Big Tech brings out the big guns in fight for future of EU tech regulation

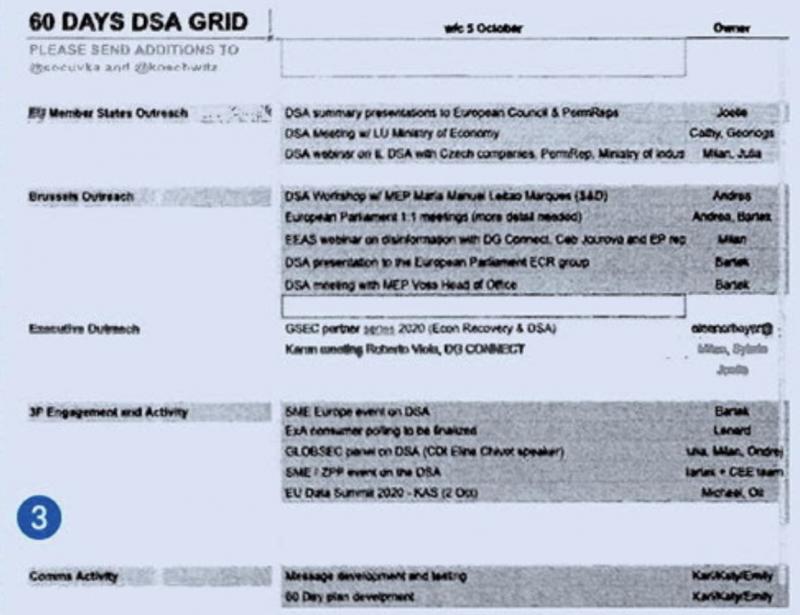

The next big EU lobby battle is already underway: Google, Facebook, and Microsoft are among the companies making huge efforts to shape the upcoming Commission proposals to regulate the digital market. In spite of a new lockdown, the Brussels Bubble is back in action at full speed, with a flurry of online lobby meetings and debates plus highly questionable research papers. Most unexpected of all, a leaked Google strategy document exposed the company’s aggressive pushback against ideas that could affect the company’s market power.

The Commission is due to present its proposals tomorrow (15 December) but these are just the first chapters in what looks like a lengthy lobby battle. The ideas being considered have the potential to start tackling the excessive market power of Big Tech, empowering smaller businesses and enabling people’s control of their online lives. Given the potential implications for Big Tech's profits and business models, it was inevitable that massive lobbying would follow. We shouldn’t be complacent: this corporate campaign threatens to shape the policy discussions.

What is at stake?

The Digital Services Act (DSA) is set to update the legal framework for online activities, the e-Commerce Directive. The Act will likely cover different areas, including the management of illegal or harmful content and the vetting of commercial users. It could also clarify the legal background for the “collaborative economy”, services like AirBnB and Uber to improve the enforcement of rules and to increase data access for regulators.

This Act could also start addressing surveillance-based advertising. This follows growing concerns, especially following the Cambridge Analytica revelations, regarding business models based on the extensive and intrusive collection of users’ personal data to feed personalised adverts to them. There are growing concerns among academics, civil society, and politicians that these business models clash with citizens’ rights to privacy, and that they enable manipulation and disinformation campaigns. In a plenary vote in October, the European Parliament laid out its position on the matter: targeted advertising should “be regulated more strictly in favour of less intrusive, contextualised forms of advertising” and MEPs called on the Commission to start assessing options for regulating it, ultimately leading to a ban. At the moment, the Commission is unlikely to support a ban but these could be the first steps towards it.

The ideas being considered have the potential to start tackling the excessive market power of Big Tech, empowering smaller businesses and enabling people’s control of their online lives. Given the potential implications for Big Tech's profits and business models, it was inevitable that massive lobbying would follow.

Then there is the competition component of the package: the Digital Markets Act (DMA). This is perhaps even more interesting as it could finally address the excessive market power of Big Tech firms. This would include the introduction of the concept of digital gatekeepers, broadly meaning market dominant companies (although exactly how the concept would be defined is unclear so far), and adopt a set of rules applying only to these gatekeepers. Leaked Commission plans showed that EU officials were considering banning gatekeepers from self-preferencing their own products (ie. giving their own products top billing in internet searches); banning the bundling of products , thus requiring users to sign up for more than one service; and demanding mandatory auditing of gatekeepers’ advertising services, including their profiling of users.

The competition proposals would also include a new ‘markets investigation’ tool to improve the functioning of competition inquiries. This would mean that instead of only being able to investigate the behaviour of one company at a time, authorities would be able to investigate a whole market in order to assess whether there are structural characteristics that prevent competition and harm consumers. This could be a great step forward for the EU’s competition policy which has so far been marked by investigations that take over a decade and where the possible remedies are often limited to monetary fines that make good headlines but have real no impact on the immense profits of Big Tech firms. After apparently receiving negative assessment from the Regulatory Scrutiny Board, this tool will likely be downgraded in the Commission’s final proposal.

One big disagreement at the political level of the Commission seems to relate to the remedies available to authorities when they find market abuses and especially the possibility to demand structural separation of different parts of these companies, commonly referred to as ‘forced break ups’. Commissioner Breton is one of its proponents, but Vice-President Vestager seems to believe it would be “too far-reaching”.

Rumours about what to expect from these new policies change every day, and it seems that the Commission will be working up until the last minute to finalise the details. Tomorrow’s presentation of the proposals by the Commission is also just a first step: the European Parliament and Council will then discuss and amend them before the three institutions come together to find a common position via the trilogue process. It is highly likely that these discussions will be long and arduous. What is clear so far is that corporate lobbying to influence them has already started.

Who has been lobbying?

The quick and simple answer is Big Tech firms, with Google leading the pack.

This is clear from the lobby meetings proactively disclosed by the upper echelons of the Commission (commissioners, their cabinets, and directors-general). Since the start of the Von der Leyen Commission, 158 meetings were logged as including discussions on the DMA or DSA Sidenote Source: Integritywatch.eu, Data checked 08/12/2020, Meetings filtered by issues: Competition, Digital Competition, Digital Services Act, DSA, Digital Markets Act, DMA, Digital Package, Digital Policy, Digital Agenda, Gatekeepers, Platforms, Digital Economy. For meetings logged only with the subject ‘competition’, CEO filtered out lobbyists whose business is not likely to be affected by the DMA (ie. companies not active in the digital market or when referencing other economic areas). .

These meetings involved 103 organisations, mostly companies and lobby groups. Only 13 actors had at least 3 or more meetings logged on these issues. Google stands out with the most meetings with Microsoft and Facebook trailing close behind. Apple and Amazon have also lobbied on the DMA and/ or DSA, although they rank lower overall with two and one meeting respectively.

| Lobbyist | Meetings |

| 5 | |

| American Chamber of Commerce to the European Union (AmCham EU) | 4 |

| Bureau Européen des Unions de Consommateurs (BEUC) | 4 |

| eu travel tech | 4 |

| European Magazine Media Association (EMMA) | 4 |

| European Newspaper Publishers' Association (ENPA) | 4 |

| Snap, Inc. | 4 |

| Spotify Belgium SA | 4 |

| DIGITALEUROPE (DE) | 3 |

| Facebook Ireland Limited (FB-I) | 3 |

| Microsoft Corporation | 3 |

| Prosus | 3 |

| Schibsted ASA | 3 |

Two lobby groups rank high: DigitalEurope and the American Chamber of Commerce to the European Union - Big Tech firms are members of both.

Other business interests have also been active: eu travel tech, the lobby group representing companies like Booking.com; Snap.Inc, the company owning Snapchat; the European music streaming service, Spotify; the technology investor Prosus; the European newspaper publishers' association (ENPA) and the European Magazine Media Association (EMMA); and the media and marketplace group, Schibsted ASA.

Google stands out with the most meetings with Microsoft and Facebook trailing close behind.

Only one NGO – the umbrella organisation of european consumer associations, BEUC - features on the list of top lobbyists on the DMA / DSA, with all other spots being taken by corporate interests. Other NGOs have been active too although with less access: Reporters Sans Frontiers, the European Digital Rights network (EDRi), and the Electronic Frontier Foundation, all had two lobby meetings.

This list gives us a glimpse of who has been active in this lobby battle so far, though it is far from complete. To start with, it doesn’t cover meetings with the Commission officials who are actually writing the proposals. Only the highest levels of the Commission (about 10 per cent of the whole staff) proactively publish their lobby meetings. On top of that, those that should publish their meetings often do so very late: Vice-President Vestager, for instance, hasn’t logged a single meeting since mid-October Sidenote Checked 08 December 2020 .

And these meetings don’t include the last minute lobbying frenzy apparently underway, directed at the highest echelons of the Commission. Google’s CEO, Sundar Pichai, for instance, has been in touch with at least two commissioners in the past weeks, Breton and Jourová. This is not to mention the meeting that took place on 2 December between Commissioner Breton and representatives of Google and Youtube (both belonging to Alphabet), Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and TikTok, alongside European companies like Booking.com (full list here). It seems that the Big Tech firms might have luck on their side as they didn’t even have to ask for this meeting: it was Breton himself who took the initiative to invite them to discuss the draft proposals with him.

Corporate Europe Observatory and ALTER-EU have criticised the red carpet treatment being given to a few extremely well-resourced and powerful companies that are more than able to lobby for themselves. Following our letter, Commissioner Breton reached out to not-for-profit organisations, including BEUC and EDRi, to set up a meeting.

Beyond the Commission: laying the groundwork in the Council and Parliament

This lobby battle will not finish once the Commission’s proposals are presented. At that point, it will be up to the European Parliament and Council to start discussing them and to make their own amendments.

In fact, the Parliament has already been discussing the DSA for the past year, and has produced four separate reports on what it expects to see within the Commission’s proposal. As a consequence, we can already see how it has been lobbied: 333 meetings were logged by MEPs relating to these proposals Sidenote Meetings filtered by the tag Digital Services Act, DSA, New Competition Tool - no meetings were found which were tagged as Digital Markets Act or Digital Competition. Data taken from Parltrack .

Interestingly, the top 10 lobbyists of MEPs look different from those meeting with the Commission but Google still leads in meetings with MEPs (14).

| Lobbyist (s) | Meetings |

| 14 | |

| Center for Democracy & Technology (CDT) | 7 |

| European Digital Rights (EDRi) | 7 |

| Mozilla Corporation | 7 |

| Vodafone Group | 7 |

| Bureau Européen des Unions de Consommateurs (BEUC) | 6 |

| 5 | |

| Snap. Inc | 5 |

| The European Telecommunications Network Operators' Association (ETNO) | 5 |

| Access Now Europe | 4 |

| AirBnB | 4 |

| Allied 4 startups | 4 |

| Apple Inc. | 4 |

| LVMH | 4 |

Once again though, these numbers don’t tell the whole story – as Transparency International EU found, by September 2020, only 44 per cent of MEPs had published their lobby meetings, so likely lobbying has been much higher.

We can expect even less transparency from the Council, where there is no central obligation to disclose lobby meetings - less than half of permanent representations to the EU do so voluntarily. And even then disclosure tends to be restricted to the higher levels, normally the Ambassador and Deputy Ambassador, leaving all the policy officers outside of the scope of disclosure.

An example of how this plays out can be seen with the Portuguese Permanent Representation, which is due to take over the Presidency of the Council in January 2021 and has recently started disclosing lobby meetings of its Ambassador and Deputy. The official log lists only nine meetings with a variety of actors (including Facebook’s new head EU lobbyist and DigitalEurope). However, at a recent event hosted by the US tech lobby group, the Computer and Communications Industry Association (CCIA), a representative of the Portuguese Permanent Representation said that the Portuguese had held dozens of meetings with stakeholders to discuss the DSA and DMA. One of those lobbyists seems to have been the CCIA itself, which has apparently had not one, but a “series of meetings” with “Portuguese politicians and senior officials”. None of these were listed in the official Portuguese lobby meetings log.

Google’s leaked lobby strategy: creating conflict and mobilising third parties

An interesting piece of the lobbying puzzle came to light last month, when the newspaper Le Point published information on a leaked copy of Google’s lobbying strategy. The document laid out in black and white the strategy the company is deploying to fight regulation that could hurt its profits margin. The main components were to:

-

Lobby at Parliament, Commission and member state level;

-

Re-frame the political narrative around costs to the economy and consumers;

-

Mobilise third parties (such as think-tanks and academics) to echo Google’s message;

-

Mobilise the US Government;

-

Create “pushback” against Commissioner Breton (who was seen as supporting potential break ups)

-

Create conflict between Commission departments

The leaked strategy created some drama and as a result Google’s CEO, Sundar Pichai, was forced to apologise to Commissioner Breton in a meeting. However, beyond some schadenfreude the apology changed nothing: Google seems to have done exactly what it set out to do in the strategy.

On the same day of the leak, Reuters reported that the think-tank the European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE) was to publish a study that estimated the economic cost of the (as yet unknown and unpublished) proposals at about 85 billion euros to the European economy. If you find yourself wondering how an external organisation can estimate the economic impact of a regulation whose provisions have not yet been announced or finalised, you’re not alone. Tommaso Valetti, the former Chief Competition Economist of the Commission analysed the report and called it ”ridiculous”. Unsurprisingly, the study was financed by Google.

A few weeks later the Wilfried Martens Centre (the EPP linked think-tank) hosted a debate on whether the DMA was “giving the European Economy and Consumers what they need right now”. Strangely, despite the title, the debate didn’t feature a representative from a consumer organisation. Instead it gave a forum to the author of ECIPE’s report and a representative of the Center for Data Innovation, another think-tank funded by Google. The event was described as “powered by Google”, not surprising given that Google is also a member of the Wilfried Martens Centre itself.

It doesn’t stop there: the tech lobby group Computer & Communications Industry Association published a study it had commissioned arguing digital services were a positive contributor to everything from SMEs to competition and consumer choice. Tech firms were deeply involved in the making of the report apparently providing insights and participating in consultation rounds with the consultancy firm writing it The report was then launched with an event with MEPs and member-state representatives.

The Center for Data Innovation hosted its own debate in December to discuss “How the Digital Markets Act Could Reshape the EU’s Digital Economy”. Who was on the panel? Two policy-makers and lobbyists from Google and Microsoft.

We should expect that Google will not be the only company implementing these aggressive lobbying strategies.

We should expect that Google will not be the only company implementing these aggressive lobbying strategies. The Big 5 (Google, Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Microsoft) are all very well-networked. After Corporate Europe Observatory and LobbyControl submitted a series of alerts and complaints to the EU lobby register, the five firms updated their lobby declarations and expanded the number of lobby groups and think-tanks that they declare funding or to which they are affiliated. Now, the Big 5 firms declare being members or funding 73 different organisations between them. Yet, as LobbyControl pointed out, this is still not complete.

This network goes a long way towards explaining how Big Tech is able to control the narrative surrounding EU policy-making on digital issues. After all, as Google discusses in its lobbying leak, third parties can echo a company's message.

Big Tech = Big Lobbying

While the lobby meetings and leaked strategy certainly don’t tell the full story, they nevertheless allow us to say with certainty that Big Tech firms are actively opposing any real threats to their business models and profits. This should be a concern to all, because these are also some of the companies with the biggest lobbying budgets in the EU. While the political environment points to a general willingness to finally regulate these companies in a way that protects consumers, freedom of speech, privacy and competition, there is a real danger that the upcoming discussions could instead be shaped by Big Tech firms.

It is crucial to remember that these Acts won’t merely affect these firms. Depending on the level of ambition, the final regulation could also give a better chance to small and medium sized companies in the EU compete and negotiate with Big Tech, and protect consumers from manipulative and exploitative practices. They could also, perhaps, start tackling the surveillance-based advertising system and how it's negative impacts on citizens’ rights and the quality of democracy.

The revenue implications for Big Tech could be significant, which is why it will lobby hard to undermine any progress. Thus it is all the more important for policy-makers to: be cautious when dealing with corporate lobbyists and corporate-funded organisations; seek out independent input; and reach out to citizens.

We have learnt from previous tech policy battles over the ePrivacy and Copyright directives, that these can become incredibly technical or get co-opted by lobbyists and, at times, become part of very toxic public debates. It will be up to citizens, journalists, and civil society groups to counter this to ensure that whatever regulation we end up with will put consumers and democracy at its core.