure was declared, the upper figure was used. ETIP ZEP has had two entries in the Transparency Register, one now expired (“ETP ZEP (ZEP)”) and one currently active (“ETIP ZEP (ZEP)”) – lobby spending figures from both the expired and the currently active entries are used to cover all relevant spending declarations for the years 2012-2018 (only ones declared).

The lobby spending figures used in these infographics are in fact only the tip of the iceberg. These figures do not touch on the millions being spent on misleading climate-related branding or advertising. What’s more, these figures are based only on those declared in the EU’s voluntary Transparency Register over the period from 2010 onwards - a period which has been plagued by absences, omissions and unrealistically low declarations. Not all organisation joined the register from the beginning, in spite of their lobbying.

The data on high level lobby meetings is pulled from the European Commission’s public record as compiled by Integrity Watch (integritywatch.eu - accessed on 14th May 2020). Since November 2014, European Commissioners, their cabinets and the Director-General of the European Commission cannot meet lobbyists that are not registered in the Transparency Register. They are also obliged to publicly declare those meetings on the European Commission’s website.