Toxic residues through the back door

Pesticide corporations and trade partners pressured EU to allow banned substances in imported crops

Pesticide corporations and trade partners have put immense pressure on the EU to allow residues of certain hazardous pesticides - banned in Europe - to be present in food and feed imports. Facing an endless number of visits, letters and reports, complaints and threats at the WTO by the US, Canada and others, the European Commission dropped its original plan to ban residues of these dangerous chemical substances in imports. It is now up to the new Commission - with its ambitious European Green Deal - to change this approach and stand up for public health.

EU pesticide rules include a ban on particularly hazardous substances in pesticides, for instance those that are carcinogens or endocrine disruptors. These substances are so dangerous that EU regulators believe that, unlike other chemicals, there is no safe level of exposure to them.

Documents obtained by Corporate Europe Observatory from the European Commission through Freedom of Information laws show how pesticide corporations and trade partners have put immense pressure on the Commission to weaken its approach to these pesticides when it comes to imported food and feed. Facing an endless number of visits, letters and reports, complaints and threats at the WTO by the US, Canada and others, the EU dropped its original plan to ban residues of these substances in imports in order to avoid consumers from being exposed.

Pesticide producers like Bayer-Monsanto, BASF and Syngenta, as well as third countries like the US and Canada, have fought the EU pesticide rules tooth and nail; with some success. The alleged negative impacts of these regulations on international trade have been a key weapon used to fight against the EU’s plan to ban these products, laid out via the so-called hazard-based criteria. These criteria aim to ban particularly dangerous substances, such as carcinogens and endocrine disruptors, from pesticides that end up in the food chain.

With new US-EU talks in the picture, and ongoing debates about the CETA and MERCOSUR free trade agremeents, EU pesticide standards are once again in the firing line.

At the same time, the European Commission was also undertaking a so-called REFIT evaluation of two pesticide regulations that govern pesticide authorisations and residue levels in food. REFIT is part of the EU’s so-called Better Regulation agenda, which in fact generally seems to be focused on making EU regulations ‘better’ for industry.

The final pesticide REFIT report is to be launched at the end of March 2020, at the same time as the new Farm to Fork strategy. It is expected to finally bring clarity about the Commission’s intentions when it comes to toxic pesticide residues in imported goods. On the one hand, Health Commissioner Stella Kyriakides , who is responsible for policy in this area, has recently launched a ‘Beat Cancer Plan’ and is very concerned about the health impacts of pesticides. Trade Commissioner Phil Hogan has, on the contrary, suggested that pesticide standards can be part of a new attempt to reach a US-EU trade deal.

If it is confirmed that the new proposal will allow residues of hazardous pesticides in imports, this would breach the EU’s own health protection goals. It would also see European farmers confronted with unfair double standards, and ignore key demands made by the European Parliament last year. Indeed it would undermine the new Commission’s own stated ambitions for the Green New Deal and the Farm to Fork strategy, before they have even taken off. Those plans contain significant promises of reduced pesticide use and more sustainable imports.

Pesticides: The difference between EU and other regulatory systems

The EU has very different rules to regulate the sale and use of pesticides from those in the US or Brazil. The 2009 EU pesticide regulation established ‘hazard-based cut-off criteria’ for particularly dangerous substances such as carcinogens and endocrine disruptors. Pesticides identified as such have to be banned because it is scientifically established that some chemicals do not have a safe level of exposure. This is the case for instance with some carcinogenic, mutagenic and reprotoxic chemicals (CMR) as well as endocrine disruptors. The chemical industry lobby as well as trade partners like the US have always strongly opposed the hazard-based approach and favoured a risk-based approach, claiming that a safe level of exposure can always be established (“the dose makes the poison”). (See 2015 report A Toxic Affair by Stéphane Horel and CEO.)

Pesticides that do not meet the hazard-based cut-off criteria will be subjected to the usual EU risk assessment. It should be noted that a risk assessment can of course also lead to a ban, if risks are found to be too great. As a result of these differences, a 2015 report by the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) listed 82 pesticides that are banned in the EU but approved in the US. According an industry law firm, over a quarter of the pesticides used in the US are not approved in the EU, including the herbicide atrazine and beekillers clothianidin, thiamethoxam and - for most uses - imidacloprid. The same law firm recalled how Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro, within the first 100 days of his presidency, gave the green light for 152 pesticides, previously banned in Brazil. Work published by Professor Larissa Bombardi of the University of São Paulo highlights the fact that out of 504 active pesticide ingredients authorised in Brazil, 149 are prohibited in the EU.

Public concern about health and environmental impacts of pesticides, however, will put strong pressure on the new EU Commission to take action to reduce their use. Von der Leyen’s European Green Deal explicitly calls for “an increased level of ambition to reduce significantly the use and risk of chemical pesticides”.

REFIT: a threat to public interest health regulation?

In 2016 the European Commission launched a so-called REFIT evaluation on the Pesticide Regulation (1107/2009) and the Maximum Residue Legislation Regulation (396/2005). REFIT (Regulatory Fitness and Performance programme) is part of the EU’s Better Regulation Agenda, whose main purpose is to alleviate the regulatory burden for business.

Indeed, REFIT presented another opportunity for industry to attack the new hazard-based criteria, as it could potentially lead to the EU pesticide regulation being opened up for renegotiation. On several occasions when industry complained about the EU’s hazard-based approach for pesticides, the Commission pointed to the REFIT evaluation. Moreover, when Canada brought up the hazard-based approach in the context of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), the Commission recommended that Canadian actors participate in the REFIT process.

On several occasions when industry complained about the EU’s hazard-based approach for pesticides, the Commission pointed to the REFIT evaluation.

The pesticide industry took up the Commission’s invite, and weighed in heavily on the REFIT evaluation. Pesticide Action Network (PAN) Europe has observed how the questions asked in the REFIT consultation were strongly biased towards finding out how burdensome the regulations are for industry interests, rather than their usefulness for health and the environment.

Pesticide corporations also lobbied the Commission directly on the REFIT evaluation. For instance, in February 2018, lobby consultancy firm European Public Policy Advisors (EPPA) wrote to Internal Market and Industry Commissioner Bienkowska’s cabinet that, “given our strong experience as advisors to Bayer”, they would like to advise DG GROW on how the legislation should be changed “to increase the competitiveness of European companies such as Bayer, the world market leader”.

Toxic residue levels in imported goods - a thorny trade issue

The pesticide industry’s fight against the hazard-based cut-off criteria is well known, but there is also an elephant in the room, as yet unacknowledged: Can food still be exported to the EU if it contains residues of pesticides that fall under these criteria, ie that are, for instance, carcinogenic or reprotoxic? If not, that would mean that these pesticides can no longer be used on crops destined for the EU market.

This was the topic of a two-day workshop on pesticide residues held in October 2016 by the European Crop Protection Association (ECPA), the pesticide industry’s lobby group, which was attended by officials from DG SANTE and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). In a follow up report, ECPA said that for some sectors “this issue is their biggest policy challenge at present, and is having a significant impact on predictability and on trade”.

The issue was raised again when, in February 2017, two agricultural attachés from the US Mission to the EU visited DG SANTE. In March that year, a Bayer lobbyist visited a cabinet member of Phil Hogan, then EU Agriculture Commissioner, sharing concerns about how the EU would deal with maximum residue levels on imported goods - the so-called import tolerances - for hazardous pesticides. Bayer told the EU official that they expected the Commission to operate “in compliance with WTO obligations to avoid trade distortions”.

Bayer told the EU official that they expected the Commission to operate “in compliance with WTO obligations to avoid trade distortions”.

Two days later, two Bayer lobbyists met with Nathalie Chaze, a cabinet member of the Health and Consumer Commissioner Vytenis Andriukaitis, and again asked about the EU approach. Ms Chaze replied that the objective of the EU rules was “to protect consumers against cut-off substances and their residues in food, again independently of their origin”. This answer clearly did not please the Bayer lobbyists, who replied that this would “not only affect their business in the EU but also in third countries exporting to the EU”. They also said that this would be challenged at the WTO.

The World Trade Organisation (WTO) allows members to challenge a policy measure or safety standard introduced by another country via a WTO dispute. For example, the US took a case against the EU for its ban on hormone-treated beef. Nevertheless countries are still permitted to set higher standards than those agreed in certain international settings, “if there is scientific justification”. In spite of this, the disciplining power of the threat of a trade dispute is significant, in particular for DG Trade.

In June 2017 another trade partner knocked on the doors of DG Trade to raise concerns over pesticide residues. This time it was the Canadian mission to the EU, along with Cereals Canada, a lobby group that, beyond cereal producers, also counts Bayer, BASF, Corteva (Dow/Dupont) and Cargill among its members. They expressed great concern about glyphosate or other pesticides getting banned, and the problems that would pose in adhering to maximum residue level requirements.

They made the point that the maximum residue level regulation, unlike the pesticide regulation, does not explicitly mention the hazard-based criteria. Therefore, they argued, there was no legal basis for banning the presence of hazardous substances in residues on imported crops.

On 12 and 13 June 2017, the increasingly controversial issue was on the agenda of an important EU expert committee. EU Member State experts gathered in Brussels for a meeting of the Standing Committee on Plants, Animals, Food and Feed (SCOPAFF). In this meeting, DG SANTE made it clear: the existing residue levels for hazardous pesticides banned by the EU would be deleted and brought to the limit of detection (LOD) – meaning that residues on imported products would not be allowed from the level at which they can be detected. New requests for import tolerances (the specific maximum permitted residue levels for other less dangerous chemicals in imports) would be refused. The Commission’s Legal Service provided advice supporting this approach. As DG SANTE later explained to ECPA, exceptions would only be made in case of a ‘serious threat to plant health’. In that case, a temporary MRL could be set, which would also apply to imports.

The entire pesticide lobby promptly jumped into action mode.

The Commission stands its ground

On 10 July, ECPA’s chief lobbyist Euros Jones wrote to Klaus Berend, head of the Commission’s pesticide unit at DG SANTE. He wrote that the opinion of the Commission’s Legal Service was “surprising” and “not in line with the EU’s legislative and international obligations”. He added that “in a world where the production and supply of food and feed are largely globalised, the setting of import tolerances is vital as part of the internationally agreed rules to govern their trade”.

He feared that lowering import tolerances to the limit of detection would mean that “growers in third countries would no longer be able to export to the EU some of the food and feed they produce”. He said it was “illogical” to automatically refuse import tolerances and demanded they should be set “regardless of whether a substance is approved in the EU or not”.

He emphasised: “Given such a substantial potential impact, we believe that the EU’s Better Regulation principles should apply to such a measure - and this should include a full socio-economic impact assessment of the proposed measure.”

The next day Jones wrote another letter, this time to high-level officials at DG GROW, Joaquim Nunes de Almeida and Carlo Pettinelli. Jones repeated the message that “trading partners worldwide would be deeply concerned if classified products could no longer be traded with the EU due to hazard-based restrictions”.

“Trading partners worldwide would be deeply concerned if classified products could no longer be traded with the EU due to hazard-based restrictions” - pesticide lobby group ECPA.

On 10 July 2017, Bayer and Syngenta lobbyists also met personally with Health Commissioner Andriukaitis and his staff, and urged him to change his mind. But Commissioner Andriukaitis made it very clear that if substances meet the hazard-based cut-off criteria, “accepting MRLs higher than the limit of detection would constitute unacceptable risks to human health”. A day later BASF met with DG SANTE officials, raising the same objections, but the Commission defended its approach.

Industry lobby intensifies

Bayer and Syngenta then took it to the next level. Erik Fyrwald and Liam Condon, Chief Executive Officers of Syngenta and Bayer respectively, immediately penned a letter to Commissioner Andriukaitis, not hiding their fury: “Hazard-based cut-offs should not be used by the EU to introduce trade barriers or satisfy political objectives. It's important that we all work to counter emotive messaging used by some groups and explain that hazard does not equate to risk. (…) As you may recall, our key concern is the increasingly conservative, politically-driven, hazard-based control system in Europe.”

In September 2017 ECPA took the issue to the Secretariat General, warning them of significant trade impacts, “which raises some questions of Better Regulation”. In fact, the EU ‘Better Regulation’ agenda functions in practice as a deregulation agenda. It is used to weaken and abolish current rules, while significantly hampering, or even preventing, the introduction of new ones.

The first stakeholder meeting on the pesticide REFIT, which brought together pesticide corporations, NGOs and member states to discuss an external study that would feed into the evaluation, was also held in September 2017. The objective of that study was, inter alia, “to identify positive or negative trade impacts” stemming from the setting of MRLs and import tolerances.

ECPA visited DG Trade on 27 September 2017, calling for an impact assessment of the proposed new regulation, as well as an assessment of its WTO compatibility. In a follow up email to DG Trade, ECPA drove the messages home once more: import tolerances should be set based on risk assessment, WTO members should be consulted before taking any action, and an impact assessment should be done in line with ‘Better Regulation’. The US Soybean Export Council also paid a visit to DG Trade that same day, to remind them that the EU approach “will very likely lead to trade disruptions”.

Before the next meeting of the SCOPAFF committee of member state experts, on 5 and 6 October 2017, ECPA sent a letter to the participants saying that industry was “extremely concerned” about their previous conclusion. The letter ends by saying that “given the significant impacts of implementing the policy option currently being put forward, the Commission should carry out an impact assessment, in line with the EU’s Interinstitutional Agreement on Better Law making”. They also presented a legal argument saying that not setting import tolerances for hazardous pesticides would violate WTO rules.

Scaremongering via claims of trade losses

In October 2017 ECPA again brought regulators from the Commission, Member States and EFSA together for another pesticide residue workshop, co-organised by FoodDrinkEurope. The chair for the day was Rob Mason, an employee of product defense company Exponent. These types of companies often work for corporations to collect or manufacture evidence to defend their products and keep them on the market.

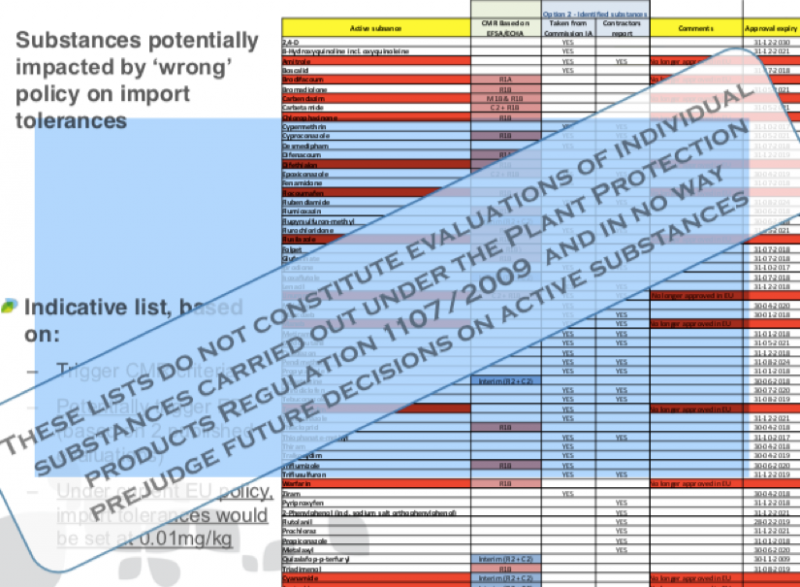

At the workshop ECPA lobbyist Euros Jones presented a list of substances “potentially impacted by ‘wrong’ policy on import tolerance” (see image), while at the same time trying to make sure not to imply that these substances actually were hazardous.

Source: ECPA website, accessed 9 February 2020

On 15 November 2017 Bayer and DTB Associates Consulting, a US lobby outfit whose clients include Monsanto, Bayer, Croplife US and biotech lobby group BIO, met with DG Trade. Bayer presented a report funded by Croplife International and ECPA as ‘evidence’ of the claimed future trade disruptions. The report, titled ‘Estimation of Affected Imports through Hazard Criteria’, was prepared by consultancy firm Bryant Christie and provided truly bloody figures of alleged economic losses; often an effective lobby instrument.

The basis for the report was a list of 58 pesticides, identified by ECPA itself, that they estimated would be classified by the EU as hazardous, and could thus be banned. Bryant Christie then made an estimation of the trade volume of goods that might contain traces of these pesticides, and their value. Agricultural imports with a total value of no less than €70 billion, they claimed, could be adversely affected by the loss of pesticide maximum residue levels for these 58 hazardous substances. Bryant Christie estimated that this represented “over sixty per cent of the estimated total value of all agricultural imports to the EU in 2016”.

Agricultural imports with a total value of no less than €70 billion could be adversely affected by the loss of pesticide maximum residue levels for 58 hazardous substances. - Bryant Christie report for ECPA

Bayer and its consultants told DG Trade that potentially affected commodities would include commodities “not produced in the EU”, including fruits, nuts, oilseeds, groundnuts, coffee, tea, spices and animal feed.

The outcome of this analysis was a double-edged sword for industry, to say the least. On the one hand, it produced shocking figures, a useful lobby instrument. On the other hand, going public with the findings could make it seem like the pesticide industry itself admitted that over sixty per cent of all agricultural products imported into the EU might contain residues of hazardous pesticides having mutagenic, reprotoxic, carcinogenic or hormone-disrupting properties.

Bryant Christie, however, made a very important disclaimer at the beginning of their report, noting that their analysis provided an estimation of trade flows that “could potentially be affected”, but “not a prediction of the likely trade effects”. Indeed, no trade effects would occur if producers made the necessary changes, by ceasing to use these hazardous pesticides. Ultimately, it is quite normal for countries to demand that imported goods meet their safety standards.

The US government seemed to use the very same figures when it, along with Australia, submitted a complaint to the WTO in November 2017 against the EU for trying to regulate endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Their statement said that a 2016 “independent analysis" estimated global trade damage at over $75 billion, and damage to US exports specifically at nearly $5 billion. According to a trade media outlet, the US issued a statement saying that “producers are concerned that they will no longer be able to export products to the EU if MRLs for banned substances are set at default levels”.

CETA kicks in, the EU backtracks

By December 2017 it appeared that lobby efforts were succeeding, and the Commission was starting to backtrack. In a meeting at the premises of the big grain traders lobby group COCERAL, DG SANTE responded to their concerns, stating that “.. after discussions with Member States on the initial proposal, and in the light of the reactions from stakeholders and third countries, further reflections were ongoing in view of defining a Commission approach”.

This meant that the pressure exerted by the US and Canada, pesticide lobbyists and a cohort of member states was starting to have an effect, and that the Commission was considering doing a u-turn and allowing toxic residues on imported goods. The glyphosate controversy – that came to its climax with a final vote in December 2017 – may be the cause that this shift went rather unnoticed.

In meetings with BASF and the US Soybean Export Council in March and April the following year, the Commission again confirmed that it was further reflecting and working on a “WTO-compatible solution”.

In fact, on 26 and 27 March 2018 important talks between the EU and Canada were held in Ottawa in the context of the CETA deal. Documents released to the Council of Canadians following Freedom of Information requests show that pesticide residue levels were a key issue for a specific joint committee on food standards.

Shockingly, on pages 166 and 167 of the meeting report, under ‘Goals and Outcomes’, it is stated that “the long-term goal is for the EU to move away from a hazard-based cut-off criteria as a basis for regulatory decisions” [sic]. The document adds that if the hazard-based criteria remained in place, this would jeopardise €1.9 billion in Canadian exports.

Another conclusion was that “advocacy efforts” would be made to influence the EU deliberations on import tolerances. Notably a ‘recommended point’ was included which stated that Canada “seeks concrete assurance from the EU that decisions on setting MRLs and import tolerances will continue to be made” on the basis of the risk assessment approach, rather than the hazard-based approach.

The Council of Canadians and Foodwatch Netherlands published a report on these revealing CETA documents 12 February 2020, ahead of a crucial vote on the ratification of this trade deal in the Dutch Parliament.

The CETA meeting was clearly very significant in the EU’s decision to weaken its approach. Some months later, when Canada, the US and a number of other countries wrote to ask Health Commissioner Andriukaitis what the state of affairs was, in June 2018, the response confirmed that the Commission had abandoned its original approach.

Andriukaitis wrote back that “after taking into account the concerns raised by stakeholders, Member States, and third countries”, products banned according to the hazard-based criteria would undergo a risk assessment as described in the MRL Regulation. In other words, the Commission had caved to industry and trade pressure.

This new proposal would mean that import tolerances for hazardous pesticides would be allowed, and that European citizens would be exposed to these residues, often unbeknownst to them.

This new proposal would mean that import tolerances for hazardous pesticides would be allowed, and that European citizens would be exposed to these residues, often unbeknownst to them.

Back in Brussels, on to Montreal

On 3 July 2018, a couple of DG SANTE officials faced a large group of lobbyists, representing no less than twenty four lobby associations, combined in yet another lobby platform, the Agri-Food Chain coalition. They included lobbyists representing seed companies (Euroseeds), pesticides (ECPA), flower producers (Union Fleurs), potatoes (Europatat), animal feed (FEFAC), food and drinks (FoodDrinkEurope), fruit and vegetables (FRESHFEL), and so on. The officials had a tough time. They noted that the atmosphere of the meeting was “rather tense”, with a lot of criticism directed towards the Commission regarding the hazard-based approach to pesticide regulation and its alleged impact on international trade.

Perhaps it thus came as a surprise to the lobbyist crowd that SANTE actually had good news for them: in fact, a new approach had been agreed with Member States, and the risk assessment procedure set out in the maximum residue level regulation would be followed for these residues. This, they said, was “in line with the WTO/SPS agreement and responds to concerns from third countries”.

On 26 September 2018 a high-level CETA meeting took place, for which then Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström and a large delegation of officials travelled to Montreal. The new, more business-friendly approach on pesticide residues featured in one of the briefings prepared for Malmström by her cabinet. It was there in black and white: import tolerances can also be requested “for active substances falling under the hazard-based cut-off criteria of the EU legislation”. This message was from now on actively communicated to European producers and the pesticide lobby, as well as to trade partners.

Later that autumn DG SANTE updated the technical guidelines for setting pesticide residue levels accordingly, saying that MRLs set as import tolerances would not have to be deleted after a product is banned, “provided that they are acceptable with regard to consumer safety as confirmed by a full and recent EFSA risk assessment”.

Importantly however, this decision has never been endorsed by Member States nor by the full College of Commissioners.

Business applauds

A high-level official of DG Agriculture traveled to the US in December 2018 to discuss trade issues with the US Department of Agriculture and the US Trade Representation. In his luggage was a briefing with the same message. But this briefing also pointed out the painful inconsistency of this new position with EU health protection goals, when noting that “the intrinsic properties (hazards) specified in the cut-off criteria [..] are so severe that the EU legislators considered that any exposure to such substances leads to unacceptable risk”.

As a defensive argument, the agriculture official was advised to warn his US counterparts that “in the current political climate that is highly sensitised to pesticide-related issues it would be counterproductive to discuss this issue in bilateral negotiations with the US, as this will be interpreted as another attempt to undermine the high level of protection for health and environment in the EU”.

But what was the need to “discuss” the issue in bilateral talks if the EU had already given up on this high level of protection?

Indeed, US exporters were applauding. On 23 January 2019, the US Soybean Export Council again visited the premises of DG Trade, welcoming the shift as “a positive development from trade angle”.

US exporters were applauding. On 23 January 2019, the US Soybean Export Council again visited the premises of DG Trade, welcoming the shift as “a positive development from trade angle”.

One week earlier, however, an overwhelming majority of the European Parliament had voted in favour of proposals made by the Special Committee on the European Union’s authorisation procedure for pesticides (PEST). This committee had been set up on 6 February 2018, following the glyphosate controversy. The members demanded a high level of protection against the use of hazardous pesticides, including in the case of imports, as well as a level playing field for European farmers. This was precisely the opposite of what EU Comission officials had conceded to.

Lowering ambitions: Still not weak enough?

Yet there was more to come. DG SANTE official Anne Bucher sent a note to her boss, the Head of Cabinet Arunas Vinciunas. She recalled how six months earlier seven EU Member States - Austria, Germany, Lithuania, Poland, the Netherlands, Portugal and the UK - objected even to the weakened approach, and wanted “an exclusively risk-based approach”. SidenoteIndeed, according to an email to DG SANTE, seen by CEO, the Dutch government had already told DG SANTE in March 2017 that it favoured an approach whereby “the setting of import tolerances for a substance which would fall under a hazard based cut off criteria [..] should be possible”.

Bucher also mentioned the pressure from “numerous interventions on this topic in the WTO-SPS Committee” which could lead to a formal WTO dispute, adding that this issue also remained “a particularly difficult point in EU-US relations”.

Therefore she proposed another adjustment, which would allow for a transition period which would maintain MRLs for hazardous pesticides until the new import tolerances had been finalised. She acknowledged that this too would meet with opposition.

As the official noted, the new package would not be to the liking of the European Parliament, as it went against the recommendations of the PEST committee. European farmers organisations too would be opposed to increased discrimination, which would occur if there were different standards imposed on EU and non-EU producers. Indeed, farmers organisations La Via Campesina and COPA have strongly opposed trade deals like MERCOSUR that will allow more produce onto the European market that have not been produced respecting the same standards.

For obvious reasons Bucher expected that DG Trade, on the other hand, would “strongly support” this proposal. She did warn that DG Agriculture might oppose it, although, she added,“DG Agriculture has never before opposed similar situations when substances were banned in the EU, but still used in third countries and allowed in residues”.

Member states should be the first to be informed of this latest adjustment, Bucher wrote, and then the proposal should be “carefully communicated to third countries and stakeholders”.

On Monday 25 March 2019, Arunas Vinciunas responded: “We have a difficult political choice to make as either, on the one hand, the EP and EU farming community or, on the other hand, third countries and several MS will be unhappy with our approach. This reflects the increasingly difficult task we are facing when setting MRLs on the basis of the current legislation”.

He reminded her that the hazard-based cut-off criteria were established as an acknowledgment that such chemicals are too dangerous to be used on food, based upon their classification. Despite this, Vinciunas concluded that they could nevertheless “reluctantly agree” to import tolerances being established on the basis of a risk assessment. However the Commissioner would not agree to adding a transition period for these substances, since “this would amount to lowering further our level of ambition in relation to the protection of public health”.

More trade partner aggression

A few months later it appeared that the EU’s weakened approach still did not go far enough to satisfy the US. In July 2019 the US and fifteen other countries attacked the EU pesticide policy at the WTO, arguing that “the EU is unilaterally attempting to impose its own domestic regulatory approach onto its trading partners”.

The US and fifteen other countries attacked the EU pesticide policy at the WTO, arguing that “the EU is unilaterally attempting to impose its own domestic regulatory approach onto its trading partners”.

The alliance of countries called on the EU to stop “unnecessarily and inappropriately” restricting trade, and instead “to use internationally accepted methods of setting tolerance levels”. Here they were referring to the residue levels set by the Codex Alimentarius, which is intended to facilitate international trade. Codex residue levels are often higher than those in the EU and long-banned toxic substances like DDT and Paraquat still feature in the Codex list.

In their communication to the WTO these countries demanded a risk assessment approach be used for import tolerances, as well as additional transition periods.

Commission’s legal opinion favoured pro-health approach: access denied

Corporate Europe Observatory sent questions about this matter to DG SANTE’s Head of the Pesticide Unit in January 2020. He responded that “work is still ongoing” on how to set import tolerances for these substances, and that “internal discussions” are still taking place on risk management. Berend clarified that, at this point, from a legal perspective, “.. the submission of an import tolerance request remains possible even for substances meeting the cut-off criteria”. This, he explained, is because “such substances are not excluded by the MRL regulation”.

This is what industry had been arguing repeatedly as well. However, the earlier legal opinion by the Commission’s own Legal Service had reached a different legal conclusion, favouring the Commission’s original plan for a hazard-based approach. This service's legal advice is precisely intended to underpin the legality of the Commission's decisions, in particular to reduce the risk of subsequent litigation. It would have been illuminating to see the legal arguments put forward in this opinion, both regarding the MRL regulation not mentioning the hazard-based criteria, and regarding the question of WTO-compliance. But the European Commission is keeping this document secret. The head of unit explained that such opinions “are internal to the Commission and therefore considered protected”.

Now what? Ambitious green goals vs concessions in the name of ‘free trade’

The coming two months will be decisive. A final decision was so far never endorsed by the EU Member States nor by the full Commisison. Now new Commissioners are in charge and they are in the position to change the position again.

The REFIT evaluation is now expected to be publicly released at the end of March, at the same time as the new Farm to Fork strategy. This report is the most likely source of a concrete proposal from the Commission on pesticide residues.

In light of this, the announcement by Commission President Ursula von der Leyen that an EU-US trade deal could be reached “within a few weeks” was ominous. Trade Commissioner Phil Hogan added further oil to the fire with some very provocative statements: he told lobby group BusinessEurope that an EU-US deal could be reached by slashing “regulatory barriers in agriculture”. The US Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue explicitly called on the EU to soften limits on pesticide residues.

If the REFIT report does indeed contain the weak approach outlined in the documents discussed above, this will immediately call into question the new Commission’s ambitious European Green Deal and Farm to Fork strategy.

If the REFIT report does indeed contain the weak approach outlined in the documents discussed above, this will immediately call into question the new Commission’s ambitious European Green Deal and Farm to Fork strategy.

Indeed, the Green Deal explicitly calls for “an increased level of ambition to reduce significantly the use and risk of chemical pesticides”. A weakening of the EU’s public health regulation would also undermine the credibility of Health Commissioner Stella Kyriakides’ own Beating Cancer Plan. Moreover the new EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030, yet to be released, may even propose a 50 per cent reduction in pesticide use by 2030, according to ENDS Europe.

Indeed, in view of the climate and biodiversity crises, urgent action is needed to reduce pesticide use. A coalition of European organisations have launched a new European Citizens’ Initiative calling for an 80 per cent reduction of pesticide use by 2030, with a full phase-out by 2035.

This issue is now in the hands of Health Commissioner Stella Kyriakides. It is her responsibility to protect EU citizens from being exposed to toxic residues in imported food. She would be wise to bear in mind that watering down key food safety standards within the EU will not go down well at all. Not with numerous EU Member States and the European Parliament, nor with European farmers, civil society organisations and the public.