Uber: an EU lobby profile

The Uber Files, published by The Guardian, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, Le Monde, and other outlets lay out the lobby strategies, privileged access, revolving door hires, and indeed the capture of policy-making in various countries by the controversial hail-riding app.

Currently valued at over US$44 billion and an established member of the Big Tech lobby, Uber is a regular visitor to the European Commission’s Berlaymont building in Brussels. Its lobbying is geared to maintaining the privileges that gig economy businesses enjoy including exemptions from key social and labour responsibilities and from certain tax rules.

Read on for the low-down on Uber’s EU lobbying....

This article was updated on 14 July to reflect our urgent letter to Commission President Von der Leyen.

Protecting Uber’s business model

Uber has been an active EU lobbyist since at least 2013. Today one of its top priorities is the December 2021 EU proposal for new rules to better protect the rights of Uber drivers and other platform workers. Essential to Uber’s business model is its insistence that its workers are ‘independent contractors’. This allows Uber and platforms like it to effectively wash their hands of normal employer responsibilities to provide minimum wages and other benefits such as paid holiday, and sick leave. No wonder the record shows that Uber has had at least six high-level Commission meetings on this topic since April 2021, including three with the Commissioner responsible for jobs and social rights Nicolas Schmit.

In September 2019, Corporate Europe Observatory and AK Europa analysed the role Uber and other platform economy players – Airbnb, Deliveroo etc – played in influencing two previous EU files: the e-commerce directive and its services directive. On the latter, the platform economy lost when a coalition of municipalities, trade unions, and civil society groups successfully demanded that the Commission ditch a proposal that would have seen it grabbing veto power over local authority efforts to regulate Airbnb, Uber, and others.

Nonetheless, Uber is an influential lobby player at the EU level.

Über influential?

Considering its corporate value, it is perhaps surprising that Uber is not one of Brussels’ bigger lobby spenders, especially when compared to its significantly higher lobby spending in the US where it tops US$2 million annually.

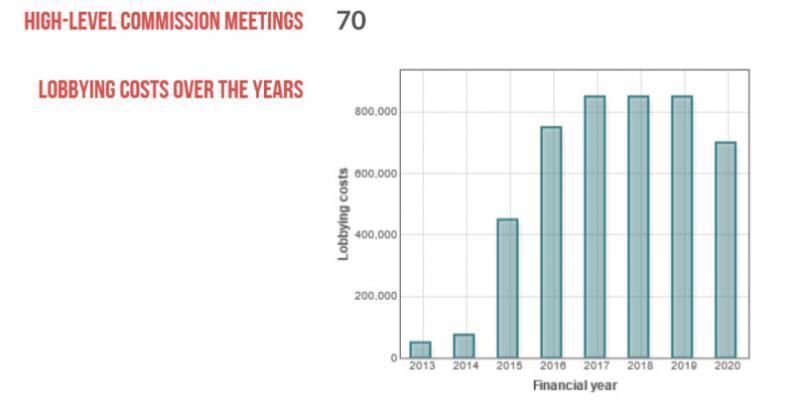

According to LobbyFacts, Uber’s self-declared EU lobby spending has grown 14-fold since it first joined the (voluntary) EU lobby transparency register in 2014, but from a low base of €50,000 to its most recent declaration of €700,000+ per year.

Yet Uber clearly has the ear of the Commission, with 70 high-level meetings, including 24 with Commissioners, since December 2014. So, how to explain this?

As we reported in 2019, Uber (and indeed Airbnb) have been able to mobilise the might of the Commission to their advantage, despite not having the numbers of lobbyists we might expect for big sectors such as finance or pharma. Uber only has three declared staffers working on lobbying (and together adding up to less than one full-time lobbyist). But who needs an army of paid lobbyists when you are already getting what you want: the Commission (and the EU Council) have tended to see these platforms as “bathed in the halo of ‘growth and innovation’” and have granted these platforms a safe haven.

The revolving door

The recent revelations about Uber’s lobbying operations have put various EU politicians in the spotlight, including Emmanuel Macron when he was French Economy Minister and Neelie Kroes, the Digital agenda Commissioner until 31 October 2014.

Kroes went through the revolving door to join Uber’s public policy board in May 2016, 18 months after she had left the Commission and at the end of rules which required her to seek authorisation for all new proposed roles and to not lobby her former colleagues. However, while commissioner, Kroes had offered fulsome support for Uber’s operations in the EU and it appears that there was significant contact between Kroes and Uber, including in the 18 months after she left office, alongside contacts with Dutch and EU decision-makers, raising serious questions as to whether all EU rules were followed.

Kroes has denied behaving inappropriately; read-up on Kroes’ contacts with Uber, her business background, and her involvement in other scandals here.

Hired lobby guns

Finally, when it comes to its lobby tactics, Uber is at the centre of a network of allies able to amplify its messaging and demands. In effect Uber’s approach to lobbying appears to mimic its business model, with the emphasis on outsourcing. Take for example the network of intermediary lobby consultancy firms and even law firms contracted by Uber and paid to advise on lobby strategies.

Since 2017 it has employed Acumen Public Affairs, paying them between €100,000-199,999 in the 2020 financial year. LobbyFacts (which holds EU lobby data back to 2012) reports that in the past Uber has used six other lobby firms (Aspect, Delany & Co, EuroNavigator Ltd, FIPRA International Limited, Policy Action Ltd, and Technology Policy Advocates). Uber has also previously contracted the law firms Covington & Burling LLP and Gide Loyrette Nouel for added lobby firepower, with spending on such firms totalling more than €1 million since 2013.

Amplifying its voice

Alongside Uber’s lobby and law firms, it is also well-connected to some familiar corporate-friendly lobby actors.

Take BusinessEurope, one of Brussels’ most active lobby groups, and its Corporate Advisory and Support Group (ASG), of which Uber is a member, alongside Apple, Facebook, Google, Big Tobacco, fossil fuels, and others. The ASG is influential in setting BusinessEurope policy and priorities and, as expected, BusinessEurope is an ally to gig economy platforms. ASG members can also participate in an annual day-long meeting with several different EU commissioners.

Uber is also a member of the Computer and Communications Industry Association (CCIA) which brings together Google, Facebook, Amazon, and other Big Tech players to lobby in both Washington DC and Brussels. And then there is Uber’s membership of other trade associations such as SME Connect (although it is hard to argue that this global business worth billions qualifies as an SME); the International Association of Public Transport (an employers’ association, even though Uber refutes being an employer itself and is arguably not a public transport provider either) and AVERE, the electric vehicle lobby group.

Uber is a member of several new lobby outfits, apparently lobbying on the platform workers proposal. Move EU (the European Association of On-Demand Mobility) represents “the leading actors in the field of new #mobility services”, and almost all of its 11 meetings with the high-level of the Commission have been on ‘platform workers’. Another lobby group, Delivery Platform Europe only joined the EU lobby register in September 2021 but is also active on the Commission’s proposal. Its other members include Deliveroo and Bolt.

Finally, Uber is a member of various think tanks, a well-known lobby tactic for corporate interests keen to influence EU policy debates. In 2020 the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) produced a report on the collaborative economy funded by Uber, Airbnb, and others. The Centre for Regulation in Europe (CERRE) brings together numerous Big Tech lobbies and others including Uber, while the think tank Ambrosetti Club works “at the side” of companies and runs a management consultancy arm.

Conclusion

Uber’s EU lobby footprint is not straightforward. It declares relatively low lobby spending for a company of its financial value, but clearly has excellent access to top decision-makers in the Commission. Likely this access comes from goodwill towards the gig economy within the Commission, while Uber’s network of lobby firms, trade associations, and think tanks helps promote its reputation and lobby demands within the Brussels bubble. And Uber’s breathtakingly brazen liaison with Neelie Kroes is a shocking example of how corporate interests use the revolving door.

Uber’s lobbying reveals its preference for privatising profit and socialising risks including responsibility for its workers’ employment rights. MEPs and member states scrutinising the current platform workers proposal must use this opportunity to rein in Uber’s business model.

Read our comment piece on this topic for The Guardian here.

Stop press!

Today, 14 July 2022, Corporate Europe Observatory and the Alliance for Lobbying Transparency and Ethics Regulation have written an urgent letter to President Von der Leyen to demand urgent action following the Uber Files leaks. Among our demands are:

- A full and detailed investigation into Kroes’ activities in the light of the then Code of Conduct and her wider Treaty obligations to behave with “integrity and discretion”.

- Immediate and permanent removal of the Commission access pass of Kroes.

- The application of financial penalties upon Kroes for any and all breaches of the Code and Treaty.

- A full review of Commissioner revolving doors rules.

- A full investigation into freedom of information failings.

- The suspension of Uber from the EU lobby transparency register.

The letter is available here.

Stop press again!

The European Commission has now, belatedly, replied to our urgent letter. The reply is dated 16 November 2022, and can be read here.

The letter confirms that OLAF, the EU's anti-fraud office is now investigating the allegations regarding the #UberFiles and ex-Commissioner Kroes. But the Commission refuses other actions until Olaf's investigation is completed, and also rejects any accusations of wrong-doing on its own part. Corporate Europe Observatory is considering several options for follow up, so watch this space!