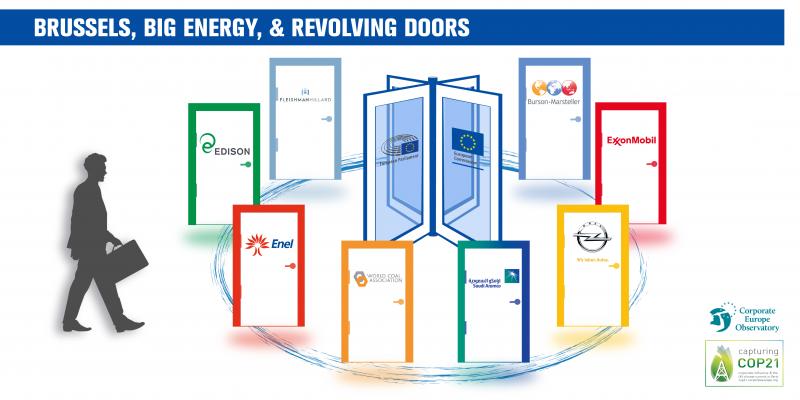

Brussels, big energy, and revolving doors: a hothouse for climate change

As environment and energy ministers prepare to meet in Paris for the COP 21 climate change talks, CEO takes a look at how the revolving door ensures that the EU institutions remain close to Big Energy.

Summary

The climate cooks while the Big Energy lobby continues to walk the EU's corridors of power, pushing its arguments that it needs to be at the negotiating table and that a combination of unsustainable techno-fixes and copious greenwash will provide the answer to runaway climate change.

The climate cooks while the Big Energy lobby continues to walk the EU's corridors of power, pushing its arguments that it needs to be at the negotiating table and that a combination of unsustainable techno-fixes and copious greenwash will provide the answer to runaway climate change.

Elsewhere Corporate Europe Observatory has documented the bag of tricks of the corporate climate lobbyist. We have shown that for decades these companies have been lobbying against effective climate action at national, EU, and international levels, obstructing policies that would effectively cut emissions and leave fossil fuels in the ground.

In this article, we explore one specific tool of the energy lobbyist, namely recruitment through Brussels' revolving door. The revolving door between the EU institutions and Big Energy demonstrates the corporate capture of the EU decision-making process (which is supposed to operate in the public interest) by industry agendas. EU institutions turn a blind eye to the pro-corporate culture, networks, mind-set, and bias that such individuals might bring, as well as to possible conflicts of interest which could see Big Energy benefiting from the know-how and contact books of insiders. It is clear that the European institutions' current revolving door rules are not strong enough to eliminate the risk of conflicts of interest, and corporate capture, arising.

This report focuses on five cases:

- The Commission official: Marcus Lippold used to work at ExxonMobil, a company well-known for funding climate denial and blocking climate change policies; then he went to work for DG Energy where he was responsible for cooperation with OPEC. Now he is on sabbatical from the Commission and working for Saudi Aramco, the world's biggest oil and gas company which is owned by Saudi Arabia, a country which has been blocking action on climate change for years.

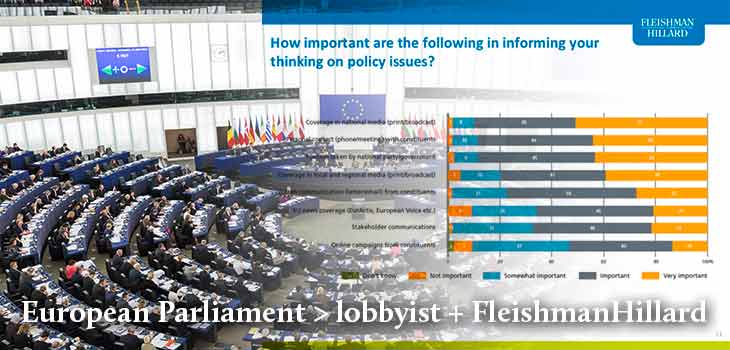

- The MEP: Chris Davies MEP championed carbon capture and storage (CCS) while spending 15 years on the European Parliament's environment committee, working closely with Big Energy interests to do so. Now he has set up his own environmental lobby consultancy and is working with FleishmanHillard, one of Brussels' biggest lobby firms.

- The commissioner: Joaquín Almunia the former Barroso II competition commissioner, has been a paid member of the "scientific committee" to produce the study entitled 'Building the Energy Union to Fuel European Growth'. The report was written by a for-profit consultancy and commissioned by (and likely funded by) Enel.

- The Commission special adviser: Nathalie Tocci is the special adviser to High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice-President of the European Commission Federica Mogherini but is simultaneously on the board of “Europe's oldest energy company” Edison, owned by French energy giant EDF.

- The member state official: Matthew Hinde was Head of EU Strategy at the UK government's Department of Energy and Climate Change for the past two years but has now joined the Brussels office of lobby firm FleishmanHillard, one of the leading PR specialists in energy, whose clients include Total, Shell, Statoil, ENI, SHV Energy, Exxon Mobil, BP among others, to act as its Head of Energy Practice.

In the annex, further climate and energy-related revolving doors cases are explored. You can also read this report in Espanol. Our press release is available here.

The Commission official: Marcus Lippold

The Commission official: Marcus Lippold

In a shocking revolving doors case, DG Energy official Marcus Lippold is currently enjoying an officially-authorised sabbatical with Saudi Aramco, the world's biggest oil and gas company. Saudi Aramco is the state-owned oil company of Saudi Arabia with interests in petroleum and chemicals. Saudi Arabia has a destructive track-record at UN climate talks, currently arguing to water-down an agreement at the climate talks in Paris in December 2015. The company says that it maintains the world’s largest spare crude oil production capacity, equating to one in every eight barrels produced. Lippold is currently responsible for Aramco's regional corporate planning and policy in Europe and Russia, since he joined in April 2015.

It is highly likely that Lippold, while wearing his DG Energy hat, would have come into contact with Aramco. After all, he had been responsible for the coordination of bilateral oil dialogues and cooperation with OPEC and he had a “special focus on energy dialogue” with the OPEC Secretariat: Gulf Cooperation Council, International Energy Forum, Saudi Arabia. Prior to this role, he was in the Commission as senior energy economist working on several directives (the emissions' trading scheme's cap and trade, renewable energy directive, fuels quality directive, energy taxation directive etc), according to his LinkedIn profile.

Aramco's board comprises figures from the Saudi regime as well as Sir Mark Moody-Stuart, former chairman of Shell; Peter Woicke, former Managing Director of the World Bank; and Andrew Gould, chairman of the BG Group plc. Aramco is not in the EU lobby register. (You can read CEO's exposé of EU lobby firms who act for repressive regimes, including some members of the Gulf Cooperation Council, here.) In October 2015, Saudi Aramco joined with other Big Energy corporations to call for “an effective climate change agreement at COP21”. However, a look behind the rhetoric shows that in fact it represents a self-interested call for more emphasis on gas and projects on carbon capture and storage.

The Commission was apparently happy to authorise this sabbatical, so long as Lippold abides by “certain limited conditions”, although it wouldn't tell us what these were. This reflects a totally blasé approach to possible conflicts of interest. Lippold's Commission authorisation for this post runs until the end of March 2016, which is safely after the COP21 UN climate negotiations to be held in Paris in December 2015.

In fact, this is Lippold's second sabbatical from the Commission. Before he joined Aramco, in August 2013 he became Vice President for business strategy and corporate affairs (responsible for the group upstream/ midstream/ downstream strategic projects and the management of governmental and international institutional relations) at MOL Group. MOL Group describes itself as a leading oil and gas corporation based in central and eastern Europe. It says it has operations in over 40 countries and it is owned by a variety of interests: the Hungarian state, ING bank, CEZ (the Czech electricity group) and OmanOil all have shareholdings.

MOL is in the EU lobby register and it says it is active in “all files related to energy, climate, environment, taxation, transport, competition, company law”. It records six full-time lobbyists and a 2013 lobby expenditure of €300,000-€399,999. According to intergritywatch.eu, in May 2015 MOL group met with Bernd Biervert (the Deputy Head of cabinet of Maroš Šefčovič, the commissioner responsible for the Energy Union) to present the company's activities in Central and Eastern Europe.

MOL group is a member of major energy industry lobby groups who are active at the EU level: FuelsEurope, the International Association of Oil & Gas Producers (IOGP), the European Chemical Industry Council (CEFIC), the European Petroleum Refiners Association, and the European Round Table of industrialists. MOL is also a client of the lobby consultancy firm FIPRA.

Lippold will have had contact with MOL group during his time at the Commission. In 2011, he moderated a speakers' panel at the European Fuels Conference which included a speaker from MOL. And now we know that Lippold has had contact with the Commission on behalf of MOL since he went on sabbatical, in correspondence that should be defined as 'lobbying'. In December 2013, Lippold wrote to an official in DG Energy about the implementation of the oil stocks directive (which places requirements on member states to maintain a certain level of oil reserves) in Poland. The official replies that “the Commission does not assess and discuss national draft legislations”. However, once the Polish authorities finalise the legislation, the Commission will carry out a “conformity check” and the official says that it will “keep your remarks in mind”.

In June 2014, Lippold, again on behalf of MOL, wrote again to DG Energy, this time to a head of unit, regarding the implementation of the same directive in Romania. It contains criticism of the Romanian government's implementation of the directive and the “large financial burdens for fuel suppliers” which have apparently resulted. Lippold sets out MOL's position at length and then asks for the Commission’s understanding of how the directive should be implemented (delegated) at the national level, which is duly provided.

In January 2014, new revolving door rules for EU officials came into force. For the first time, those on sabbatical were forbidden from “engaging in an occupational activity, whether gainful or not, which involves lobbying or advocacy vis-à-vis his institution and which could lead to the existence or possibility of a conflict with the legitimate interests of the institution” (see article 40). And yet, Lippold, on sabbatical, has apparently been able to lobby former DG on behalf of private (MOL) interests. Either way, the Commission's willingness to authorise this sabbatical, albeit under “certain limited conditions”, indicates how blinkered its approach to conflicts of interest and corporate capture really is.

In December 2013, MOL launched a case against the Croatian government at the international arbitration court, the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). Even though he only joined MOL in August 2013, it seems inconceivable that Lippold in his role as Vice President for business strategy and corporate affairs (which included the management of governmental and international institutional relations), did not play some part in this process. So Lippold, who can return to DG Energy at any point from his sabbatical, has been working for a corporation which has sued an EU member state government!

Lippold's sabbatical placements with Saudi Aramco and MOL group are part of his career pattern. Before he joined the Commission in 2008, he had had a long employment history with ExxonMobil which he has documented on his LinkedIn profile and which we have previously assessed on RevolvingDoorWatch. ExxonMobil's climate track record is appalling, considering its consistent attacks on climate science, its funding of climate denial (despite it's own scientists warning of risks of climate change since 1970s) and its lobbying to block effective action.

In our view, the Commission has taken a totally irresponsible approach to the risk of conflicts of interest during Lippold's coming and goings through the revolving door. When Lippold first joined the Commission from ExxonMobil in 2008, it felt that his experience in the oil industry was “an asset for DG ENER”. This is remarkable, as was the authorisation of his subsequent sabbaticals. The fact that a Commission official working on energy policy can leave one day and then start to work for a major EU energy company the next day beggars belief. That he can then go to work for the biggest oil company in the world, while maintaining a 'right to return' to the Commission shows how far the EU executive will go to accommodate the demands of Big Energy.

Lippold did not respond to efforts to contact him via Saudi Aramco. You can read the profiles of Lippold on RevolvingDoorWatch here and here.

Read about other Commission officials in the annex.

The MEP: Chris Davies

The MEP: Chris Davies

Chris Davies was a prominent Liberal Democrat MEP until he lost his seat in the 2014 European elections. He was a member of the committee on Environment, Public Health and Consumer Policy (ENVI) for the full 15 years of his career as an MEP. The ENVI committee is influential in the development of all EU environmental regulations; it is where reports are drafted, amendments made, text changed, and compromises made.

Davies is an ardent supporter of action to tackle climate change. He is also widely known as a strong advocate of carbon capture and storage (CCS), an experimental technology that seeks to bury the carbon dioxide produced from the fossil fuels used in electricity generation and industrial processes. CCS attracts the support of many major energy companies, as a look at the membership list of the Carbon Capture and Storage Association indicates: BP, Chevron, E.on, Engie, Shell and Statoil. Another pro-CCS lobby group, the Zero Emissions Platform (ZEP), reflects a similar corporate membership. Industry has been especially keen to attract public funding for CCS technology. However, the technology is controversial with many who point out that it is risky, expensive and could lead to further fossil fuel use and dependency. Even its proponents admit the technology won't be commercially viable before 2030, even with massive injections of public funding so, at a time when serious action to stop runaway climate change is needed within 10 years, CCS only offers to lock in more fossil fuel use and divert funding away from sorely needed investments in renewables and other real solutions.

Davies was the ENVI rapporteur for the CCS Directive in 2008, and according to his Liberal Democrat profile, he “played a key role in introducing the principal funding mechanism used to support development of CCS demonstration projects”. Since then, millions of euros of public EU funds have been channelled into CCS, including into the Ciuden CCS project in Spain. This project was backed by Endesa, Spain's largest electricity company, which is owned by the Italian energy giant Enel. Yet this project has now been cancelled; the initial work was completed but it will not “proceed to full-scale demonstration”.

A 2010 report by Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO) and Spinwatch on the battle to fund CCS exposes the corporate support for Davies' pro-CCS activities. The report showed that Shell, BP, Zero Emissions Platform, Climate Change Capital, Eurelectric and Alstom acted as Davies' advisers on CCS: he strategised with them and even co-drafted amendments with them. In the end, Davies told the European Commission that if they didn't agree to his proposals around public subsidies for CCS demonstration projects, he would block all progress on the dossier, telling fellow MEPs that he was "blackmailing" the Commission.

His 2012 report on the Roadmap for moving to a competitive low carbon economy in 2050 also banged the drum for CCS. It criticised the procedural delays and financial shortfalls for new CCS projects, as well as the “lack of commitment on the part of certain Member States” and called upon the Commission to publish a CCS action plan.

In 2013-14, he was rapporteur on a further report on developing and applying carbon capture and storage technology in Europe which called on the Commission to create an EU industrial innovation investment fund to support the CCS flagship projects, and suggested that this could be financed from the sale of allowances from the EU's controversial emission trading scheme, a core CCS industry demand.

Now the former MEP has set up his own political and environmental consultancy. According to information on the EU lobby register for Chris Davies Ltd, his consultancy works on “Energy and climate policy, including carbon capture and storage (CCS); environment and sustainability policy, including circular economy issues. Fisheries policy”.

Davies lists three clients (FleishmanHillard, Lexmark International, European Climate Foundation), each of whom provide the consultancy with €10,000-€24,999 lobby revenue in the present year. FleishmanHillard is one of Brussels' biggest lobby firms and its energy-related clients include Total, Shell, Statoil, ENI, SHV Energy, Exxon Mobil, BP. FleishmanHillard does not provide a list of the EU legislative dossiers that it work on for clients (as required by the lobby register rules) although it does make clear that it works in the area of environment and energy policy. It spends over six million euros a year on lobbying activities and lists over 45 European parliament pass-holders. With such a rollcall of energy companies on its client list, it is not hard to imagine why FleishmanHillard considers Davies to be an asset.

The lobby register entry of Lexmark International (the printing and IT company) shows that its interest are in “Waste legislation, Circular economy, Copyright, Energy efficiency, Anti-counterfeiting and clones, Data Protection, Cyber Security, Cloud, Standards and eHealth”. It spent €300,000-€399,999 on lobbying in 2014. Davies' third client is the not-for-profit European Climate Foundation.

In response to questions from Corporate Europe Observatory, Davies told us that he had done “absolutely no work on CCS for Fleishman Hillard” and his only payment from his knowledge of CCS was for an article written for the Global Carbon Capture and Storage Institute earlier in 2015. But after 15 years of being a key figure on the ENVI committee, public relations firms and industry are likely to be interested in hiring Davies not just on CCS but also on a wider range of other issues, also relating to climate, energy and environment.

Davies told CEO that he complies with the requirements of the EU's lobby register. This illustrates one of a range of flaws with the EU's lobby disclosure rules: there is no requirement to provide precise information about specific lobbying work for clients. Furthermore, there are next to no revolving door requirements on former MEPs; they are free to set up lobby consultancies as soon as they leave office, despite the obvious risk that this could lead to private interests gaining substantial benefit from an ex-MEP's time in public office.

Davies' replies can be read here and his full RevolvingDoorWatch profile is available here.

Read about other MEPs in the annex.

The Commissioner: Joaquín Almunia

The Commissioner: Joaquín Almunia

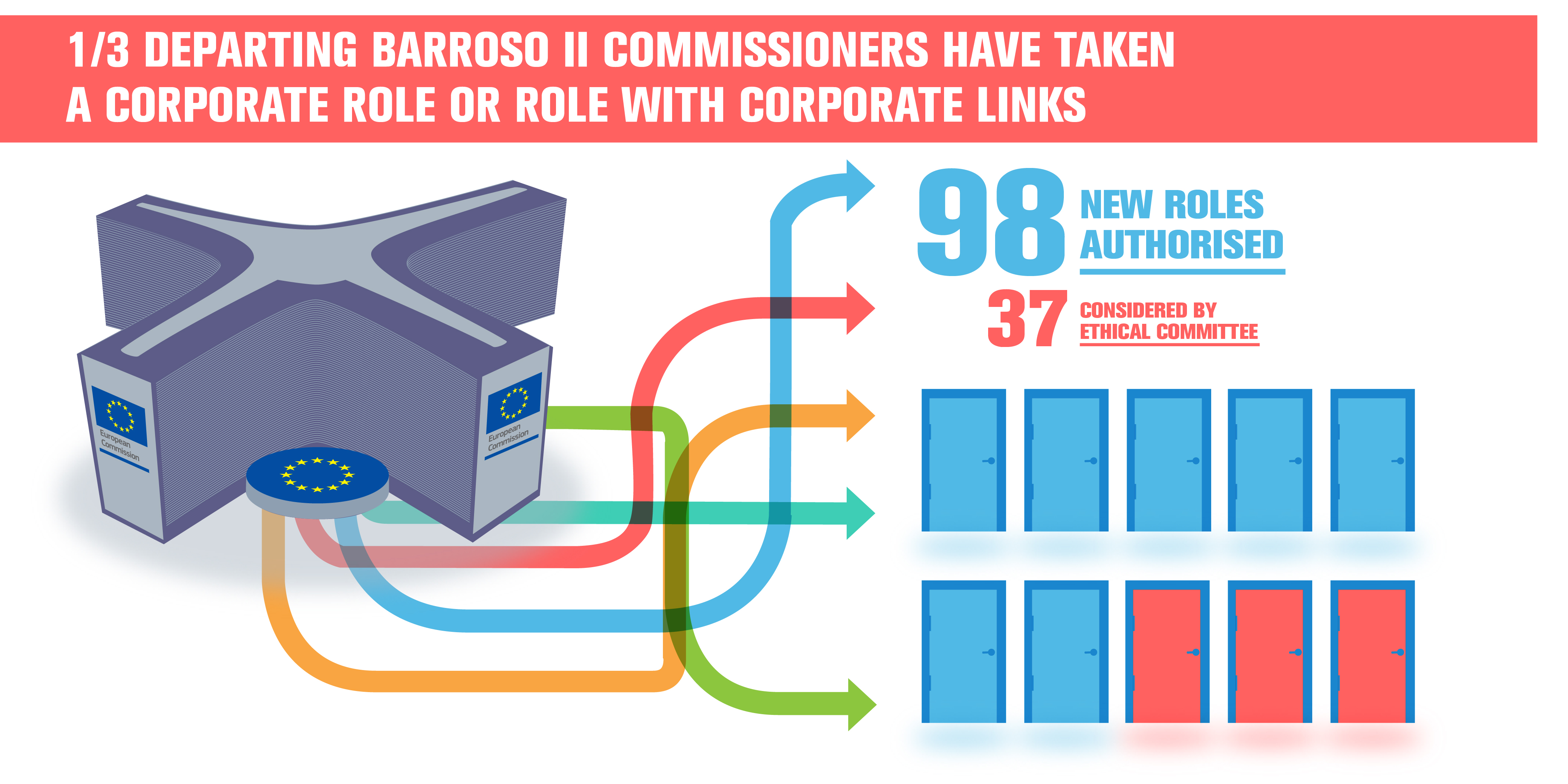

Commissioners, at the top of the influence tree in Brussels, must abide by a (weak) code of conduct, and for the 18 months after they have left office, they must apply to the Commission for authorisation for any new “professional activities”. (You can read our recent report on the revolving door moves of the Barroso II Commission here).

Among the 13 roles for which ex-Competition Commissioner Joaquín Almunia has received Commission authorisation is as a paid member of the scientific committee to produce the study "Building the Energy Union to Fuel European Growth" by the European House-Ambrosetti. The latter is a for-profit consultancy based in Italy and its board includes senior staff from Enel, ING bank, JP Morgan and others. In fact the Energy Union study was “requested” by (and is presumably funded by) Enel, the major Italian multinational operating in the power and gas markets. Enel has its logo on the study and shares the copyright; the advisory board for the study included several Enel staff including Francesco Starace, the Chief Executive, and Simone Mori, Head of European affairs, plus three other staffers. Commissioning third parties to undertake research and policy work in an area where they wish to boost their strategic influence is a common way for corporations to promote their agenda.

Overall, the focus of the report is on energy for competitiveness, which is very much the line of heavy industry lobbies including the chemicals lobby and BusinessEurope (where Enel is a partner) who argue that cheap fossil fuel energy is needed to keep their members in business and stop companies from moving their production abroad to countries with less ambitious climate measures (so called carbon leakage).

Almunia's own preface to the report talks about how to improve competitiveness. He says: “We need to achieve the single market for electricity and gas, through interconnections, common regulations and adequate incentives for investors.” Yet this implies that we need to build new infrastructure for fossil fuels which lock us into long-term use, while “incentives for investors” means public money to “leverage” ie subsidise dirty energy / infrastructure companies to help achieve this. In fact we should be moving away from such fuels and into community-owned renewables and energy-efficient buildings instead.

While the report supports the move to decarbonisation of the EU's energy system by 2050 (an oft-stated EU goal which has not been followed up by meaningful policies), its policy recommendations appear to be more in tune with Enel's interests: a single market for energy (which would make it easier for big energy companies to operate across borders), and a stronger emissions trading scheme. Enel is especially keen on the latter as it will make natural gas more competitive with coal, and Enel is heavily investing in gas. The report also promotes the myth that there can be clean fossil fuel generation and talks up the “opportunity” of shale gas.

Others on the board for the study included Jean-Arnold Vinois, a former director of the internal energy market unit at DG Energy (2011-12) who then went on to be special adviser to then energy commissioner Günther Oettinger (2013-14).

The Energy Union is one of the main priorities of Juncker's Commission. While Vice President Maroš Šefčovič leads, Cañete and several other commissioners are also active on this agenda. It is clear from published lists of meetings and CEO's recent analysis that the Energy Union is attracting a huge number of meetings from industry lobbyists. Not surprisingly, they wish to shape the policy to their own ends, including in the area of the liberalisation of the EU's energy market, something that Enel and other energy utilities are hugely interested in.

Enel is a major EU lobbyist spending over €2,000,000 in 2014. Since December 2014, Enel has met top officials in the Commission at least six times (according to IntegrityWatch), including a meeting with Vice-President Maroš Šefčovič who is responsible for the EU's Energy union. The Guardian recently reported Enel's promise that, while coal currently generates 29 per cent of the electricity it supplies, the company would not build any new coal plants, saying they are “basically technologically obsolete”. However, InfluenceMap, an online tool which rates a company's climate lobbying record says Enel's “support for, and engagement with, climate legislation appears inconsistent, and at times contradictory. They appear to have an ambiguous position on energy efficiency standards and renewable energy legislation, expressing support on their corporate news site and opposing legislative measures, such as the EU 2030 targets, in consultation and in media sources.” InfluenceMap's rating of Enel implies that the company says one thing in public, but provides a rather different message behind the scenes.

Enel's lobbyingIn December 2014, CEO wrote the following about Enel's lobbying:

|

When it was asked to authorise Almunia's role on this study, the Commission's Ad hoc Ethical Committee said the study may “provide a useful contribution to EU endeavours”. The Commission approved Almunia's paid role in this study as long as he did not “favour the commercial interests of the companies involved”. But this is rather meaningless considering that Enel commissioned, and likely paid for, the study and has its logo all over it. The Commission should have taken a far more sceptical view about this role and the automatic benefits likely to accrue to Enel from having an ex-commissioner endorsing the study.

The Commission Special Adviser: Nathalie Tocci

The Commission Special Adviser: Nathalie Tocci

Nathalie Tocci, the Special Adviser to High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy/Vice-President of the European Commission Federicia Mogherini, is at the same time a paid, independent member of the board of “Europe's oldest energy company” Edison, which is now owned by French energy giant EDF. Tocci's role as a paid special adviser to the European Commission is to provide outreach to think tanks and coordination of work on a new European Security Strategy, beginning with the 2015 Strategic Review. Energy security is recognised as part of the overall EU security agenda, and Vice-President Mogherini leads the Commission's project team "Europe in the World" which includes the commissioner for climate action and energy. In fact there will be an event (Tocci told us that she planne to be present) to look at energy issues in the context of the development of the wider strategy on 1 December 2015.

Edison is a significant EU lobbying organisation, reporting a 2014 lobby spend of €300,000 -€399,999. Edison has an office in Brussels and it has been active and successful in securing meetings with the top echelons of the Commission. According to Integritywatch, since December 2014, it has held at least three lobby meetings, including one with the External Action Service, namely Arianna Vannini from Vice-President Mogherini's cabinet. The meeting was held in January 2015 and was on the topic of “the importance of the Juncker Investment plan for the energy sector”.

Edison is now part of the EDF group. EDF is also a prolific lobbyist, with a 2014 lobby spend of €2,500,000-€2,999,999; according to Integritywatch, it has secured at least seven lobby meetings with the top of the Commission since December 2014. InfluenceMap, an online tool which rates a company's climate lobbying record says of EDF: “[its] messaging appears to demonstrate positive engagement with climate change related regulations and policies, however their engagement with policy makers seems to be more negative”. InfluenceMap questions EDF's commitment to renewable energy and energy efficiency targets which seem to be “inconsistent”, alongside their membership of several lobby groups opposed to climate action.

The Commission saw no problem in appointing Tocci as a special adviser to a European commissioner, despite her role as a board member of Edison; in fact Ms Tocci has told us that the Commission did not even raise the matter with her. Tocci told us that she did not see any conflict of interest as Edison was not involved in her work on the EU security strategy. She says she is not part of Edison's lobbying work in Brussels and that as an independent board member, she is not part of Edison's decision-making.

However, CEO has concerns about this. The fact that a special adviser who is simultaneously a paid board member at a major energy company can be appointed without question, indicates how blasé the Commission is about corporate power and its close proximity to EU decision-making. CEO has submitted a complaint to the Commission about its handling of the possible conflicts of interest arising from the situation of Tocci; the reply was disappointing and showed the Commission's weak approach to conflicts of interest. The Commission's rules for special advisers can be read here.

Read about another Commission special adviser in the annex.

The member state official: Matthew Hinde

The member state official: Matthew Hinde

Matthew Hinde was Head of EU Strategy at the UK government's Department of Energy and Climate Change for the past two years until September 2015; just a few weeks later he joined FleishmanHillard Brussels, one of the EU's biggest lobby consultancies as Senior Vice-President and Head of its energy practice. FleishmanHillard is a power player in the energy lobbying field and its clients include some of the world's major energy companies: Total, Shell, Statoil, ENI, SHV Energy, ExxonMobil, BP, and many others with an interest in energy and / or climate policy. It spends over six million euros a year on lobbying activities and lists over 45 European parliament pass-holders, now including Hinde himself.

Hinde is likely to know his way around Brussels well, having previously served as energy attaché at the UK permanent representation 2009-2013 and FleishmanHillard has not been shy at trumpeting Hinde's revolving door credentials saying he “offers a wealth of experience in EU energy issues from his time in the UK civil service”.

The UK plays a key role in EU policy-making. It has a lot of weight in energy negotiations and is very active in championing industry interests in CCS, nuclear, and other areas that are likely to be of interest to clients that FleishmanHillard represents. FleishmanHillard says Hinde was “instrumental in key EU energy policy dossiers, including the 2030 Climate and Energy Framework and the Energy Union”.

Hinde himself will be advising clients directly including, it seems, on the issues he handled until the month previously for the UK government. Specifically he has said: “With the Energy Union approaching its first anniversary and many of its key legislative files starting, there’s never been a more important time for energy companies to engage with Brussels. I am looking forward to helping them navigate this changing policy environment at a time of business disruption for many industry players.” FleishmanHillard says that Hinde will also work on the “impact of energy policy on energy users in sectors such as chemicals and transportation.” Its clients in those sectors include Monsanto and EasyJet.

In April 2015, whilst representing the UK government, Hinde addressed a FleishmanHillard Brussels event on Diversifying Europe’s Natural Gas Supply, speaking alongside another revolving door-spinner Joachim Balke (see annex of this report). As the event was held under Chatham House rules, we do not know who was present or what was said.

The UK government authorised Hinde's move (under UK business appointment rules) to become a lobbyist but the authorities have steadfastly refused to provide any additional information on the conditions applied to the authorisation despite an appeal under UK freedom of information rules. On the evidence of FleishmanHillard's press release announcing Hinde's arrival, those conditions were not strong.

We contacted Hinde before publishing this report with a variety of questions about his new role. He simply told us: “I undertook the UK Government Advisory Committee on Business Appointments process before leaving DECC. In terms of clients, FleishmanHillard’s are detailed on the EU transparency register.”

Conclusions

It is clear that action is needed to tackle the hothouse of corporate lobbying and ever-spinning revolving doors that Brussels and the EU institutions represent. We propose the following policy recommendations:

|

The urgency to stop runaway climate change requires us to take radical action. Just in the way that the toxic tobacco lobby has been seriously restricted in its possibilities to influence and capture public health decision-making, thanks to the World Health Organisation's article 5.3 and its accompanying guidelines, maybe it is time to implement a similar policy to severely limit or prevent lobbying influence of fossil fuel interests. With only a few years left to us to prevent irreversible global warming, such a step now seems imperative.

The WHO tobacco control guidelinesAmong other measures, the WHO tobacco control guidelines recommend that governments and other public policy-makers: “(2) Establish measures to limit interactions with the tobacco industry and ensure the transparency of those interactions that occur; (3) Reject partnerships and non-binding or non-enforceable agreements with the tobacco industry; (4) Avoid conflicts of interest for government officials and employees; (6) Denormalize and, to the extent possible, regulate activities described as “socially responsible” by the tobacco industry, including but not limited to activities described as “corporate social responsibility”; (7) Do not give preferential treatment to the tobacco industry...”. |

Annex

Other MEPs:

Holger Krahmer (ALDE) was active on the environment, public health and food safety (ENVI), the temporary committee on climate change, and as a substitute member of the committee on industry, research and energy. A few months after leaving the Parliament, Krahmer started working for the lobby consultancy firm Hanover Communication. He worked there for six months as a senior adviser on EU policy. In April 2015, Krahmer left Hanover to start working for Opel Group, the European branch of General Motors (GM), as director of European affairs public policy and government relations. According to its entry in the register, in 2014 the group reportedly spent between €900,000 – €999,999 lobbying the European institutions. Since May, Krahmer has been a registered lobbyist with the European Parliament for Opel.

Holger Krahmer (ALDE) was active on the environment, public health and food safety (ENVI), the temporary committee on climate change, and as a substitute member of the committee on industry, research and energy. A few months after leaving the Parliament, Krahmer started working for the lobby consultancy firm Hanover Communication. He worked there for six months as a senior adviser on EU policy. In April 2015, Krahmer left Hanover to start working for Opel Group, the European branch of General Motors (GM), as director of European affairs public policy and government relations. According to its entry in the register, in 2014 the group reportedly spent between €900,000 – €999,999 lobbying the European institutions. Since May, Krahmer has been a registered lobbyist with the European Parliament for Opel.

While an MEP, Krahmer worked extensively on the regulatory environment of the auto industry. Most notably, he was the rapporteur for carbon dioxide emission levels on light commercial vehicles. His report was criticised by civil society organisations and small business associations alike. Car leasing firms and delivery companies claimed that Krahmer's targets would allow vans to continue being energy inefficient, thus failing to significantly reduce CO2 emissions and threatening to increase fuel costs for small and medium enterprises.

Krahmer responded saying: “Laws to reduce the fuel consumption of vehicles are not there to patronise the drivers. It is not the role of the EU to require owners of commercial vehicles that they can only drive up to 120 kilometres per hour and then to say it is a contribution to climate protection.... Besides, this decision is an interference with road traffic regulations of the member states.”

On the other hand, Krahmer's report, and ultimately the Parliament's vote, was welcomed by the European Automobile Manufacturers Associations (ACEA), of which Opel is a member.

The former MEP has been involved with EU climate policy in other ways too. After participating in the temporary committee on climate change, Krahmer contributed to "Inconvenient Truths about Europe’s Climate Policy: suggestions for new liberal approaches”, a report for the ALDE group, where he and other MEPs criticised climate change science and action to tackle climate change.

Opel, and ultimately GM, have a keen interest in overall climate policy and Krahmer's experience is likely to be very valuable to the car company whose lobby targets include “CO2 Emissions Reduction legislation”, “the Euro 6 vehicle emission legislation”, and the fuel quality directive.

But the car-maker also seems to be keen on the emissions trading scheme (ETS). Earlier in the year, the group organised an event in Brussels to discuss future CO2 regulation where arguments were made to extend the ETS scheme to the traffic sector. Several civil society organisations, including CEO, have criticised this scheme for being inherently flawed and incapable of reducing carbon emissions significantly while providing windfall profits to the biggest polluters.

It is expected that GM's, and subsequently Opel's, interest in climate policy will only increase in the run-up to COP 21 in Paris in December. GM sponsored a previous climate conference in Warsaw, something CEO has described as an attempt to 'greenwash' its image.

You can read more about the power of the EU's car lobby here; Krahmer's full RevolvingDoorWatch profile can be read here.

Martin Callanan (ECR) was a member of the Committee on the environment, public health (ENVI) for 13 years, where he produced numerous reports as rapporteur or shadow rapporteur on emission performance standards for new light commercial vehicles, implementation of the Kyoto protocol, the 2030 framework for climate and energy policies, and fluorinated greenhouse gases. Callanan was frequently criticised for his close contacts to industry lobbyists, in particular the car industry.

Martin Callanan (ECR) was a member of the Committee on the environment, public health (ENVI) for 13 years, where he produced numerous reports as rapporteur or shadow rapporteur on emission performance standards for new light commercial vehicles, implementation of the Kyoto protocol, the 2030 framework for climate and energy policies, and fluorinated greenhouse gases. Callanan was frequently criticised for his close contacts to industry lobbyists, in particular the car industry.

He is now a member of the House of Lords (the UK's second chamber) and a consultant to the Symphony Environmental Technologies Group. Symphony's website says that it “specializes in developing and marketing a wide range of plastic products and other environmental technologies, and operates worldwide”. In November 2014, Margrete Auken, a Danish MEP who had been pushing for a ban on oxo-biodegradable plastic bags, accused Symphony of using its links to the UK Conservative-led government to orchestrate a blocking minority against her bag ban in the EU Council of Ministers. Since 1999, the board of Symphony has been chaired by Nirj Deva, another Conservative MEP, who is the subject of significant NGO criticism for his external financial interests.

Symphony is not listed in the EU's lobby register, although it is registered as a client of FleishmanHillard in Brussels. According to his listing in the House of Lords register of members' interests as well as information held by Companies House in the UK, Callanan has set up a company called MC Associates (Europe) Ltd. MC Associates (Europe) Ltd is not registered with the EU lobby register. Clients additionally include EUTOP and the ECR group in the European Parliament. EUTOP is a Berlin-based lobby agency which is not in the EU lobby register but which claims: "Our work is tailored to the European decision-making structures and processes in all their commercial, cultural and political diversity. EUTOP has had a strong network of contacts among political decision-makers in Brussels and selected EU member states for more than 20 years”.

Callanan's full RevolvingDoorWatch profile can be read here.

Eija-Riitta Korhola (EPP) also left the Parliament in 2014 after spending a dozen years on the ENVI committee. She first came to the attention of CEO in 2008 when she and German Christian Democrat MEP Karl Heinz Florenz directly tabled amendments drafted by Eurofer for an important vote in the European Parliament's Environment committee on emissions trading; the amendments were designed to significantly benefit the steel industry. Eurofer is the steel sector trade association whose members include national steel associations and big steel companies such as ArcelorMittal and ThyssenKrupp. What was worse was that the text was actually presented by Florenz as a compromise (usually the result of negotiations among Parliament groups) rather than the views of the affected industry with a huge commercial interest in the vote.

Eija-Riitta Korhola (EPP) also left the Parliament in 2014 after spending a dozen years on the ENVI committee. She first came to the attention of CEO in 2008 when she and German Christian Democrat MEP Karl Heinz Florenz directly tabled amendments drafted by Eurofer for an important vote in the European Parliament's Environment committee on emissions trading; the amendments were designed to significantly benefit the steel industry. Eurofer is the steel sector trade association whose members include national steel associations and big steel companies such as ArcelorMittal and ThyssenKrupp. What was worse was that the text was actually presented by Florenz as a compromise (usually the result of negotiations among Parliament groups) rather than the views of the affected industry with a huge commercial interest in the vote.

Korhola has now set up something called Korhola Global. Little information is available online about its activities, although Korhola's LinkedIn profile says that it works on consulting and communication on “European matters, energy and environment, human rights & conflicts”. In an email to CEO, Korhola implied that the company would not be active until “my transitional period is over”. She says her new work will be similar to her activities before she joined the Parliament.

In September 2015, it was announced by Dutch private equity company Momentum Capital that Korhola would become a board member of its company Clean Electricity Generation (CEG). CEG is a company producing bio coal technology; bio coal is like charcoal, and in our view, a false techno-fix to the crisis of climate change. While biomass advocates argue that it will be carbon neutral, others point that on a large scale it is far from carbon neutral, as demand for biofuel crops can drive deforestation, land disturbance and often leads to increased fertiliser use, as well as other negative impacts. At Momentum, Korhola will advise both CEG and Seaborough (an LED lighting company) who are part of Momentum Capital’s so-called “clean tech portfolio”.

At the time of her appointment, Martijn van Rheenen, the CEO of Momentum Capital said: “We are delighted to have appointed someone of Eija-Riitta Korhola’s caliber and standing. Her vast knowledge of the energy industry combined with her policy making and legislation track record in the European political arena will be a valuable addition to our team, as we continue to align our European energy related business plan and take our strategy forward.” None of these companies are in the EU lobby register.

Other Commission Special Advisers

Guy Lentz, the Special Adviser to climate action commissioner Cañete is simultaneously a paid member of the board of Enovos Luxembourg, and he also works for Luxembourg's Economic Ministry as Coordinator for EU and international energy issues. Previously he worked at Shell for eight years (1993 to 2000).

Guy Lentz, the Special Adviser to climate action commissioner Cañete is simultaneously a paid member of the board of Enovos Luxembourg, and he also works for Luxembourg's Economic Ministry as Coordinator for EU and international energy issues. Previously he worked at Shell for eight years (1993 to 2000).

Enovos, which does not appear in the EU transparency register, is the biggest Luxembourg energy distribution company and it says it is now taking up the position of “one of the major players on select energy markets in Western Europe”. Enovos Luxembourg also operates in Germany, France, and Belgium, and it generates electricity, natural gas and renewable energy for commercial and household consumers. In 2014, its net turnover was €1,777.4 million.

Enovos Luxembourg is wholly owned by Enovos International, which acts as an umbrella for the network manager Creos Luxembourg (which has been active in responding to a Commission consultation on the security of gas supplies). Enovos International is owned 33 per cent by the Luxembourg state and city; more than 55 per cent is owned between the following major energy firms (or subsidiaries): E.ON, RWE Energy, GDF Suez and Ardian. E.ON, RWE and GDF Suez are all significant EU lobbyists on climate and energy matters, and they all figure among the companies which have been meeting with Commissioner Cañete and his Cabinet to discuss issues in which they, and Enovos, have a huge commercial stake.

It is clear that there is a significant overlap between the interests of Enovos and the work of Commissioner Caňete and his team. Mr Lentz's special adviser role is described as “General assistance to the Commissioner on energy issues”. This is very broad and it is hard to believe that the issues of electricity generation, natural gas, and / or renewable energy (which are all of strategic importance to Enovos Luxembourg and the wider group) would not come up. This is perhaps especially relevant now, when among the main dossiers that need to be developed by Commissioner Cañete and his Cabinet are the Energy Union (including the completion of the energy internal market), new electricity market design, and other issues of major importance to Enovos.

The Commission apparently saw no problem in appointing Lentz as special adviser despite his role as board member of Enovos. Cristina Lobillo Borrero, the Head of Cabinet of Cañete, confirms that on the basis of the declaration of activities of Lentz and the sworn statement, that there is no conflict of interests. The only restriction that has been imposed on him refers to his employment for the Luxembourg ministry, not for Enovos: “In the framework of his mandate as Special Advisor, Mr Lentz will not deal with matters which concern specifically Luxembourg or in which the Luxembourgish Government has a particular interest.”

The Commission should have reflected upon Mr Lentz's board membership of Enovos and should have put in place restrictions to prevent any possible risk of conflicts of interest from arising. In fact, there should have been consideration by the Commission as to whether it was even appropriate for a board member of such a corporation to be a special adviser to a commissioner with clear responsibility for climate change and energy issues. CEO has submitted a complaint to the Commission about its handling of the possible conflicts of interest arising from the situation of Lentz; the reply was disappointing and showed the Commission's weak approach to conflicts of interest.

Other Commission officials

Other known revolving door cases involving climate change and environmental policies include the following:

Joachim Balke has spun through the EU revolving door several times. According to information from his LinkedIn profile, after working for four years at the European Parliament (2001-2004) he went to work for German energy giant E.ON as an advisor until 2008 and then he joined the Commission. After three years in DG Taxation, he moved to DG Energy in 2011 and joined the cabinet of Commissioner Cañete in November 2014. There he is trusted with internal energy market electricity, gas supply, regional initiatives and international gas corridors, the energy community, and mainstreaming climate action.

Joachim Balke has spun through the EU revolving door several times. According to information from his LinkedIn profile, after working for four years at the European Parliament (2001-2004) he went to work for German energy giant E.ON as an advisor until 2008 and then he joined the Commission. After three years in DG Taxation, he moved to DG Energy in 2011 and joined the cabinet of Commissioner Cañete in November 2014. There he is trusted with internal energy market electricity, gas supply, regional initiatives and international gas corridors, the energy community, and mainstreaming climate action.

Our access to documents requests reveal that the ongoing relationship of Balke with E.ON seems to be a close and cosy one. Balke has kept up a regular correspondence with E.ON representatives since his time at DG Energy. In several of the emails released to us, different E.ON staff make explicit reference to the fact that Balke is a former colleague when lobbying him. Balke appears to be particularly friendly with Vera Brenzel, now Head of E.ON's EU representation office.

One of the first meetings Cañete had with industry as Commissioner was with the CEO of E.ON. The meeting (on 12 November 2014) was attended also by Brenzel plus Balke and Cristina Lobillo (Head of Cañete's cabinet). As part of the preparation for this meeting, Brenzel sent Balke a document which she asked him to keep to himself. This meeting does not feature on Cañete's list of published meetings (only systematically published from 1 December 2014).

That first meeting is one of many examples. Since 1 December 2014, E.ON has met six times with Cañete's Cabinet, including with the commissioner present at four of these. Balke has met with E.ON more times during his time as a Cañete Cabinet member than any other lobby group. Overall, of the 72 lobby groups that Balke has met from 1 December 2014 to 1 October 2015, only three were with NGOs or trade unions.

The documents also shed some light on just how easy it is for E.ON to get a meeting with Balke. For instance when Balke was working at DG Energy in 2013, prior to becoming a Cabinet member, E.ON's Brenzel sent him an email at 10.58am on 12 June to check if they could meet to discuss an initiative by Tajani (then Enterprise Commissioner who had just created a high level group for the steel industry, something Brenzel thought could also be desirable for the energy utilities sector). The response from Balke came soon after, at 11.26am, offering to meet that same afternoon. At 11.34am, Brenzel informed Balke that she would take a colleague along, and wondered if they should meet at his office. Balke responded at 11.41am to tell her to just come by when she is ready as he will be working until late. These casual email exchanges illustrates the easy access to Balke that E.ON appears to have enjoyed.

According to the EU lobby transparency register, E.ON has 29 people involved in lobbying the EU institutions, and a full-time equivalent of 11. In the year 2014, E.ON declared a lobby expenditure of €2,000,000 -€2,249,999. The company is a member of many lobby groups through which they also influence EU climate and energy policy, among them Eurelectric, Eurogas, Foratom, IETA, European Energy Forum, ERT, CEPs, Friends of the ETS, and the European Wind Industry Association.

E.ON is indeed a big player in EU climate policies, and with a huge stake in the dossiers dealt with by the Cañete and Šefčovič cabinets, namely the Energy Union with the push to complete the internal energy market, new electricity market design, reform of the emissions trading scheme, and the review of the renewables energy and energy-efficiency directives expected next year.

To conclude, the Commission should be more vigilant when officials join the Commission from the private sector. Those joining from corporations can bring preferences and allegiances, even if they no longer have formal ties or an employment relationship, and there is a risk that this contributes to the corporate capture of policy-making. In the interests of independence – and the climate – members of the Cabinet of the commissioner responsible for climate action should not have overly-friendly relationships with Big Energy. We contacted Balke before publishing this profile but the Commission wrote back to say there was no “established legal or administrative obligation to provide you replies to the questions in your message”.

Mårten Westrup originally worked for DG Enterprise as a policy officer and legal officer including assisting in drafting motor vehicle regulations and participating in DG Enterprise's work on competition policy and the automotive industry. He then moved to become an adviser to the Industrial Affairs Committee (climate change) for BusinessEurope, the big business lobby group which according to InfluenceMap has an “obstructive engagement with numerous strands of climate change policy and regulations”. The Commission did not examine Westrup’s job move under the revolving door rules; he was considered exempt as a contract staff member who was deemed to have not had access to “sensitive information” during his time at the European Commission. In 2011 Westrup returned to the Commission (this time DG Energy) to work as a policy officer in the unit handling 'energy policy & monitoring of electricity, gas, coal and oil markets' including the Energy roadmap 2015, an issue of big importance to BusinessEurope. Westrup remains a DG Energy policy officer in the unit entitled energy policy coordination.

Mårten Westrup originally worked for DG Enterprise as a policy officer and legal officer including assisting in drafting motor vehicle regulations and participating in DG Enterprise's work on competition policy and the automotive industry. He then moved to become an adviser to the Industrial Affairs Committee (climate change) for BusinessEurope, the big business lobby group which according to InfluenceMap has an “obstructive engagement with numerous strands of climate change policy and regulations”. The Commission did not examine Westrup’s job move under the revolving door rules; he was considered exempt as a contract staff member who was deemed to have not had access to “sensitive information” during his time at the European Commission. In 2011 Westrup returned to the Commission (this time DG Energy) to work as a policy officer in the unit handling 'energy policy & monitoring of electricity, gas, coal and oil markets' including the Energy roadmap 2015, an issue of big importance to BusinessEurope. Westrup remains a DG Energy policy officer in the unit entitled energy policy coordination.

Westrup's RevolvingDoorWatch profiles are available here and here.

Fanny-Pomme Langue was a policy officer in DG Energy unit "Regulatory policy and promotion of renewable energy". According to her LinkedIn profile, her work included co-managing the drafting of the Commission's report on sustainability requirements for solid/gaseous biomass, and the monitoring of the implementation and compliance with the EU Renewable energy directive. She was in regular contact with major public and private stakeholders. One of these major stakeholders is AEBIOM, the European Biomass Association. AEBIOM describes itself as “the common voice of the European bio-energy sector with the aim to develop the market for sustainable bioenergy, and ensure favourable business conditions for its members”.

Fanny-Pomme Langue was a policy officer in DG Energy unit "Regulatory policy and promotion of renewable energy". According to her LinkedIn profile, her work included co-managing the drafting of the Commission's report on sustainability requirements for solid/gaseous biomass, and the monitoring of the implementation and compliance with the EU Renewable energy directive. She was in regular contact with major public and private stakeholders. One of these major stakeholders is AEBIOM, the European Biomass Association. AEBIOM describes itself as “the common voice of the European bio-energy sector with the aim to develop the market for sustainable bioenergy, and ensure favourable business conditions for its members”.

In 2013 Langue started to work as policy director of AEBIOM where she remains today. Her main tasks include representing “the position and interest of the bio-energy sectors to European Institutions and other European stakeholders”. AEBIOM's entry in the lobby register shows that Langue is an accredited lobbyist to the European Parliament. The Commission did not screen Langue for possible conflicts of interest when she took up her post as a bio-energy lobbyist as she had been a contract agent.

Langue's RevolvingDoorWatch profile is available here.

Poppy Kalesi was one of Chris Davies MEP's researchers who worked with him on CCS issues. In 2008, she moved to DG Energy to work as a policy analyst on the Strategic Energy Technologies (SET-Plan), which included CCS; she also became programme manager on CCS in DG Energy's coal and oil unit, including managing the implementation and performance of the EU's CCS demonstration projects. In 2010, she left the Commission to join Statoil as EU regulatory affairs advisor; Statoil has significant CCS interests. Kalesi left the company in 2014 to become an energy project consultant at the University of Stavanger.

Poppy Kalesi was one of Chris Davies MEP's researchers who worked with him on CCS issues. In 2008, she moved to DG Energy to work as a policy analyst on the Strategic Energy Technologies (SET-Plan), which included CCS; she also became programme manager on CCS in DG Energy's coal and oil unit, including managing the implementation and performance of the EU's CCS demonstration projects. In 2010, she left the Commission to join Statoil as EU regulatory affairs advisor; Statoil has significant CCS interests. Kalesi left the company in 2014 to become an energy project consultant at the University of Stavanger.

Kalesi's RevolvingDoorWatch profile is available here.

Derek Taylor's LinkedIn profile describes his 25 year career at the European Commission as Energy Adviser/ Head of Unit/ Senior Policy Officer specialising in energy issues and international relations. He specifically worked on nuclear issues. After retiring from the Commission in 2009 he set up his own consultancy called DMT Energy. He became a director at Bellona Europa (an environmental NGO with close links to industry) and a Senior Energy Adviser at Burson-Marsteller, one of Brussels' biggest lobby firms. Today BM's clients in the energy field include: ExxonMobil, Westinghouse (nuclear energy technology), and Neste Oil. After he left the Commission, Taylor was also the European representative of the Global Carbon Capture and Storage Institute for two years.

Derek Taylor's LinkedIn profile describes his 25 year career at the European Commission as Energy Adviser/ Head of Unit/ Senior Policy Officer specialising in energy issues and international relations. He specifically worked on nuclear issues. After retiring from the Commission in 2009 he set up his own consultancy called DMT Energy. He became a director at Bellona Europa (an environmental NGO with close links to industry) and a Senior Energy Adviser at Burson-Marsteller, one of Brussels' biggest lobby firms. Today BM's clients in the energy field include: ExxonMobil, Westinghouse (nuclear energy technology), and Neste Oil. After he left the Commission, Taylor was also the European representative of the Global Carbon Capture and Storage Institute for two years.

Taylor was two years late in applying for authorisation to the Commission for his consultancy work. Despite this major breach in the rules, the Commission still authorised the activities.

Taylor's RevolvingDoorWatch profile is available here.

Luc Werring was at DG Transport and Energy for 23 years, latterly as Principal Adviser to the Director-General. While at the Commission, he was responsible for the preparation and adoption of six directives: renewable electricity, energy performance of buildings, biofuels, co-generation, eco-design of energy consuming products, and energy efficiency and services. Since he left in 2007, he enjoyed a career at lobby consultancy Hill & Knowlton as a Senior Adviser on transport, energy and environment; the lobby firm's current client list includes: Cathay Pacific City Airways, Électricité de France (EDF), and Ford. Werring was authorised to join the lobby firm so long as he “abstain from working on or giving advice on any affairs which you worked on yourself or which the service under your responsibility worked on.” Werring recently joined lobby firm cabinetDN in a similar role within the Energy, Transport and Environment team. He is also a staff member of the Clingendael International Energy Programme (CIEP) which contributes to the public debate on international political and economic developments in the energy sector and attracts the support of many big energy companies.

Luc Werring was at DG Transport and Energy for 23 years, latterly as Principal Adviser to the Director-General. While at the Commission, he was responsible for the preparation and adoption of six directives: renewable electricity, energy performance of buildings, biofuels, co-generation, eco-design of energy consuming products, and energy efficiency and services. Since he left in 2007, he enjoyed a career at lobby consultancy Hill & Knowlton as a Senior Adviser on transport, energy and environment; the lobby firm's current client list includes: Cathay Pacific City Airways, Électricité de France (EDF), and Ford. Werring was authorised to join the lobby firm so long as he “abstain from working on or giving advice on any affairs which you worked on yourself or which the service under your responsibility worked on.” Werring recently joined lobby firm cabinetDN in a similar role within the Energy, Transport and Environment team. He is also a staff member of the Clingendael International Energy Programme (CIEP) which contributes to the public debate on international political and economic developments in the energy sector and attracts the support of many big energy companies.

Werring's RevolvingDoorWatch profile is available here.

Mogens Peter Carl was Director-General at DG Environment and previously at DG Trade until he joined major lobby firm Kreab Gavin Anderson in 2010, in a move which was authorised by the Commission. He then moved to lobby consultancy Cabinet DN. In 2014 he moved again, this time to the law firm Gide as a senior adviser to work with its Brussels office on issues of European and international trade, EU competition and regulatory law.

Mogens Peter Carl was Director-General at DG Environment and previously at DG Trade until he joined major lobby firm Kreab Gavin Anderson in 2010, in a move which was authorised by the Commission. He then moved to lobby consultancy Cabinet DN. In 2014 he moved again, this time to the law firm Gide as a senior adviser to work with its Brussels office on issues of European and international trade, EU competition and regulatory law.

Carl's RevolvingDoorWatch profile is available here.