Thinking allowed?

How think tanks facilitate corporate lobbying

Think tanks work all around the institutions of the European Union but how they work and who they work with is often less clear. Our new report offers a closer look at these supposedly impartial hubs of expertise and highlights how the think-tank status has become a convenient vehicle for corporate lobbying activities.

“How do you change the world? Well, there are the obvious routes, such as seizing power, being monstrously rich or slogging through the electoral process. And there are short-cuts, such as terrorism or forming a think tank.”

Steve Waters, 2004 (The Guardian)1

As a company, to guarantee the continuity of your profit-making, certain laws and policies need to be in your favour. To make sure this happens you need to do some convincing at high levels. Of course, sometimes what you want runs counter to the demands of civil society and public interest groups. So to avoid provoking public resistance, you have to advance your ideas in a subtle way, or – even better – through channels other than your own. One tried and tested such channel is to create a think tank, or become a member of, finance and/or make use of the services provided by one that 'thinks about' your topic of interest. Through the production of 'objective' research, disseminating its results through the organisation of (high level) events and various media channels, think tanks spoon-feed policy-makers with arguments supporting your cause. On top of that they create the illusion that they – and their members – are objective and open for debate. Doesn't that sound fantastic?

Many major corporations who have an interest in European policies have understood that this is the way to go. Some corporate interests have even set up their own think tanks, dedicated to a certain subject so as to foster an “objective debate” and 'correct' criticisms in the mainstream media; others become members of or make donations to think-tanks making sure that decision-makers “make informed decisions”, providing a “forum for discussion among all stakeholders in the European policy process”. Among their ranks we often find (ex-)MEPs and/or former commissioners; a very worthy asset in the world of lobbying, as research has proven.https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/documents/pe_03_11_vidal.pdf. This research from the US shows the value added of a lobbyist when he/she has personal connections with elected representatives." href="#footnote2_7pkln9j">2

In 2004, Steve Waters in The Guardian wrote: “Yet as think tanks fight for airspace and for a chunk of the ideological spectrum, they increasingly resemble the corporations and government agencies they increasingly serve.”3 Today we know that many think tanks are backed by corporate sponsors, by companies which pay membership fees, and/or by other partners co-organizing events or co-writing publications. Very occasionally corporate interests club together to set up a think tank, thereby camouflaging their interests.

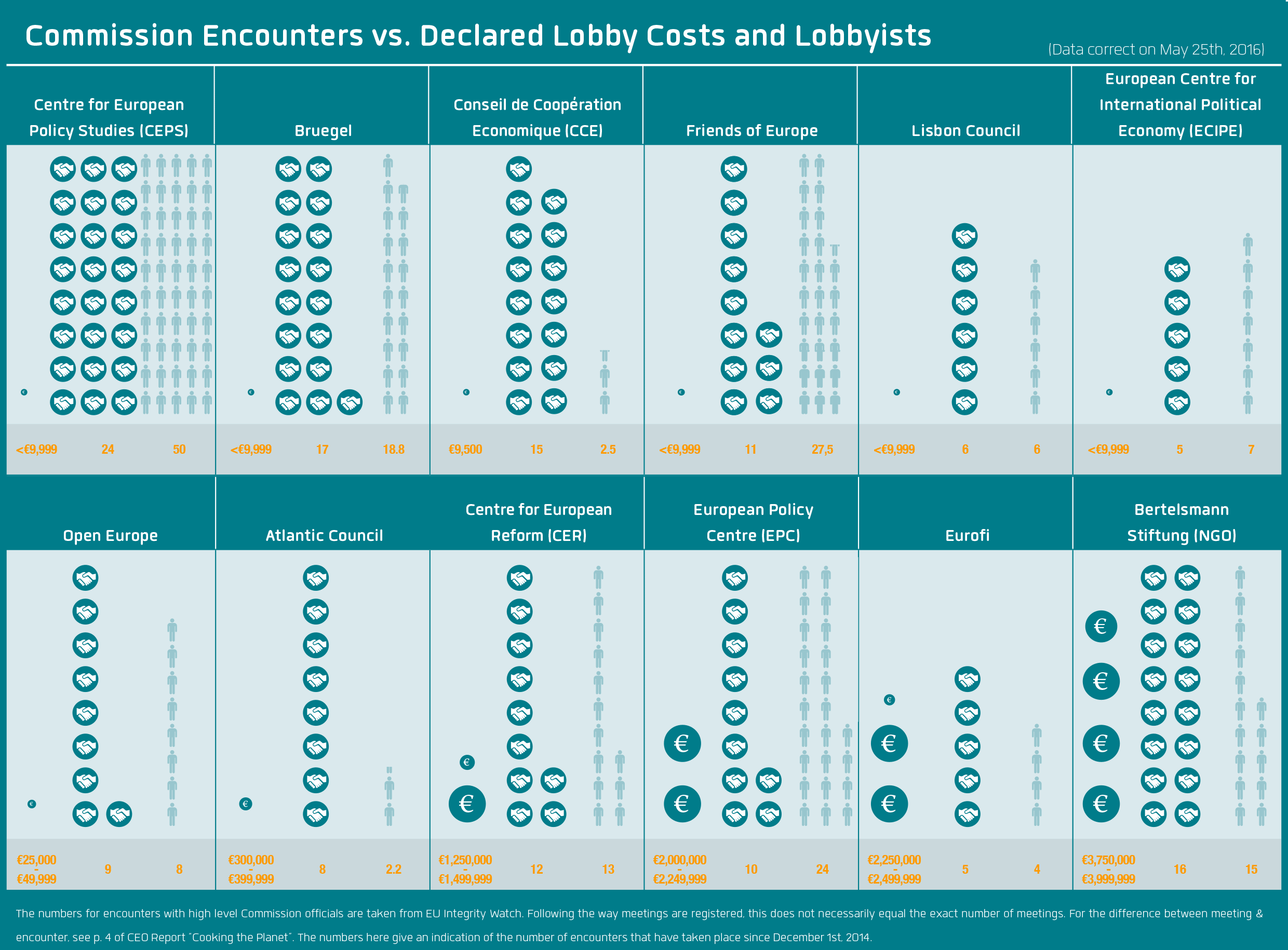

Groups carrying out activities “with the objective of influencing the policy formulation and decision-making process of the European institutions” are expected to register in the European Union's Transparency Register – a list of groups and organisations with which the European Parliament and the European Commission interact, among other things providing information on their interests and budgets. This definition clearly includes think tanks, as agenda-setting and influencing the debate is their basic mission. However, for many years, a big share of think tanks have refused to register.4 Today most have joined, yet a few remain suspiciously absent. Others don't seem to take the Register very seriously, for example reporting lobby costs so low that the figure cannot be reconciled with the number of lobbyists declared or the frequent meetings held with high-level Commission staff.

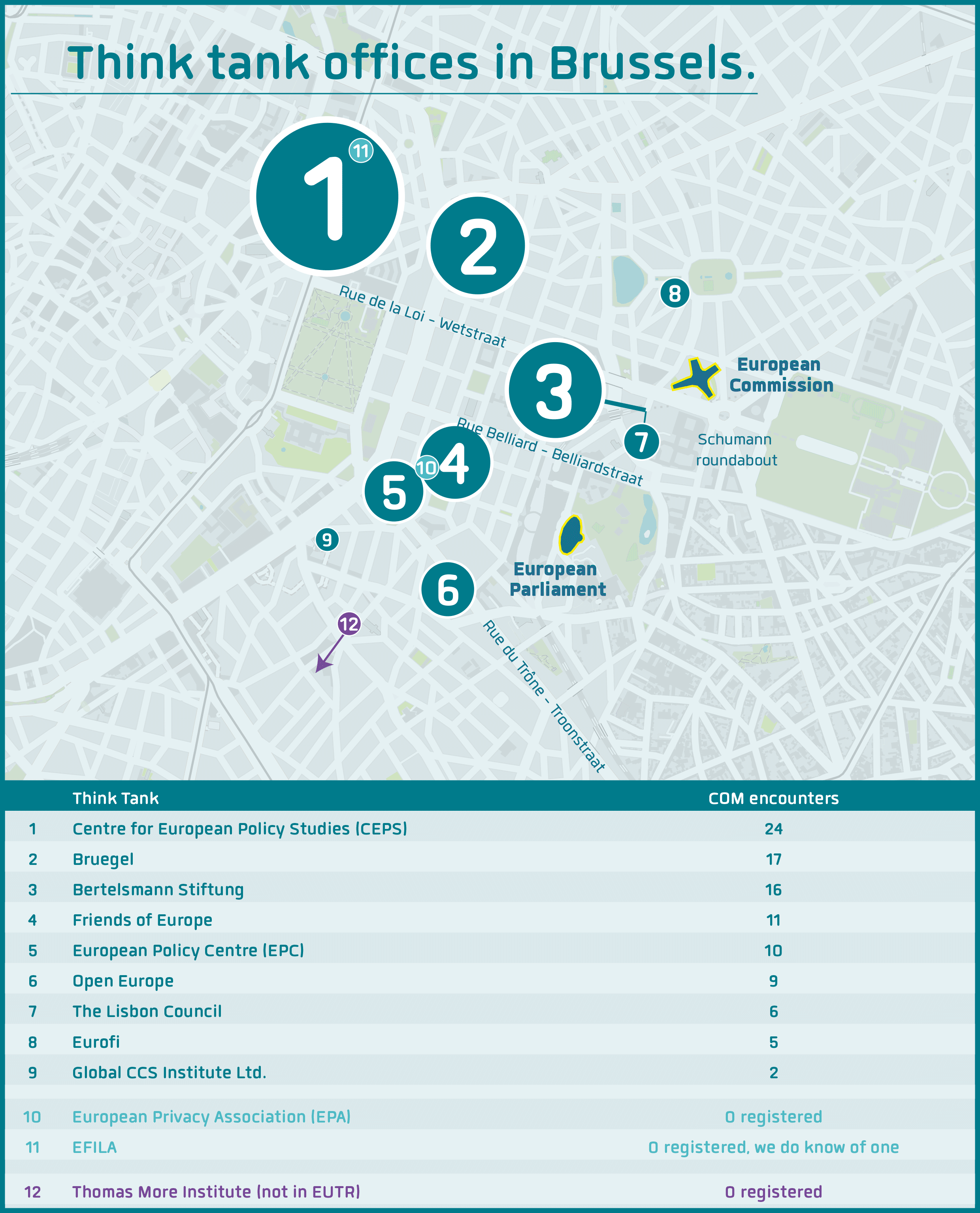

According to Transparency International's Integrity Watch,5 between between December 2014 and March 2016, 385 encounters between think tanks and Commission officials were listed. Interestingly, more than one third of these encounters involved only eight organisations,6 ie less than two per cent of the total number of think tanks in the Register (462). More than half of the encounters with high-level Commissioners involved only 20 think tanks. In total, think tanks have had more (385) listed encounters with high level Commission officials than professional consultancies (377) and trade unions (363). Only NGOs, trade associations, and companies have had more encounters.

On their websites and in their Register entries, they may declare themselves “independent” or “not lobbying”, but it is clear that think tanks do sometimes take a certain ideological track that benefits the business community, at the expense of their independence. A couple of them have even more direct links to specific corporate interests. While some are more transparent about it than others, either way corporate backing raises concerns about some think tanks' agenda and ambitions.

I think (tank), therefore I am

Registering in the EU's Transparency Register can be complex. Categories are not very well defined by the guidelines, and registering under several categories is not allowed. The section where think tanks belong, for example, is described as follows: “Specialised think tanks and research institutions dealing with the activities and policies of the European Union”. No more, no less. This mysterious and catch-all category makes it very easy for a wide range of organisations to register under it. Even though the guidelines try to steer the organisations toward the right category by stating “[i]f you are in any doubt, the decisive factor should be what you do, not your legal status”, several still seem to make the mistake of registering in a category where they clearly don't belong.

Am I think tank or am I not, you told me once but I forgotCEO has discovered an interesting change in the Register's guidelines between 2012 and 2014: In 2012, the Guidelines stated the following:

It will become clear that many of the think tanks listed in this article – some of which have registered before 2012 – do not correspond to this definition. By 2014, the definition referring to think tanks had been updated to:

A very vague definition and no mention of profit-making. Why is this the case? Was this pushed by certain interest groups, accidentally left out, or left out because in practice 'think tanks' were not following these guidelines? Maybe the case of the European Privacy Association (EPA) could suggest an answer? In 2013, CEO filed a complaint to the Register secretariat as EPA, then registered as a think tank, failed to disclose its members and funders. Thereupon EPA updated its entry, disclosing members such as Google, Yahoo, and Microsoft, and funders like Facebook. This indicated that EPA was not there to protect privacy, but rather to weaken governmental decisions with this objective. Following CEO's complaint, EPA also changed its category to the one where it belongs: trade association. Last year, however, it stubbornly recategorized itself into think tank – again. Was this made possible by this altered definition? Its most recent Register entry states it “currently does not have any corporate supporters” and that “five individuals currently serve EPA. None of them are employees of the Association”. The ones whose names we know (because they are mentioned in the Register) are, nevertheless, members of corporate institutions, with interest in privacy policy-making: Florian Damas, Director at Nokia, and Paolo Balboni “top tier European ICT, Privacy & Data Protection Lawyer”, serving multinational companies. This means that while the EPA's link to Big Data corporations continue, it is by no means obvious from the Register. |

Corporate interests masquerading as think tanks

When browsing through the organisations registered as think tanks in the Transparency Register, some names of groups with unambiguous interests pop up. To give the impression of neutrality and openness to debate, calling yourself a think tank could be a good strategy. The reality, however, shows the limits of this supposed neutrality.

Bank lobby group Eurofi, for example, besides claiming to be a think tank, states on its website that it's a “platform for exchanges between the financial services industry and the EU and international public authorities”. One of its objectives, it says, is to “open the way to legislative or industry-driven solutions”. To reach this goal, Eurofi brings together diverse financial industry players and – it declares – acts as “a neutral go-between”, connecting them with public authorities. This supposedly 'neutral' link is very much in evidence. Eurofi's President is Jacques de Larosière, advisor to BNP Paribas and – in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis – he chaired Barroso's High Level Group of financial “wise men”, a group of mainly financial industry insiders to advise the EU on how to respond to the crisis. The famous saying, “we cannot solve our problems with the same kind of thinking we used to create them” was certainly disregarded in this case.

Eurofi offers various privileges to its members from the Big Finance family – companies like BNP Paribas, ING, BBVA, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, etc – including: straight access to decision-makers, through meetings on specific regulatory topics or through communicating proposals to decision-makers; and the possibility of sponsoring one of the annual events, “providing specific visibility and networking opportunities.” The annual Eurofi Financial Forum is referred to by the City of London Corporation as “a key event in the EU financial services calender… which brings together financial services industry representatives with EU policy makers.” Eurofi members are promised active involvement, both in the preparation phase and as speakers.

In its Transparency Register entry Eurofi declares between €2,250,000 and €2,499,999 costs and four full time equivalent staff related to activities covered by the Register. No European Parliament accreditation passes are registered under Eurofi's name.7 Four meetings8 with Commission officials are registered since December 2014, all on financial matters.9

The Conseil de Coopération Économique (CCE) is also a peculiar kind of think tank. The least we can expect from a think tank is to share its ideas with a wider public. For CCE this is quite challenging, as their website is nowhere to be found. In its description10 in the Register, it describes itself as an “advisory board”, established in 2002 to support the Spanish, French, Italian, and Portuguese governments in their preparations for the European Councils and bilateral summits concerning sectors of the economy. Absent from the internet, what we do know about this group of actors is that its current President is Andrea Canino, active in the financial industry and adviser to various Italian prime ministers.11 In February this year, he was received by Commissioner Moedas.12 In 2013, a CCE delegation was received by then Commission President Barroso.13 The delegation then consisted of representatives from big companies from Greece, Spain, France, Italy, and Portugal.14 From what can be seen on Integrity Watch, the CCE has had at least 12 meetings15 with Commission officials since the end of 2014.

In November last year, ALTER-EU published an article on the results of a series of complaints to the EU lobby Register secretariat. Part of the complaint was about the CCE's suspiciously low reported lobby costs (<€9,999). Following the complaint, CCE changed its entry, recategorizing itself from the NGO to the think tank category and further lowering its stated lobby costs (now stating €9500).16 It declares 2.5 full time equivalent lobbyists and no European Parliament passes.17

Through statements made in the Register, such as “members are forbidden to promote specific interests of their company through the CCE”, or stating that their work comes down to “reflection and exchange on European level” and not “lobbying or interest representation”, they continue to insist that their activities are 'lobby free'. CEO’s concern is that the CCE secures a significant level of access to senior policy-makers and is likely to be promoting an agenda which suits the broad interests of the corporate sector.

The Global Carbon Capture and Storage Institute (Global CCS Institute) also registered itself as a think tank under the Register. As can be guessed from its name, the GCCSI advocates for Carbon Capture and Storage technology, which in theory means capturing CO2 released into the air – eg by a fossil fuel power plant – and storing it underground. However, the efficiency of this technology remains unproven and it cannot yet be applied on a large scale. Moreover, it involves major environmental risks (for example leakage) and is extremely expensive. Yet, even though more efficient alternatives are already accessible, the fossil fuel industry continues to use the idea of this technology as an argument to continue their extract-and-burn business as usual.18

One of the Institute's aims is to advance the interests of its members: “focus on the needs of Members is central to the mission of the Institute. Since its inception, the Institute’s output has been focused on ensuring CCS continues to be an integral component of a low carbon future.”19 Members include companies such as Arch Coal Inc., BHP Billiton Ltd, Brazilian Coal Association, ENGIE, Shell, World Coal Association, all of whom have clear interests not to 'leave the coal in the hole', but rather to allow it to come out first, and then (maybe) put it back in. And this despite the overwhelming scientific evidence about the need to leave coal reserves untouched.20

Members also include other fossil fuel companies, and several of the Institute's publications are co-written by companies with a large stake in being able to continue to emit carbon dioxide. The publication “CCS: A China Perspective”, for example, was in collaboration with Yanchang Petroleum. And a Shell CCS project case study is presented in “The Quest for Less CO2”. Pushing for and supporting technologies like these leads to and strengthens a fossil fuel lock-in, making our energy systems dependent on fossil fuels, rather than getting rid of them. This does not contribute to reducing emissions nor does it avert climate change, rather the opposite.

The Institute's Transparency Register entry declares a total budget for 2014-2015 of €12,999,700. Of this total amount €12,210,800 came from public financing. Besides receiving €274,000 from DG Energy, about 98 per cent21 of this public funding came from “national sources”, which seems to be the Australian Government.22 However, as the Institute does not proactively publish its accounts, it is hard to say where exactly these funds are coming from. This is an important issue, as information on funding sources is key when it comes to external scrutiny of an organisation's intent.

Another €788,900 of its declared funding came from member contributions. Interestingly, out of the ten public authorities listed among its members, two are Canadian: the Government of Alberta and the Government of Saskatchewan. These are the regions where the great majority of Canada's oil reserves are located in the form of the highly controversial tar sands.23 An example of this controversy was the 2000-miles long Keystone XL pipeline that would transport unprocessed tar sands to refineries on the Gulf Coast. It gathered massive public protests and was ultimately rejected by the Obama administration.24

On the Transparency Register, for 2014/2015 the GCCSI reported €400,000-€499,999 lobby costs and eight full time equivalent lobbyists. We can see seven people from the institute hold a European Parliament pass for 2015/2016.

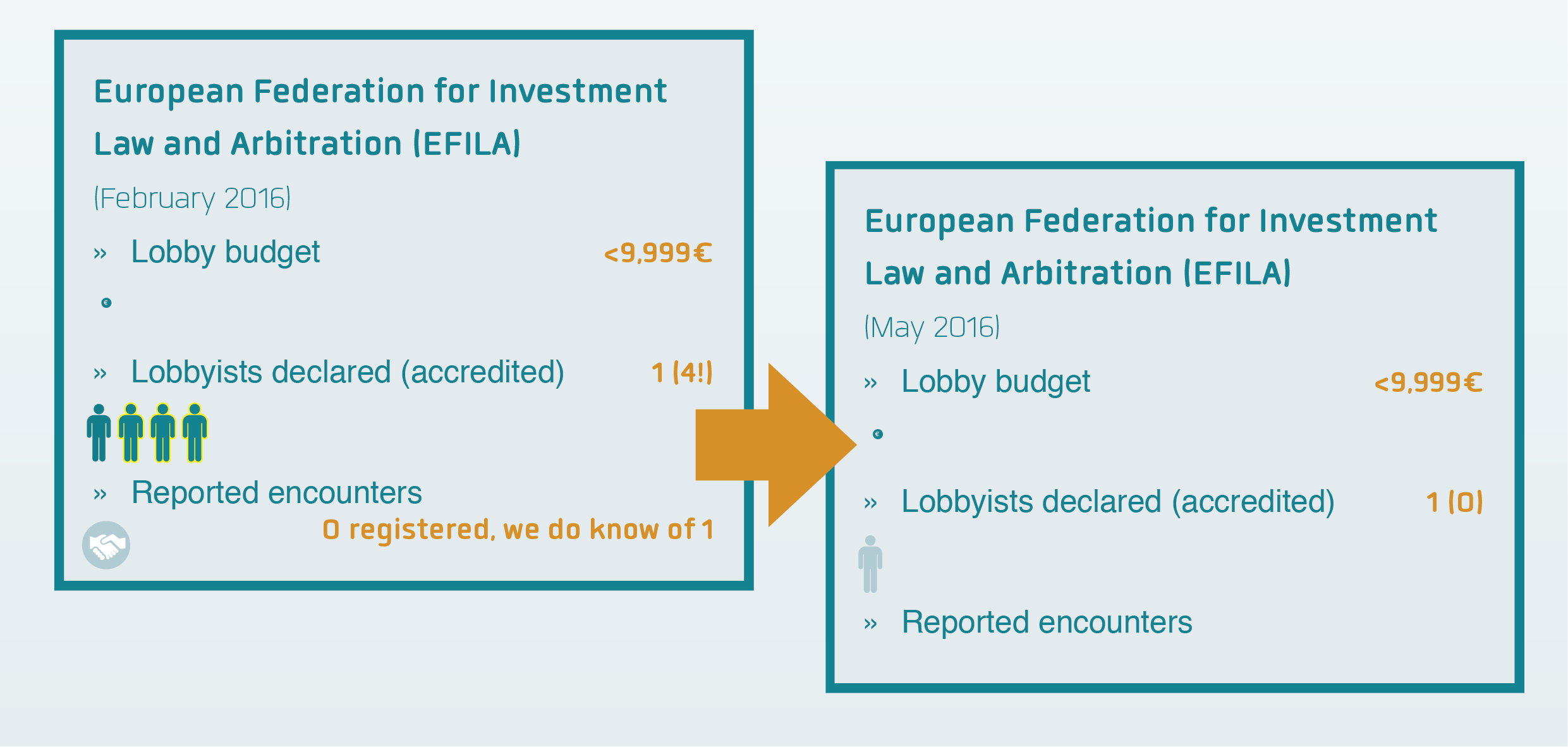

Another group misleadingly categorized as a think tank is the European Federation for Investment Law and Arbitration (EFILA). Strategically launched in January 2015, when public awareness of and civil society resistance against Investor-State Dispute Settlement25 was soaring (a historically high level of citizen submissions were received in a public consultation), this lobby group aims to be the “main voice of users of investment arbitration at EU level.”

EFILA's founder is Nikos Lavranos – former advisor to the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who led several bilateral investment negotiations of the Netherlands with third countries, helping to write treaties that are generally considered some of the most investor-friendly in Europe. EFILA's members include law firms representing some of Europe's biggest companies.26 Out of EFILA’s ten member companies, seven are not registered in the EU lobby Register.27 Together they wish to protect the inclusion of ISDS in the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Agreement (TTIP), the trade deal between the EU and the USA that is currently being negotiated. This is not surprising as corporate law firms would have the most to gain if this deal goes through. As would companies like multinationals Shell (oil and gas) and Sanofi (pharmaceutical), representatives of which we can find on EFILA's Advisory Board.

Even though not listed on Integrity Watch, we know EFILA has had at least one meeting with the Commission to discuss ISDS, in October 2014. On the Register, it declares less than €9,999 lobby costs and one full time equivalent lobbyist for 2015. Interestingly, in 2014, EFILA went from declaring up to €50,000 lobby costs, 23 lobbyists and no Parliament passes, to disclosing only one full time equivalent lobbyist, while having four accredited employees28.

Activities covered by the Register include "lobbying, interest representation and advocacy. It covers all activities designed to influence - directly or indirectly - policymaking, policy implementation and decision-making in the EU institutions".29 In the case of EFILA, we believe that less than €9,999 is an unrealistically low lobby spend. When asking EFILA to explain why it declares its annual costs related to activities covered by the Register to be below €9,999, we received no reply.

(Read more on EFILA's stake in investment arbitration here.)

Thinking pays off

Granted, some think tanks do show a commitment to transparency by publishing a list of funders and/or members on their websites. For example the European Policy Centre (EPC), the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) and the Atlantic Council have clear website sections on what membership entails and who their members are. However, while trumpeting their transparency and independence, some think tanks offer their corporate members high levels of participation in their activities. This level usually raises with the membership fee. For example the Atlantic Council states its “corporate program engages the private sector as a crucial partner”. Friends of Europe's “President's Network” may “shape Friends of Europe's agenda (while respecting its independence) by suggesting topics of interest that [Friends of Europe] may cover”. And “joining Bruegel’s Membership Programme will allow you to… engage with recognized scholars, decision-makers from the private sector, and policymakers at every governance level.”

In some cases, think tank members can therefore co-decide what the think tank should be thinking about, and are provided access to exclusive events and high-level decision-makers. When looking at some think tanks' members lists, a high percentage of corporate institutions can be found. A question to be raised here is: how independent can you be whilst not biting the hand that feeds you?

Friends of Europe = Friends of Big Corporations?

Think tank Friends of Europe is known for its grandiose events (often sponsored by corporations), which provide interesting lobbying opportunities. For example, in July 2015 it organized an event entitled 'The New Geopolitics of Energy – Winners and Losers', in association with energy companies Engie and Statoil and two MEPs as speakers.30 This was followed in October by, 'Working towards a Sustainable Global Food system', co-organized with agribusiness giant Cargill, with speakers from the Commission's Directorate General on Agriculture and food giant Mondelez. In November Friends of Europe held 'World Energy Outlook – Europe's option in a volatile world' with partners including Statoil and chemicals company Solvay, speakers from Statoil and energy company E.ON, and Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič, the EU's Vice-President for the Energy Union. The think tank also co-writes reports with corporations, such as one with Google on 'Digital Skills. Creating Economic Growth Across Europe', and has just launched a Prize Essay Competition with management consulting firm McKinsey, offering prize money to those with the best ideas on how to push a pro-growth reform programme in Europe.31

Its members32 include powerful players from various industries: chemical (Dow, BASF), Big Oil (Shell, Chevron, ExxonMobil and many other usual suspects), food and agribusiness (Cargill), digital (IBM, Facebook, Siemens, Philips), pharmaceutical, car, financial, defence, etc.

To become a member, associations pay between €500 (NGOs) and €2,050 (corporations) per year. VIP members have to cough up between €1,750 (NGOs) and €6,850 (corporates). Among other privileges, members are offered “exclusive access to [its] latest policy analysis and conferences”, “maximum visibility during [its] events and input into [its] activities” and “unparalleled opportunities to expand and build contacts.” VIP members, then, receive even more exclusive invitations, such as dinner debates with representatives from EU institutions and other high-level gatherings.

Of course, “[it] goes without saying that Friends of Europe does not represent the interests of its members, most of whom in any case have competing or conflicting interests”, they claim; “Friends of Europe’s hallmark since its earliest days has been its independence: We have no national or party political bias, nor do we advance the interests of any of the organisations we partner with.”

True, in the market-place their members compete. But when it comes to policy, this picture changes. On policy level, corporations' interests are often very much aligned. Hence why they get together in business associations. Similar to these associations, Friends of Europe might say it does not lobby on behalf of a specific member, however it advocates certain positions most – if not all – of its members would agree with.

Not surprisingly, Friends of Europe counts some influential personalities among its ranks. Its president is Viscount Etienne Davignon who served twice as Commissioner, is Vice-Chair of Suez-Tractebel, is sometimes referred to as “the most powerful Belgian”,33 and was a member of the European Roundtable of Industrialists (ERT) – one of Europe’s most powerful lobby groups. Further, on its Board of Trustees we find: former European Parliament President Pat Cox, who after being an MEP for fifteen years and President of the EP for two years, became a lobbying consultant for various organisations, including Microsoft and Pfizer; former commissioners Joaquín Almunia, László Andor (the latter two are also on the boards of three other think tanks mentioned below), Michel Barnier, Štefan Füle, Andris Piebalgs, Androulla Vassiliou; former and current MEPs such as Elmar Brok and Hans-Gert Pöttering;34members of parliamentary groups from across the political spectrum; people with (previously) high profile roles on national level;35former Director General of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) Pascal Lamy, and last but not least, ERT member and chemical giant Solvay Director Baron Daniel Janssen.

Since March 2015 Friends of Europe has had at least ten meetings with high-level Commission officials on matters such as Energy Union, TTIP, green growth, and the “circular economy”.36Two of these were public events under the format of a one-hour “conversation with” the commissioner in question.37The think tank discloses less than €9,999 lobby expenses in Transparency Register, but yet 27.5 full time equivalent lobbyists. One employee has a European Parliament pass for 2015/2016.

When asking Friends of Europe about their unrealistically low lobby expenses, they replied that with the current definition of activities covered by the Register, “in a large interpretation virtually all of Friends of Europe's activities and budget may be said to fall under [it].” They further state the broad definition of the scope of the Register has created ambiguity, leading to different interpretations among think tanks. “Given the specificity of a think tank’s independent work, we have asked the European Commission to examine whether a distinction can be made in the register between direct lobbying budgets (zero for Friends of Europe) and activities that can indirectly influence EU policymaking such as the work of think tanks in which case we would probably put our entire budget, as we don’t know how we could distinguish costs for accounting, IT, etc from costs linked to organising debates or publishing reports.”38

Centre for European Policy Studies for carbon markets and TTIP

The Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) is the think tank with the greatest number of encounters with Commission officials since December 2014: at least 20. Two of these are events where the Commission official appeared as a speaker,39the others appear to be meetings. Founded in 1983, CEPS is one of the oldest and most influential think tanks in Brussels. A “forum for debate on EU affairs”, it organises events and carries out research on a variety of topics. The Centre has an impressive list of corporate and institutional members, including big financial players;40Big Energy41and tobacco (Japan Tobacco International).

The largest chunk of CEPS' income42comes from the Commission (45 per cent). Membership fees account for about 18 per cent of CEPS’ budget for 2016: “CEPS Corporate Membership fees vary according to the size and structure of the company concerned, from €6,000 to €18,000” while Inner Circle Corporate Membership has a price tag of €30,000.

Like Friends of Europe, CEPS often gives prominent platforms to its corporate members, organising events in cooperation (for example with Telefonica and Shell), or gives them credibility by speaking at their events, eg a REPSOL-organised event on “Energy for Europe”.43Last year CEPS co-organised a lunch meeting with the European Services Forum (ESF)44– one of the main lobby groups pushing for TTIP45– on “why services are critical in TTIP.” Marco Duerkop, TTIP negotiator for services, DG Trade, was a speaker. This comes down to what the Centre offers its corporate members, who “also enjoy the opportunity to interface directly with EU decision-makers in a variety of settings, both formal and informal, to contribute their views to the policy-making process”.

CEPS has gladly adopted conveniently connected members on its Board of Directors. Many are directly plucked from the Commission, the Parliament, national governments and influential companies. These include Joaquín Almunia, former Barroso II competition Commissioner and also a member of the Friends of Europe Board; Danuta Hübner, MEP; John Bruton, former Prime Minister of Ireland; Edmond Alphandéry, former Economic Minister of France; Edelgard Bulmahn, member of the German Bundestag and Onno Ruding, former Minister for Finance of the Netherlands, also retired vice chairman of Citibank and member of the Larosière group, a.k.a. Barroso’s group of wise men to advise on the financial crisis (see above). And, also in the list: veteran ERT member Etienne Davignon.

In the Register,46besides indicating less than €9,999 lobby costs, CEPS declares 50 full time equivalent lobbyists and 4 employees holding a European Parliament pass. When querying these seemingly low lobby costs – given the high number of full time equivalents and high-level Commission meetings – CEPS replied:

The meetings with Commission officials... have all happened within this framework: Either to carry out interviews to complement our theoretical research, or to discuss (in public debates) the main findings of our studies. We organise a range of meetings in which public officials, company representatives (across sectors, and countries), and other stakeholders meet and debate. Neither of these activities is designed to influence, directly or indirectly, policy-making by putting forward a specific interest - which is what lobbying implies.

A think tank has the role of putting on the table constructive, well-thought-through, and well-argumented new ideas. Since we are one of several think tanks active in Brussels, these proposals may or may not be taken into account by EU policy-makers. They are meant to stimulate effective policy making, and to "thinking ahead for Europe" as outlined in our motto.

As to the access to European institutions: We have a team working on external relations that supports researchers in getting their work promoted. They engage with members of the EP and the EC, also in preparation for our events, and thus we do have access passes (used to very different extents). This is why we indicate less than €9.999 as the costs related to activities of interest representation. If a box with the amount €0 was available, we would have ticked that box.

…. None of our fifty-something employees is paid for directly or indirectly lobbying the EU Institutions (or any other institution, for that matters). Thus, we incur no costs for lobbying activities, which we do not carry out.47

However, whether or not it is the goal of its activities, CEPS does provide a platform for corporations to put forward certain arguments – thereby giving them credibility on controversial subjects (eg to Shell or Repsol on climate). And it creates the space for corporate lobbyists to interact with policy-makers, in different settings. CEPS may not directly influence policy-making, but the think tank is an important player when it comes to creating channels for certain interests towards policy-makers. Here and there footprints can be found of these interests. For example, with the help of Andrei Marcu, head of the CEPS Carbon Market Forum, the think tank has become one of the architects behind the EU's push for carbon markets, which is a heavily-corporate driven agenda.

Direct interest representation? Maybe not. Indirect? Definitely.

European Policy Centre – stimulating 'public debate' through exclusive events

The think tank European Policy Centre (EPC) is based in Brussels near the European Parliament. It works on a variety of topics such as European integration, energy, the promotion of economic growth and the future of the European Monetary Union and the Eurozone.48Since December 2014, EPC has had at least nine meetings with Commission officials on a variety of subjects.

Like other think tanks, EPC claims not to lobby. In its Register entry it presents itself as an “independent, not-for-profit think tank” and states that “it does not represent any individual interest group and does not allocate funds for lobbying”. Yet, in the same entry for 2014 it declared 25 full time equivalent lobbyists and estimated lobby costs of €2,250,000-€2,499,999, which is higher than its disclosed total budget for that year.49For 2015 its total budget did fall within the declared range of lobby costs.50

Its very extended list of members includes various influential players from Big Oil51and the chemical industry,52as well as tobacco companies BAT and Philip Morris, and cigarettes manufacturers lobby group Confederation of European Community Cigarette Manufacturers (CECCM). Different membership fees apply to various categories, ranging between €2,500 and €10,000 annually for corporate members. Being a member gives free access to various EPC events, where “key figures in government, industry and the EU institutions take the floor”. While the EPC claims to stimulate “public debate”, these exclusive events “are only open to EPC members, EU officials and the media, unless specified otherwise”. So much for 'public' debate.

As became clear from the names on its list of members, EPC is very well connected to big industry. Further, from the looks of the members of the governing board, it is clear they are also much connected to the world of politics. It includes: Poul Skytte Christoffersen, former Permanent Representative of Denmark to the EU; Fabio Colasanti, former European Commission Director General for Information Society and Media; Yiva Tivéus, former Director of DG Communication, and Andrew Duff, former MEP. Its Advisory Council, besides being presided by Herman Van Rompuy, ex-President of the European Council, is packed with former Commission officials (including recent departees Connie Hedegaard, Joaquin Almunia, Lászlo Andor, Janez Potočnik, and others who have passed through the revolving doors) as well as former and current MEPs, such as Erika Mann, who after serving as an MEP, where she spoke in favour of EU-US trade liberalisation, entered straight into the lobby world through the Computer and Communications Industry Association, followed by Facebook.53Also national representatives from Germany, Sweden, and representatives from companies like General Electric (GE), British Telecommunications (BT), DHL and Johnson & Johnson take part.

Bruegel's research agenda influenced by members

Bruegel, a Brussels-based neoliberal think-tank working on international economic policy gives an overview of its members in its annual report and through its website. In 2015, it received a high score on Transparify's report54on Think Tanks Transparency to which Bruegel's Secretary General Matt Dann reacted: “Since Transparify’s assessment last year, there has been a significant overall improvement in the global think tank sector towards sharing funding sources with the public. We welcome this development, as the level of transparency in our sector affects the reputation of us all. … If funder or think tank is unwilling to share this information, both should reflect on why – the public certainly will!”

CEO also believes that making this information available to the public is of vital importance, to allow for proper scrutiny. However, transparency should not be confused with independence. Through its Transparency Register entry, Bruegel claims not to “have a budget for direct representation of “interests” as it is not an interest representing organisation – it is a public good... with checks and balances in place to safeguard its independence, even from its members and other stakeholders.” In its statute it states “Members shall not try to influence the results of research carried out at the Association or obstruct its dissemination.”

On the other hand, over half of its corporate members55come from the financial sector, and benefits for members include contributing to “setting Bruegel's research agenda” and engaging with “scholars, decision-makers from the private sector, and policymakers at every governance level (global, EU and national)”. Most corporate members (eg BBVA, Goldman Sachs, Google, EDF, Shell, etc) have paid a subscription fee of €50,000 in 2014.

Moreover, Bruegel is at the top of the list of think tanks that have had meetings with the Commission on high levels: at least 16 meetings have taken place since December 2014, chiefly on financial industry related topics.

A couple of months after his departure from the European Central Bank (ECB), Jean-Claude Trichet became Bruegel's chairman. Trichet currently chairs the banking lobby 'Group of Thirty', whose members are central bankers and bankers from large private banks. Set up to discuss global banking regulation, it often agrees with pro-private bank proposals. Bruegel’s Director, Guntram Wolff, equally “joined Bruegel from the European Commission”, prior to which he worked for the Deutsche Bundesbank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

For 2014, Bruegel estimated its lobby costs to be below €9,999, while at the same time declaring 18.75 full time equivalent lobbyists. After CEO had flagged up that activities covered by the Register cover “all activities designed to influence - directly or indirectly - policymaking, policy implementation and decision-making in the EU institutions",56Bruegel has adapted its entry. It now declares between €3,750,000 and €3,999,999 lobby costs.57

Atlantic Council – Boosting business across the Atlantic

The Atlantic Council – set up in the 1960s to boost political support for NATO, today still active on transatlantic security issues and the promotion of “further transatlantic economic integration and cooperation” – has about 100 companies among its corporate membership. On the website, it reads: “[t]he Atlantic Council's corporate program engages the private sector as a crucial partner. Through substantive partnerships, networking opportunities, event sponsorship, and corporate membership, the program provides partners unique opportunities to achieve business and corporate responsibility goals”. Depending on the yearly fee a company contributes, it falls under the “President's Circle” ($25,000-$49,999), the “Chairman's Circle” ($50,000-$99,999) or the “Global Leadership Circle” ($100,000 and above).

The President's Circle lists oil companies BP, ExxonMobil, Shell, and Statoil; multinational aerospace and defence company Boeing, American public relations giant Edelman; the US Chamber of Commerce, and others. The Chairman's Circle includes companies like Italian oil and gas company Eni, pharmaceutical companies Novartis and Pfizer, and The Coca-Cola Company. The 14 companies in the image above represent the Council's Global Leadership Circle. It is stated that senior leaders of these corporations serve as individual members of a network, providing companies with “timely information and access to thought leaders”.

About eight high-level Commission meetings with the Atlantic Council are registered, at least four of them discussing digital issues. For 2014, the Council declared between €300,000 and €399,999 lobbying expenses and 2.2 full time equivalent lobbyists.

Towards more realistic Register entries

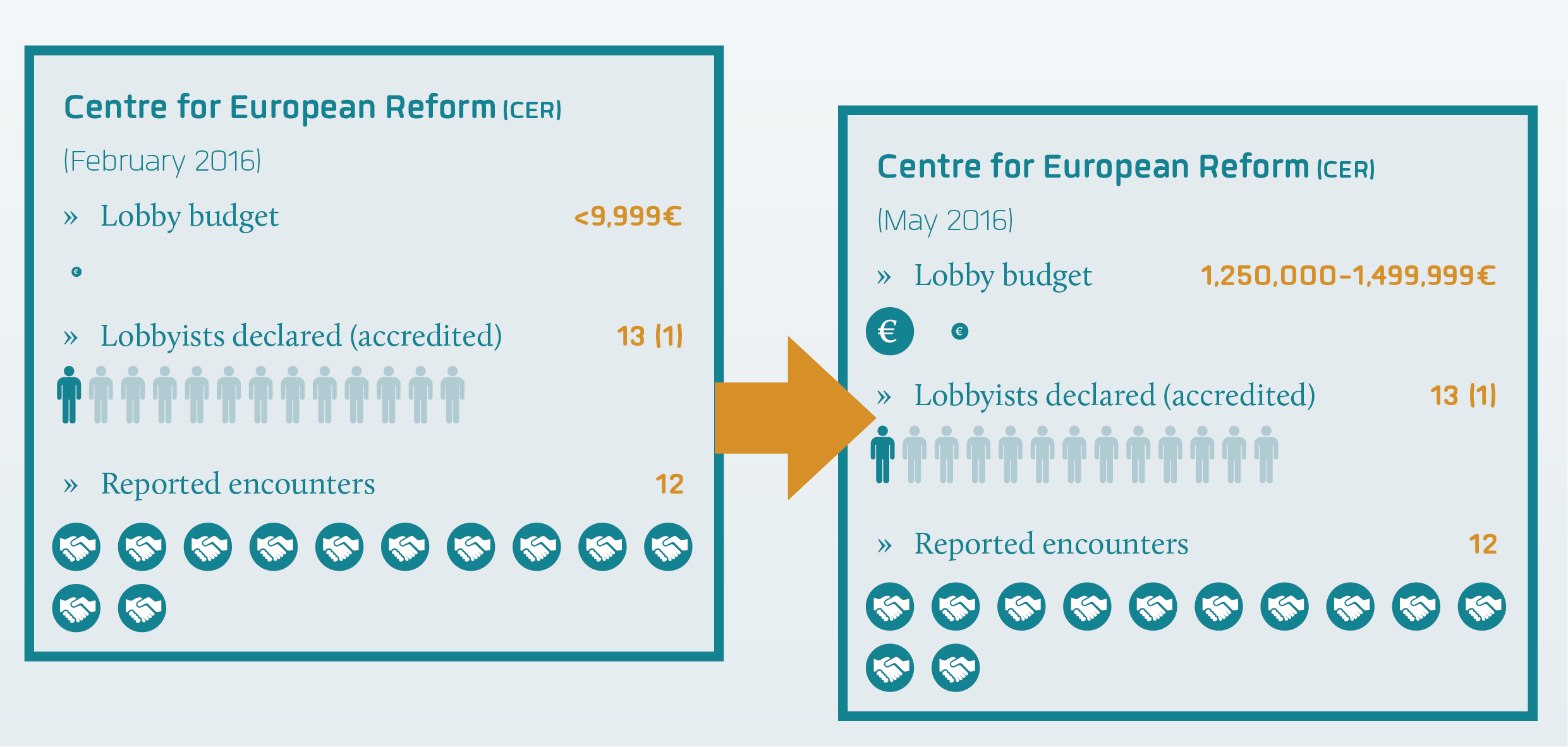

The London-based Centre for European Reform (CER) – “pro-European but not uncritical” – looks into global political and economical relationships, “devoted to making the European Union work better and strengthening its role in the world”. It organises events – bringing together “opinion-formers”, “by invitation only and off the record, to ensure a high level of debate” – and carries out research for its publications or for private policy papers.

CER lists its donors in its “Transparency document 2014-15.” It seems its transparency has improved since February last year, when they received a low rating in the Transparify report. Corporate Donors 2014-15 include some big financial, digital and energy players,58 who each pay between €11,000 and €50,000 per year. CER also hosts many events alongside Kreab, a major Brussels lobby consultancy, and representatives of GDF Suez and BG (British Gas) are on its Advisory Board.

Joaquín Almunia – besides sitting on Friends of Europe, CEPS, and EPC Boards – also sits on the Advisory Board of CER, together with Philip Lowe, former Director-General of the European Commission's DG Energy; Carl Bildt, former Prime Minister and Foreign Minister of Sweden, and Mario Monti, former Italian Prime Minister.

CER used to declare low lobby spending in its Transparency Register entry (<€9,999), but since its update in March this year it declares €1,250,000 - €1,499,999. Like Bruegel, it is at the top of the list of think tanks with most registered high-level Commission encounters, having had at least 12 since December 2014. Both CER and Bruegel have updated their Register entry with higher – and thus more realistic – lobbying expenses this year.

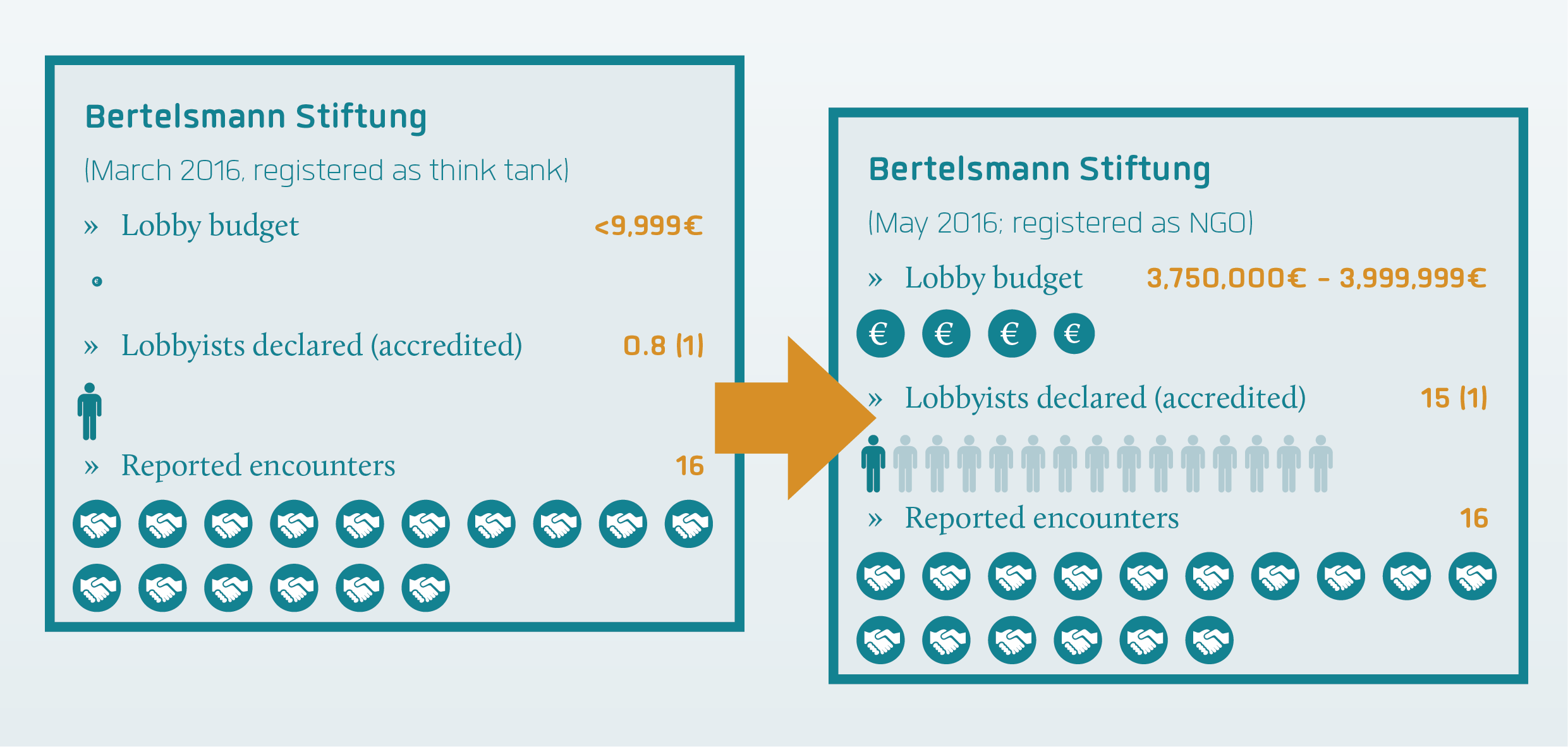

Also the Bertelsmann Stiftung or Bertelsmann Foundation – according to German watchdog Lobby Control “one of the most influential neoliberal think tanks in [Germany]”59– has upped its lobby costs. And has re-categorized itself. From previously declaring less than €9,999, registered as a think tank, it now declares over €3.5 million lobby expenses, and has instead listed itself as an NGO.

The Bertelsmann Stiftung is the main shareholder of Bertelsmann SE, one of Europe's largest media corporations,60who “controls RTL, the biggest private radio and TV broadcaster in Europe”.61The Foundation declares its goal is to “promote awareness of the Bertelsmann Stiftung as a source of new ideas. The Brussels team achieves this by cooperating closely with the major EU institutions and with experts”. Topics tackled in Brussels include “overcoming the euro crisis” and “achieving a competitive, socially just market economy.”62

One of the Foundation’s favourite topics is TTIP. In 2014, their proposal of a TTIP road show “that will showcase in selected US cities the potential benefits of a free-trade agreement between the EU and the US”, was selected by the Delegation of the EU to the US for a grant.63The Foundation organised a “TTIP Town Hall” tour64with stops in five US states, “dedicated to fostering greater American awareness of and debate on TTIP”. Wait. EU funds to promote the EU-US free trade agreement that in important sectors such as agriculture might well benefit the US more than the EU? Research has found, for example, that European small-scale farmers will mostly loose from this agreement.65This question should raise some eyebrows.

In 2013, the Foundation had the company of Benita Ferrero-Waldner, former Trade Commissioner, on its Board of Trustees, and previous Commissioner for Justice and current MEP Viviane Reding serves on Bertelsmann’s Board of Trustees today. Links with companies like Nestlé, Axa and McKinsey can equally be spotted. The Bertelsmann Foundation is a member of Friends of Europe and a supporter of the Atlantic Council.66

The Register's definition of NGO includes independence from commercial organisations.67Is this the case for the Bertelsmann Foundation?

Among think tanks, the Foundation is near the top of the list in securing meetings with high-level Commission staff, with 16 registered encounters since March 2015. When it comes to declared lobby expenditure, it currently finds itself among the biggest-spending German lobbyists in Brussels, together with Deutsche Bank and VW. Its office in Brussels is situated in the Residence Palace, with a view onto the Berlaymont building.

Open Europe: Open about goals, opaque about funding

For other think tanks, links to the corporate world are visible, while funding sources remain rather opaque.

Open Europe, for example, a London and Brussels-based free market think tank, was set up in 2005 by “some of the UK's leading business people”. It produces research on a variety of topics relating to EU policy and declares its goal is to radically reform the EU, which would encompass its aim “to counter taxpayer-funded groups who favour more EU intervention”.

Open Europe's research and viewpoints often feature in the UK media. Recently its stance in the UK referendum on whether to leave the EU was sought by many. As stated on its website, Open Europe decided to remain neutral in that debate. Chairman Lord Leach of Fairford said: “We nonetheless share a common belief that Britain can continue to be successful either inside or outside of the EU if it pursues free market and liberal economic policies.”68

Open Europe's former Director, Mats Persson, passed through the revolving door when he became special adviser to UK Prime Minister David Cameron after leaving Open Europe in May 2015.

One of the topics on which Open Europe has carried out some serious lobbying is the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD), proposed by the Commission in 2009. The goal of this directive is the regulation of hedge funds and private equity funds.69Following heavy lobbying by the financial industry the hedge funds and private equity fund lobby groups managed to “win what has been the first really open political battle on financial regulation in the history of the European Union”.70Open Europe played its role then, and also recently put forward proposals in this area, in a report published jointly with the New City Initiative, a 'think tank' comprising “52 leading independent asset management firms from the UK and the Continent.”71

On the website’s donate page, it reads: “Unlike most other leading think-tanks and organisations dealing with EU policy, we do not accept money from the EU institutions, governments or big corporations.” However, their list of supporters – who support Open Europe “in a personal capacity” – includes an Easy Jet chairman, a Reuters Director, Unilever's Former Finance Director, JP Morgan's Vice Chairman, HSBC Holdings' Deputy Chairman, and Next's CEO. Further, no precise information on funding sources is provided, neither on Open Europe's website, nor in the lobby Register.

The lack of information on who funds whom prevents external scrutiny. CEO calls for an urgent reform of the Register, obliging lobby actors to provide this kind of data.

Open Europe declares between €25,000 and €49,999 lobby costs and eight time full equivalent lobbyists. It has had at least six high-level Commission encounters since December 2014.

Lisbon Council thinking Digital

The Lisbon Council – a think tank and policy network promoting free market reforms, based in the heart of the EU quarter in Brussels – is also rather opaque about its funding. In its 2014 annual report one can see that in 2014, 100 per cent of its funding came from donations. In 2013 about 20 per cent also came from grants. Donations come from “leading corporations and foundations”. Gratitude goes out to companies like Accenture – with whom the Council has co-written a number of publications72– as well as Apple, Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria (BBVA), IBM, Philips, and Telefónica. What (or how much) exactly they are grateful for, however, is unclear from the report.

The Council's website and its entry in the Transparency Register assure that it “is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan association” and that “[s]upport for the Lisbon Council’s activities does not constitute endorsement of any statement, view or initiative of the Lisbon Council or any of its associates.”73However, most of its acknowledged financial supporters have clear stakes in the digital and technology market. Furthermore, its advisory board includes representatives from Accenture, Philips, and IBM.

The Council's priorities seem to be close to the Commission’s Digital Economy programme.74Interestingly, in 2014 the Lisbon Council’s former executive director Ann Mettler was recruited by the Commission as Head of the European Political Strategy Centre (EPSC), Juncker’s “in-house think tank”. In a press release by the Commission it reads: “Ms Mettler's... experience will also help boost relations between the European Commission and decision-makers, think tanks and civil society at large.” CEO has expressed its concerns about the handling of Mettler's appointment by the Commission, who states that its “rules on conflict of interest... were applied in this case”.

As head of the EPSC, out of the 44 meetings Mettler has had with lobbyists, at least 17 were indeed with think tanks.75Including: CER, Bertelsmann Stiftung (twice), Friends of Europe, Atlantic Council, Bruegel, EPC, and CEPS.

Like Open Europe, the Lisbon Council is not exactly transparent about its funding sources. No specific funding amounts can be found in its Register entry, nor on its website.

The Council has had at least five high-level meetings with the Commission, of which two were on start-ups and two on the digital single market. For 2014, the Council discloses six full time equivalent lobbyists and not more than €9,999 lobby costs. We received no answer to our query on this seemingly low lobbying expenditure.

Jacques Delors and Jonathan Faull

Institut Jacques Delors (previously Notre Europe) – the think tank set up by Jacques Delors after his presidency at the Commission – publishes the details of its financial resources in its annual report (2014 version). The majority of the contributions seem to come from the European Commission, Fonds Notre Europe, and the French Government. Among the other supporting partners, published on the website, we can find electric utility company GDF Suez (now Engie) and Caisse des Dépôts, a French state-owned investment group.76

A list of donors is published and for 2015 it includes people like Fredrik Erixon, founder of the ECIPE think tank (see below); Jonathan Faull, a long time Commission official who recently led the UK referendum (Brexit) taskforce; Pieter Van Nuffel, Commission President Juncker's Personal Representative in the Cyprus settlement negotiations; and various people working at the Institute, such as Director Yves Bertoncini, also head of international affairs at FFSA, a French lobby group working active in the field of finance and insurance. However, these donor contributions seem not to be included in the annual report's financial overview.

The Institute's Transparency Register's entry is confusing, with lobby costs declared (€1,435,661) greater than total budget declared (€1,410,130), without any explanation provided on why this is the case. It declares 7.5 full time equivalent lobbyists and one meeting with the Commission is registered with Jonathan Faull, also on the list of donors.

Thinking and dreaming about free trade

The European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE) is a Stockholm- and Brussels-based think tank “rooted in the classical tradition of free trade and an open world economic order”. It was founded by Fredrik Erixon, who has worked as economist in the Swedish Prime Minister’s office, as adviser to the British Government, for JP Morgan, at the World Bank, and at Timbro, an influential Swedish liberal think tank. ECIPE's co-founder and Director, Razeen Sally, is adjunct scholar at the American libertarian think tank Cato Institute, and was awarded the Hayek Medal in 2011. He is involved with the World Economic Forum and the neoliberal Mont Pelerin Society. Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, also director, was the team leader of the Trade Sustainability Impact Assessment of the EU-Japan Free Trade Agreement, in his role of visiting fellow at the London School of Economics (LSE).77

Among ECIPE's Advisory Board we can find more 'free trade' links through people previously active at WTO and General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT); as well as links with American think tanks such as the Cato Institute and the Brookings Institution.

For the year 2014, ECIPE declares €900,000 budget in the Transparency Register. The main part of its funding comes from the Swedish Free Enterprise Foundation,78the major employers' organisation for private sector and business sector companies in Sweden. It also “welcomes financial support from individuals, foundations and other organisations sharing [its] ideas in favour of an open world economic order based on voluntary exchange and free trade.” Specific details on funding sources are absent.

ECIPE has had at least four meetings with high-level Commission officials. Nevertheless, in its Transparency Register entry, where it indicates seven full time equivalent lobbyists, it reads “we do not engage in lobbying” and that its lobby expenditure is below <€9,999.79CEO asked why ECIPE declares such low lobby expenditure. We received no reply.

Welcome, EPICENTER, to the Register

One interesting group that recently signed up for the Transparency Register is the European Policy Information Center (EPICENTER), an “independent initiative of six leading think tanks from across the European Union. It seeks to inform the EU policy debate”. It was launched in 2014 by Civismo (Spain), the Institut Economique Molinari (France), the Institute of Economic Affairs (UK), the Lithuanian Free Market Institute, Timbro (Sweden) and Istituto Bruno Leoni (Italy). Out of these six, only Istituto Bruno Leoni and the Lithuanian Free Market Institute can be found in the EU's Transparency Register.

All of them are within the Global Directory of the Atlas Network, connecting free-market organisations worldwide, pushing for limited government regulation, private property protection, and free markets. The English Institute of Economics Affairs – following the Atlas Network, “laying the intellectual foundations for [Margaret Thatcher's] market-oriented reforms” – was established by Anthony Fisher, who thereafter founded the Atlas Network with the objective of replicating Thatcher's model of “popularizing free-market ideas via independent think tanks”. The IEA is also the initiator of the Nanny State Index, “a league table of the worst places in the European Union to eat, drink, smoke and vape”, basically indicating in which countries unhealthy products are cheaper and less regulated.

The Institut Economique Molinari is a francophone think tank that in the past has taken climate change denying stances, publishes articles defending genetic modification and speaking against the precautionary principle. It is founded by Cécile Philippe, who once stated that “austerity is at the service of sustainable development”.

How EPICENTER is funded is not very clear from its website, nor from its entry in the Register. We are only told that “[l]ike its members, EPICENTER is politically independent and does not accept taxpayer funding”. Receiving funds from big tobacco giants like Philip Morris, on the other hand, does not seem to be a problem for one of its founding members, the Lithuanian Free Market Institute. EPICENTER's Director is Gustav Blix, former Swedish MP (2006-2014) with “an extensive background in politics and the promotion of free-market ideas and principles.” Where it is currently located is unclear from the website, but rumour has it it will soon be settling in Brussels,80where most of its events take place.81

EPICENTER declares three full time equivalent lobbyists, but no lobby costs as yet. The Register provides the opportunity for newly-registered organisations to not declare lobby costs for one year, if such costs were not incurred. EPICENTER was launched in 2014 but has not yet declared any lobby costs.

Transparency Register inconsistencies

Since 2011, many of the think tanks previously refusing to register have added their organisation and data to the lobby Register. However, being in the Transparency Register does not necessarily mean they are fully transparent. For example, as we have already seen, there is sometimes a disparity between asserted lobby costs, full time equivalent lobbyists, and the number of registered high-level Commission encounters.

Other think tanks clearly influencing European policymaking are still missing from the Register, such as the Centre for Economic Policy Research and the Thomas More Institute. Technically, commissioners and high-level Commission officials are not allowed to meet with unregistered lobbies,82so they have to find other creative ways to make their voices heard.

High level Commission meetings, low level declared lobby spending

Of the 19 organisations we looked at, 17 are (or were) in the Transparency Register under the category of 'think tank'. At least half of them have an office in Brussels. In March 2016, out of the 16 then registered under the think tank category, nine claimed their lobby costs to be below €9,999. Out of these nine, with the exception of EFILA, all of them have had at least five (registered) encounters with high-level members of the Commission since December 2014. Out of all 19, more than half declared more than five full time equivalent lobbyists working on their behalf. But unless they work for free or someone else pays them, a total lobby spend of less than €9,999 seems like a suspiciously low cost for the lobby activity they indicate.

I (say I) don't lobby therefore I should not register

Even though the Transparency Register was brought to life almost a decade ago, and time has moved on since many think tanks refused to register in 2009, there are still a number of European policy-influencing think tanks out there that remain absent from the Register.

One interesting example is the London-based Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), founded to “enhance the quality of economic policy-making within Europe and beyond.” Its members include a considerable list of central banks – eg Banca d'Italia, Banco de España, Bank of Israel, Deutsche Bundesbank, ECB – and corporates from the financial industry, such as Citigroup, Credit Suisse, Grupo Santander ,and JP Morgan. CEPR's events are often co-organized or sponsored by a financial institution,83and it regularly hosts events in Brussels.

Depending on the member's contribution (or in CEPR language: “commitment”), different benefits apply. 'Gold' members contribute €10,000 annually, 'Platinum' ones €20,000. The former receive an invitation to the Centre's annual Roundtable, reuniting CEPR members, funders and policy-makers. They can also choose to sponsor events of their interest and have CEPR researcher at their disposal to attend their meetings and seminars. The latter ones also receive an invitation to the President's Circle, a “forum for frank exchange of views between leaders of the financial and central banking community, key decision makers and top academics”. The Circle and its members make suggestions on CEPR's research and policy direction. Can you hear the research independence alarm bells ring?

One example of a CEPR research was a report which formed the basis of a 2013 Commission Impact Assessment on the EU-US trade deal TTIP. The study alleges an average European household would gain an extra €545 per year if the deal were to go through. This report, quoted by the Commission, has since been criticised by Clive George, Professor at the College of Europe in Bruges, who has carried out impact assessments for the Commission in the past.84

CEPR boasts that its conferences are of an “unrivalled standard”. “After more than 30 years of bringing economists together, CEPR is well known in the public and private sectors and is able to attract high calibre audiences of key decision-makers and opinion-brokers across business and government.” Adding a layer to CEPR's exclusivity, “[p]articipation in workshops and conferences is limited and by invitation only”.

When asking why CEPR is not in the Transparency Register, CEO received no reply.

Another European policy-influencing think tank is the Thomas More Institute. With offices in Paris and Brussels, the Institute's “primary goal is to influence European decision-making bodies, at both community and national levels.” Its Board of Trustees is well connected to the political sphere, both in France as on European level. For example, one of its members, Stéphane Buffetaut, is today Chair of a section of the European Economic and Social Committee. Others include (former) French mayors or officials on national level. The Advisory Board includes Paul Goldschmidt, former Director at Goldman Sachs International in London and former Head of the Financial Transactions section within DG ECFIN.85 For funding the Institute seems to depend on memberships and donations; no clear link to names of supporters is provided.

CEO received no reply to its query on why the Thomas More Institute is not in the Transparency Register.

Summing up

As becomes clear from this list of examples, besides 'thinking', some think tanks also do lobbying – or they certainly provide a convenient channel to assist corporations with their own lobbying. Being a think tank, or pretending to be one, has become a lobby strategy in the Brussels bubble with many benefits attached. On the one hand, it gives the idea of objectivity and openness for debate, functioning as a cover for the interests behind. And on the other hand, it gives members and followers the opportunity to network on many levels, including informal encounters between lobbyists and Commission officials.

Think tanks have become influential Brussels bubble players, intertwining closely with corporate interests. Whether it is organisations labelled as think tanks set up to promote a particular corporate sector, or actual institutes that carry out research on certain topics, being open about funding is key. A number of think tanks seem to have accepted this and become more transparent, but others have more to do.

Further, when looking at the data, it appears that the lobby Register is not taken seriously by many of those listed in it. Nor are there any serious consequences given for incorrect reporting. In the case of think tanks, it is not clear who or what should fall under this category. Or what should be reported. Further, for those who don't need meetings with high-level Commission officials, the Register is still not obligatory. These and other loopholes mean that there are still big transparency gaps, meaning that the public and other stakeholders remain uninformed on who really influences decision-making processes.

Together with ALTER-EU (the Alliance for Lobbying Transparency and Ethics Regulation), Corporate Europe Observatory calls for a legally-binding lobby register, requiring disclosure of precise funding sources. This should apply to think tanks as well, going beyond merely labelling funding sources as either public or private, and with a Register secretariat with the powers to get tough with those who don't sign up or who post incorrect or misleading info. This is necessary to enable for external evaluation of corporate influence of policy debates via think tanks.

Further, corporations themselves must disclose all third-party funding that they provide, including for think tanks. This way it will be possible to gain a more complete and thus realistic picture of an organisation's full lobby footprint.86 Citizens of the EU and beyond have the right to know who is lobbying who and on what.

Beyond transparency, it is long overdue for the European decision-makers to take a long hard look at the think tanks aiming to influence their thinking – and their corporate backers.

Appendix I: Methodology

The data on the number of encounters is taken from the IntegrityWatch website: www.integritywatch.eu. As in some cases meetings/events are registered by different attendees, eg events where various Commission officials are present, it is possible these show up various times on IntegrityWatch. Throughout this article, the number that IntegrityWatch indicates is referred to as 'encounters'. The number of 'meetings' is estimated by looking at this list of encounters, and deducting the number of encounters with the same date and same topic that show up more than once, assuming it is the same meeting/event. Throughout the article, in most cases, no difference is made between a meeting and an event where the Commissioner in question was present. To have information on the type of encounter, one should look into the details of each item in the list.

- 1. Steve Waters, Dangerous Minds, 10 November 2004, The Guardian , http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2004/nov/10/thinktanks.uk

- 2. Jordi Blanes i Vidal, Mirko Draca, Christian Fons-Rosen, 'Revolving Door Lobbyists', Stanford University 2010. https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/documents/pe_03_11_vidal.pdf">https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/documents/pe_03_11_vida.... This research from the US shows the value added of a lobbyist when he/she has personal connections with elected representatives.

- 3. Op cit, Steve Waters, The Guardian.

- 4. The European Transparency Initiative was launched in 2005, the Commission's online register of interest representatives in 2008, and the Commission and European Parliament Joint Transparency Register in 2011 (http://ec.europa.eu/transparencyregister/public/staticPage/displayStatic...). Results from a 2006 CEO survey (http://archive.corporateeurope.org/docs/ThinkTankSurvey2006.pdf) found that a wide range of think tanks had not registered yet, nor was information on funding to be found on their websites (https://web.archive.org/web/20061218184119/http:/www.corporateeurope.org...). In 2010 another CEO report concluded that climate change denying think tanks funding remained severely opaque (http://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/sites/default/files/files...). For years, think tanks would refuse to register as they did not see themselves as 'lobbyists'.

- 5. Www.integritywatch.eu: a tool which, amongst other things, collects data on lobbying in Brussels. “For that we have combined the records of lobby meetings at the European Commission with the information contained in the EU Transparency Register – the register of Brussels lobbyists.” (http://www.integritywatch.eu/about.html)

- 6. CEPS (24), E3G (23), Bruegel (17), Bertelsmann Stiftung (16), Conseil de Coopération Economique (15), CER (12), Friends of Europe (11), EPC (10).

- 7. True on April 24th 2016.

- 8. On the difference between 'encounters' and 'meetings' with Commission officials, used throughout this text, see Appendix I on methodology.

- 9. True on April 24th 2016

- 10. This was true on 13/04/2016

- 11. https://www.weforum.org/people/andrea-canino

- 12. http://ec.europa.eu/commission/agenda/all_en?date_filter[min]=2016-03-07&date_filter[max]=2021-03-07&field_editorial_section_multiple_tid=All&page=62

- 13. http://ec.europa.eu/avservices/photo/photoDetails.cfm?sitelang=fr&ref=022844#0

- 14. Including: Eurobank Ergasias, J&P-Avax, Eni, Biomérieux, Safran, Secil, Mytilineos Holdings, Electricité Réseau Distribution France (ERDF), Suez Environment, Acciona, Portucel Soporcel, Prisa & Eutelsat Communications

- 15. This was true on 10/04/2016

- 16. This was true on 13/04/2016

- 17. This was true on 24/04/2016

- 18. Read more on CCS in this CEO report: http://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/the_corporate_cookbook.pdf

- 19. http://hub.globalccsinstitute.com/sites/default/files/publications/197268/global-ccs-institute-annual-review-2015.pdf

- 20. McGlade and Ekins, (2015) ‘The geographical distribution of fossil fuels unused when limiting global warming to 2ºC’, Nature, 517: 187-190, www.nature.com/nature/journal/v517/n7533/full/nature14016.html

- 21. €11,936,400 of €12,210,800

- 22. http://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php/Global_Carbon_Capture_and_Storage_Institute

- 23. Compared to conventional oil extraction, tar sands produce three to four times more greenhouse gas emissions. Further, the extractive activities in the region have had and are having a huge impact on the local indigenous communities, as they see their lands degrade through the effects of mass deforestations, oil leaks, etc.

- 24. As a result the Keystone XL company TransCanada is now suing the US government for $15 billion under NAFTA (https://www.nrdc.org/stories/dirty-fight-over-canadian-tar-sands-oil). This case shows the danger of ISDS in trade treaties (https://euobserver.com/opinion/131756). 'ISDS' or Investor-State Dispute Settlement is a mechanism companies can use to circumvent domestic laws. It allows them to sue governments who make policy decisions that might decrease their profit-making hopes and expectations. If the company wins this settlement, it is taxpayers of the home state who end up paying. Recently (autumn 2015) the Commission proposed to replace the ISDS with ICS, which is short for 'Investment Court System' and essentially comes down to... the same thing (http://corporateeurope.org/international-trade/2016/02/zombie-isds ).

- 25. See footnote 24.

- 26. Achmea, Linklaters, Mannheimer Swartling, Herbert Smith Freehills, Luther Rechtsanwaltsgesellschaft mbH, NautaDutilh, Allen & Overy LLP, GREGORIOU & Associates LAW OFFICES, Kubas Kos Gałkowski and White & Case

- 27. EFILA membership list [http://efila.org/current-members/] and EU Transparency Register, as of 06/04/2016.

- 28. Information via CEO's lobby facts research [14.06.2016], as yet unpublished.

- 29. http://ec.europa.eu/transparencyregister/public/staticPage/displayStaticPage.do?locale=en&reference=WHOS_IS_EXPECTED_TO_REGISTER

- 30. Commission President Juncker was also repeatedly invited (http://www.asktheeu.org/en/request/2568/response/9419/attach/13/annex%20...), but Juncker's senior political adviser Telmo Baltazar gave a negative recommendation (http://www.asktheeu.org/en/request/2568/response/9419/attach/10/annex%20...), after which he send a reply denying the request on Juncker's behalf “due to existing commitments on the day in question.” (http://www.asktheeu.org/en/request/2568/response/9419/attach/11/annex%209.pdf)

- 31. With a “prize pool of €100,000 to the best essays that answer the question: How could a pro-growth reform programme be made deliverable by 2020, and appeal to electorates and decision makers alike at the national and European level?”

- 32. http://www.friendsofeurope.org/media/uploads/2014/10/Annex-I-List-of-2014-FOE-revenues-from-membership.pdf

- 33. eg http://nl.vivat.be/geld-bank/wie-is-de-machtigste-belg-van-de-wereld_1129

- 34. Also: Franziska Katharina Bratner, Monica Frassoni, Ana Gomes, Sylvie Goulard, Jacek Saryusz-Wolski and Marietje Schaake.

- 35. Carl Bildt in Sweden, Franziska Katharina Bratner in Germany, Elisabeth Guigou in France, Mario Monti in Italy, Jacek Saryusz-Wolski in Poland, Javier Solana and Anna Terrón in Spain, Herman Van Rompuy and Guy Verhofstadt in Belgium.

- 36. A proposed alternative model to the current economic system, where resources are retained in the product chain, instead of being thrown out. Following Karmenu Vella, EU Commissioner for the Environment “a new model, where we use resources more efficiently to boost Europe’s competitiveness”: http://ec.europa.eu/commission/2014-2019/vella/blog/circular-economy-investment-triple-win_en.

- 37. For example with Cecilia Malström on TTIP: http://www.friendsofeurope.org/event/trade-21st-century-challenge-regulatory-convergence/

- 38. E-mail correspondence between Friends of Europe and CEO

- 39. This number was become after comparing dates of CEPS’ past events (https://www.ceps.eu/past-events) with the dates of the registered meetings.

- 40. Such as: Allianz, BBVA, Banco Santander, Barclays, BNP Paribas, Crédit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, EIB, ING, JPMorgan, Nasdaq, Nordea Bank, Rabobank, Raiffeisen, Standard & Poor’s, Visa and Zürich Insurance Company

- 41. Including: EDF, ENEL, Eni, ExxonMobil, OMV Aktiengesellschaft, REPSOL, Shell, Statoil, Total, Vattenfall

- 42. “The breakdown of the 2016 budget does not include revenues earmarked for CEPS’ partners in externally-funded projects.”

- 43. Where participants would be “welcomed by Mr Antonio Brufau, Chairman of Repsol and Mr Miguel Arias Cañete, EU Commissioner for Climate Action and Energy”. Commissioner for Trade Cecilia Malström was also warmly invited (http://ec.europa.eu/carol/?fuseaction=download&documentId=090166e5a1180c...).

- 44. http://corporateeurope.org/trade/2013/02/your-service-european-services-forum-privileged-access-eu-commission

- 45. http://corporateeurope.org/international-trade/2015/07/ttip-corporate-lobbying-paradise

- 46. http://lobbyfacts.eu/representative/14e841815d9a4293b247f22ec9ac5754

- 47. E-mail correspondence between CEPS and CEO

- 48. http://www.epc.eu/press_room_details.php?release_id=37

- 49. This was true on 07/04/2016.

- 50. http://lobbyfacts.eu/representative/af2c3460b4334753b09e09445dff2a1e

- 51. Statoil, Chevron, EDF, ExxonMobil, OMV Aktiengesellschaft, Suez.

- 52. BASF, DuPont, Dow, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Cefic, EuropaBio.

- 53. Which she reportedly has now left to join lobbying-law firm Covington & Burling.

- 54. Transparify (http://www.transparify.org/about/) is a project providing a “global rating of the financial transparency of major think tanks”, funded by the Open Society Foundations (https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/about).

- 55. Published on its website membership page (http://bruegel.org/about/membership/) on April 19th 2016.

- 56. http://ec.europa.eu/transparencyregister/public/staticPage/displayStaticPage.do?locale=en&reference=WHOS_IS_EXPECTED_TO_REGISTER

- 57. E-mail correspondence between Bruegel and CEO

- 58. American Express, Deutsche Bank, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, Lloyds, Google, IBM, BP, EDF, Shell, Statoil

- 59. https://lobbypedia.de/wiki/Bertelsmann_Stiftung

- 60. https://lobbypedia.de/wiki/Bertelsmann_SE

- 61. https://www.rt.com/op-edge/333705-pro-eu-nato-lobbyists/

- 62. http://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/BSt/Publikationen/Infomaterialien/IN_Annual_Report_2014_06_2015.pdf

- 63. http://www.bfna.org/article/bertelsmann-foundation-receives-eu-grant-for-ttip-roadshow

- 64. http://www.bfna.org/page/ttip-town-hall-program/overview

- 65. http://www.euractiv.com/section/agriculture-food/news/ttip-the-downfall-of-eu-agriculture/

- 66. https://lobbypedia.de/wiki/Bertelsmann_Stiftung

- 67. See 2015 Guidelines.

- 68. http://openeurope.org.uk/today/vision/

- 69. Types of short term investments not open to the general public, but rather to 'institutional investors', such as banks, insurance companies, pension funds and very wealthy individuals. As for a long time they have gone unregulated, these types of funds – rather hidden but important players in the global financial system – come with various issues attached. See p. 2 and 3 of this CEO report on the regulation of investment funds: http://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/sites/default/files/files/article/regulating_investment_funds.pdf

- 70. http://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/sites/default/files/files/article/regulating_investment_funds.pdf

- 71. For more info on the power of the UK's financial sector in Brussels: http://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/ukfinancialfirepower.pdf

- 72. See POWERING INNOVATION TO DELIVER PUBLIC SERVICE FOR THE FUTURE (http://www.lisboncouncil.net/publication/publication/105-powering-innova...) and “Delivering public service for the future” (http://www.lisboncouncil.net/publication/publication/117-delivering-public-service-for-the-future.html ) (both also in collaboration with College of Europe).

- 73. This was true on 19 April 2016.

- 74. http://corporateeurope.org/revolvingdoorwatch/cases/ann-mettler

- 75. According to Integrity Watch (http://integritywatch.eu/) (last update: 12 April 2016).

- 76. http://www.bloomberg.com/research/stocks/private/snapshot.asp?privcapId=553777

- 77. http://www.tsia-eujapantrade.com/organisational-structure-of-the-tsia.html

- 78. http://ecipe.org/about-us/

- 79. This was true on 18 April 2016.

- 80. POLITICO Brussels Influence newsletter 29/03/2016

- 81. http://www.epicenternetwork.eu/events/

- 82. http://corporateeurope.org/power-lobbies/2015/09/alter-eu-decade-campaigning-transparency-ethics-accountability-and-democracy

- 83. Search here for past events: http://cepr.org/active/meetings/pastmeetings.php.

- 84. http://corporateeurope.org/trade/2013/09/busting-myths-transparency-around-eu-us-trade-deal

- 85. Following a reader's comment, we would like to clarify that Mr. Goldschmidt was Director at Goldman Sachs from 1970-1985, after which he worked as a financial consultant in London and Monaco. In 1993 he became the Director of the Financial Operations Service within DG ECFIN (Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs) at the Commission (Source: http://www.theglobalist.com/contributors/paul-goldschmidt/). Since his retirement from the Commission in 2002, Mr Goldsmith has regularly written about political and financial topics.

- 86. http://alter-eu.org/sites/default/files/documents/ALTER-EU's%20own%20consultation%20response.pdf

Comments

Re Thomas More Institute you state "The Advisory Board includes Paul Goldschmidt, Director at Goldman Sachs International in London and Head of the Financial Transactions section within DG ECFIN." According to his publicly available LinkedIn entry Paul Goldschmidt ceased work as an 'administrateur' for Goldman Sachs in March 1985, over 23 years ago, and retired from the European Commission in 2002, 14 years ago. I find the implication that Mr Goldschmidt remains connected to either or both these institutions more than a decade or two decades ago quite misleading and undermines trust in many of your other suggested influences. Propose that you correct the reference to Mr Goldschmidt's previous affiliations by noting the dates when he left both places.