One Treaty to rule them all

The Energy Charter Treaty and the power it gives corporations to halt the energy transition

A new report from CEO and TNI exposes how the little-known Energy Charter Treaty gives corporations the power to obstruct the transition from climate-wrecking fossil fuels towards renewable energy. And how it is being expanded, threatening to bind yet more countries to corporate-friendly energy policies.

Read the full report in English or in Spanish.

A summary is also available in English, French, German, Spanish, Italian, and Arabic.

More about the key findings can be found on energy-charter-dirty-secrets.org.

Two decades ago, and without significant public debate, an obscure international agreement entered into force, the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT). It acts like the secret magical “One Ring to rule them all” from the Lord of the Rings trilogy, granting corporations enormous powers over our energy systems including the ability to sue governments, which could obstruct the transition from climate-wrecking fossil fuels towards renewable energy. And the ECT is in the process of expansion, threatening to bind yet more countries to corporate-friendly energy policies.

Today the ECT applies to nearly 50 countries stretching from Western Europe through Central Asia to Japan. Among its many provisions, those regarding foreign investments in the energy sector – also known under the infamous acronym ISDS or investor-state dispute settlement – are the ECT’s cornerstone. The ECT’s ISDS provisions give foreign investors in the energy sector sweeping rights to directly sue states in international tribunals of three private lawyers, the arbitrators. Companies can be awarded dizzying sums in compensation for government actions that have allegedly damaged their investments, either directly through ‘expropriation’ or indirectly through regulations of virtually any kind. Energy giant Vattenfall, for example, has sued Germany over environmental restrictions on a coal-fired power plant and for phasing out nuclear power. Oil and gas company Rockhopper is suing Italy over a ban on offshore oil drilling. Several utility companies are pursuing the EU’s poorest member state, Bulgaria, after the government reduced soaring electricity costs for consumers.

Yet the ECT and its profiteers have largely escaped public attention. While the past decade has seen a storm of opposition to ISDS in other international trade and investment deals the ECT has managed to steer surprisingly clear of this public outrage. Many investor lawsuits under the treaty remain secret. For others, there is only scant information available. And in countries in the process of acceding to the ECT, hardly anyone seems to have even heard of the agreement, let alone have thoroughly examined its political, legal, and financial risks.

This report shines a light on the “one ring” of the ECT, which will greatly influence the battle over our future energy systems, as well as the corporations and lawyers, to which it grants enormous powers.

Key findings

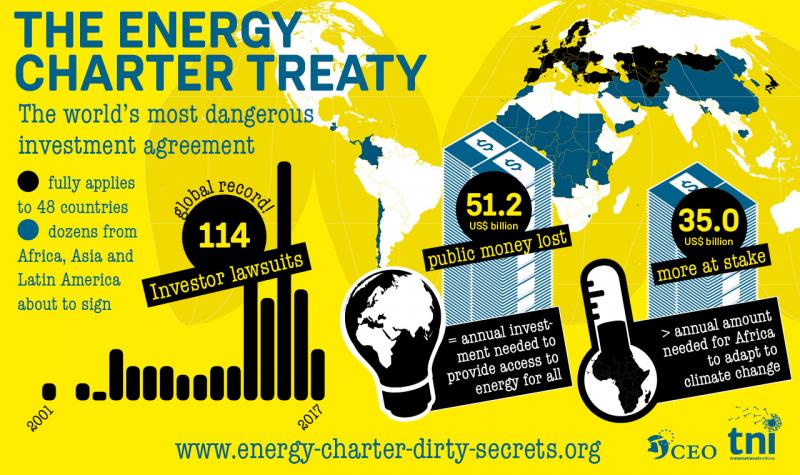

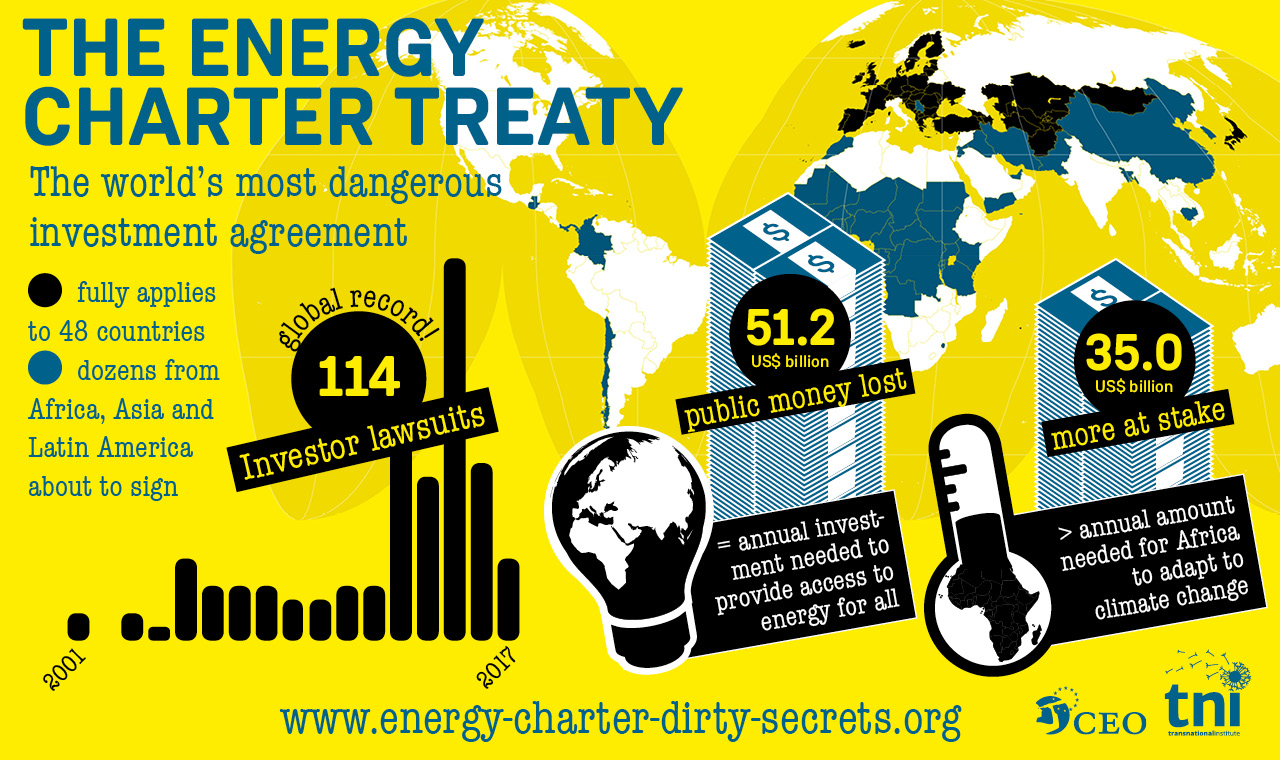

- No trade and investment agreement anywhere in the world has triggered more investor-state lawsuits than the ECT. At the time of going to press in June 2018, the ECT Secretariat listed a total of 114 corporate claims filed under the treaty. Given the opacity of the system, the actual number of ECT claims could be much higher.

- In recent years the number of ECT investor lawsuits has exploded. While just 19 cases were registered during the first 10 years of the agreement (1998-2008), 75 investor lawsuits were filed in the last five years alone (2013-2017).* This trend is likely to continue.

- More recently, investors have begun to use the ECT to sue countries in Western Europe. While in the first 15 years of the agreement 89 per cent of ECT-lawsuits hit states in Central and Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, today Spain and Italy head the list of the most-sued countries. The ECT remains the only effective treaty in which Western European states have accepted ISDS with countries that are also capital exporters to them. It is also the only agreement which allows for investor-state arbitrations against the EU as a whole.

- More and more money is at stake for states and taxpayers. There are 16 ECT suits in which investors – mostly large corporations or very wealthy individuals – sued for US$1 billion or more in damages.* Some of the most expensive claims in the history of ISDS include ECT cases such as Vattenfall’s challenge to Germany over its exit from nuclear power (over US$5.1 billion), and the largest ISDS award ever, a US$50 billion order against Russia in the Yukos cases. Total legal costs average US$11 million in ISDS disputes, but can be much higher.

- Corporations claim compensation for loss of ‘future profits’. Oil company Rockhopper is not just claiming the US$40-50 million from Italy which it actually spent on exploring an oil field in the Adriatic Sea. It also claims an additional US$200-300 million for hypothetical profits the field could have made had Italy not banned new oil and gas projects off the coast.

- Governments have been ordered or agreed to pay more than US$51.2 billion in damages from the public purse* – roughly equalling the annual investment needed to provide access to energy for all those people in the world who currently lack it. Outstanding ECT claims* have a collective value of US$35 billion – far more than the estimated annual amount of money needed for Africa to adapt to climate change.

- Investors who have filed lawsuits under the ECT come mostly from Western Europe. Companies and individuals registered in the Netherlands, Germany, Luxembourg, and the UK (or in the tax haven Cyprus) make up 60 per cent of the 150 investors involved in claims.*

- The majority of ECT claims are intra-EU disputes, yet sideline EU courts. 67 per cent of ECT investor lawsuits* were brought by an investor from one EU member state against the government of another member state, claiming large sums of public money arguably not available to them under the EU legal system. That means that nearly half of all known intra-EU investment disputes were launched under the ECT (the others being based on bilateral treaties). In March 2018 the European Court of Justice ruled that intra-EU ISDS proceedings under these bilateral treaties violate EU law as they sideline EU courts – an argument which could also apply to the ECT.

- The ECT is prone to abuse by letterbox companies, which mainly exist on paper and are often used for tax evasion and money laundering. For example 23 of the 24 “Dutch” investors who have filed ECT-lawsuits* are letterbox companies. They include Khan Netherlands (used by Canadian mining company Khan Resources to sue Mongolia even though Canada is not even a party to the ECT), and Isolux Infrastructure Netherlands and Charanne (both used by Spanish businessmen Luis Delso and José Gomis, two of the richest Spaniards, to sue Spain). Thanks to the ECT’s overly broad definition of “investor” and “investment”, states can effectively be sued by investors from around the globe, including by their own nationals.

- The ECT is increasingly being used by speculative financial investors such as portfolio investors and holding companies. In 88 per cent of lawsuits over cuts to support schemes for renewable energy in Spain, the claimant is not a renewable energy firm, but an equity fund or other type of financial investor, often with links to the coal, oil, gas, and nuclear industries. Several of the funds only invested when Spain was already in full-blown economic crisis mode and some changes to the support schemes had already been made (which the funds later argued undermined their profit expectations). Some investors view the ECT not only as an insurance policy, but as an additional source of profit.

- The ECT is a powerful tool in the hands of big oil, gas, and coal companies to discourage governments from transitioning to clean energy. They have used the ECT and other investment deals to challenge oil drilling bans, the rejection of pipelines, taxes on fossil fuels, and moratoria on and phase-outs of controversial types of energy. Corporations have also used the ECT to bully decision-makers into submission. Vattenfall’s €1.4 billion legal attack on environmental standards for a coal-fired power plant in Germany forced the local government to relax the regulations to settle the case.

- The ECT can be used to attack governments that aim to reduce energy poverty and make electricity affordable. Under the ECT Bulgaria and Hungary have already been sued for compensation in the hundreds of millions, in part for curbing big energy’s profits and pushing for lower electricity prices. Investment lawyers are considering similar action against the UK, where the government has proposed a cap on energy prices to end rip-off bills.

- A small number of arbitrators dominate ECT decisionmaking. 25 arbitrators have captured the decisionmaking in 44 per cent of the ECT cases while two-thirds of these super-arbitrators have also acted as legal counsel in other investment treaty disputes. Acting as arbitrator and lawyer in different cases has led to growing concerns over conflicts of interest, particularly because this small group of lawyers have secured extremely corporatefriendly interpretations of the ECT, paving the way for even more expensive claims against states in the future.

- Five elite law firms have been involved in nearly half of all known ECT investor lawsuits. Law firms have been key drivers of the surge in ECT cases, relentlessly advertising the treaty’s vast litigation options to their corporate clients, encouraging them to sue countries.

- Third party funders are becoming more and more established in ECT arbitrations. These investment funds finance the legal costs in investor-state disputes in exchange for a share in any granted award or settlement. This is likely to further fuel the boom in arbitrations, increase costs for cash-strapped governments, and make them more likely to cave in to corporate demands.

- There are concerns about self-dealing and institutionalised corruption in institutions that administer ECT disputes. For example the Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce (SCC), prominent in ECT disputes, is problematic because its arbitrations are particularly secretive, prone to conflicts of interest, and potentially more biased against states than other proceedings.

- Polluting companies and for-profit investment lawyers enjoy privileged access to the ECT Secretariat, which puts into question the latter’s neutrality and ability to act in the interest of the ECT’s signatory states as well as a transition off fossil fuels. More than 80 per cent of the companies on the ECT’s Industry Advisory Panel make money with oil, gas, and coal. Two thirds of the lawyers on the ECT’s Legal Advisory Task Force have a financial stake in investor lawsuits against states. Both advisory groups are given ample opportunities to influence the Secretariat, ECT member states, and the wider Charter process in their own interest. Several high-ranking officials at the ECT Secretariat were with arbitration law firms before and/or after they worked at the Secretariat.

- Many countries across the world are about to join the ECT, threatening to bind them into corporate-friendly energy policies. Jordan, Yemen, Burundi, and Mauritania are most advanced in the accession process (ratifying the ECT internally). Next in line is Pakistan (where investment arbitration is controversial, but which has already been invited to accede to the ECT), followed by a number of countries in different stages of preparing their accession reports (Serbia, Morocco, Swaziland – renamed eSwatini in April 2018 –, Chad, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Colombia, Niger, Gambia, Uganda, Nigeria, and Guatemala). Many more countries have signed the non-binding International Energy Charter political declaration, which is considered the first step towards accession to the legally binding Energy Charter Treaty.

- There is an alarming lack of awareness about the ECT’s political and financial risks in the ECT’s potential new signatory states. Officials from ministries with experience in negotiating investment treaties and defending investor-state arbitrations are largely absent from the process, which is being led by energy ministries. This is worrying as many of these countries already have disastrous experience with investor lawsuits under other investment agreements, which could multiply if they sign on to the ECT.

- The expansion process is aggressively promoted by the ECT Secretariat, the EU, and the arbitration industry, who are eager to gain access to the rich energy resources in the global South and to expand their own power and profit opportunities. While they downplay or dismiss the risks to states of acceding to the ECT, they promote the agreement as a necessary condition for the attraction of foreign investment, and in particular clean energy investment for all. But there is currently no evidence that the agreement helps to reduce energy poverty and facilitate investment, let alone investment into renewable energy.

But there is some good news. Around the world, the tide is turning against ECT-style super-rights for corporations. Campaigners, activists, academics, and parliamentarians are beginning to ask critical questions about the ECT. The agreements and the investor lawsuits it has enabled could also come under legal fire from EU courts. More countries could follow the example of Russia and Italy, which have already turned their back on the ECT.

This report warns of the dangers of expanding the ECT to an ever-growing number of countries and concludes with eight key reasons for leaving – or not joining – the ECT. Just as in the Lord of the Rings, where the “fellowship” of nine companions around the little hobbit Frodo Baggins manages to destroy the One Ring, a fellowship of citizens, legal scholars, parliamentarians, courts and governments might be in the making, which will eventually break the binding power of the ECT “ring”.

* Figures refer to the total ECT cases known about up to the end of 2017. There are likely to be others that, due to secrecy in the claims process, have not come to light.

Read the full report in English or in Spanish.

A summary is also available in English, French, German, Spanish, Italian, and Arabic.

A special website with easy access to some of the key findings is here.