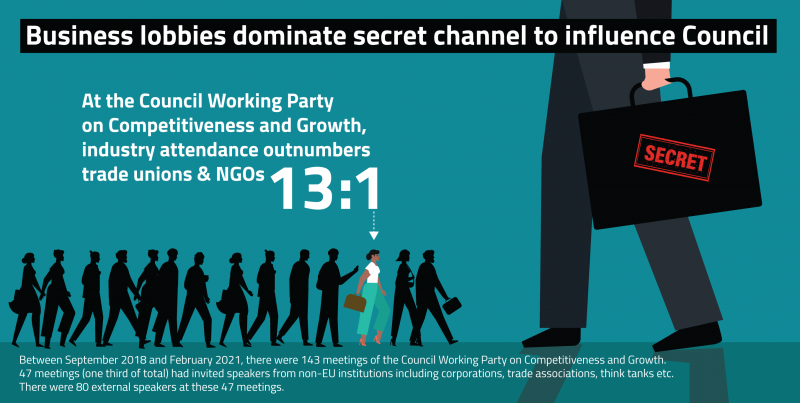

Business lobbies dominate secret channel to influence Council

You may not have heard of the EU Council’s 150 working parties, but they play an important role in preparing the positions that member states take in the Council on proposed EU laws and policies. New research by Corporate Europe Observatory shows how a key working party on competitiveness and growth offers privileged access to corporate interests to present and discuss their demands. Business interests outnumber trade unions and NGOs 13 to 1 in terms of attendance at these meetings, while dissenting voices to the prevailing EU orthodoxy of ‘competitiveness’, ‘completing the single market’, ‘innovation’, and ‘better regulation’, are not invited.

Behind closed doors, with little or no transparency about what is said and who is saying it, this secret lobby channel is surely prized by industry. This practice has continued over a number of years, likely extending long before the 30 months analysed in this study. It is facilitated by member state governments holding the Council presidency who issue the invitations, and overall must be seen in the context of a Council which is far too eager to do the bidding of big business. Meanwhile the Council Secretariat seems unable to intervene: a commitment in July 2019 to put in place guidelines on this issue has not been met. (21 October 2021: please see update below.)

Council working parties – what you need to know

There are 150+ working parties and other preparatory bodies in the EU Council which develop positions on policy and proposed legislation for member state ministers to agree. Officials from the 27 member states attend working party meetings, sometimes on a weekly basis. The member state which holds the rotating presidency of the Council (currently Slovenia, previously Portugal and Germany) is responsible for setting the agenda of working party meetings and chairing them. It is therefore their decision whether or not to invite external speakers.

The focus of this analysis is the Working Party on Competitiveness and Growth which meets via sub-groups on Better Regulation, Industry, Internal Market, and Tourism. It prepares draft positions and decisions for the Competitiveness Council of member state ministers and its current work programme includes hot topics such as the EU’s digital strategy, industrial policy, and various aspects of the single market. Upcoming issues will include controversial plans to provide a new form of investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), essentially legal privileges for corporations investing within the EU.

The activities and operations of Council working parties are under-scrutinised considering the key role they play in the development of Council positions on draft legislation and in setting the EU’s agenda. This reflects the secretive way in which they are allowed to operate: legislative documents are not routinely published, and there is no requirement to minute either the discussions or the positions articulated by member states. This opacity has been heavily criticised by the European Ombudsman, MEPs, and InvestigateEurope, while Corporate Europe Observatory has illustrated how these working parties are key targets for corporate lobbyists. On too many issues, member state ministers and officials act as ‘middle men’ for corporate interests. And as set out below, the opportunity to address a Council working party meeting surely represents a boost to corporate lobby firepower.

Brussels’ biggest corporate lobbies dominate

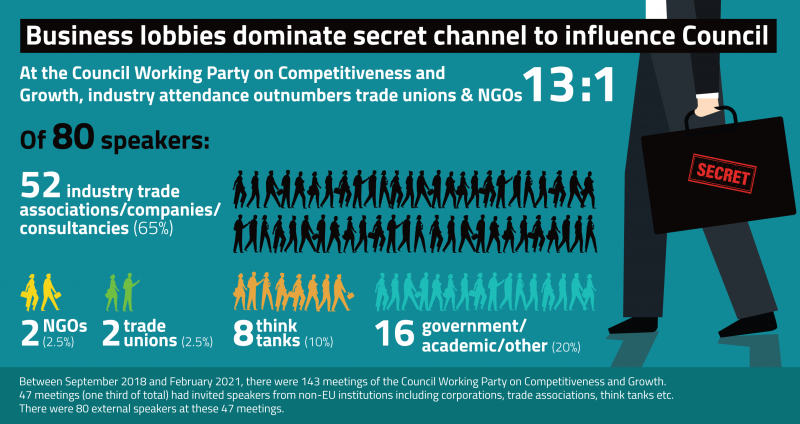

Industry lobby groups have far greater access to the Council’s Working Party on Competitiveness and Growth than any other type of external organisation, as this spreadsheet makes clear. With 52 out of a total of 80 external speakers Sidenote External is defined as an organisation which is not part of the EU architecture coming from a company, trade association, or consultancy, and only 4 from NGOs and trade unions, industry attendance outnumbered public interest groups 13:1 during the 30 months analysed.

BusinessEurope. DigitalEurope. European Chemical Industry Council (CEFIC). European Round Table for Industry. Microsoft. Sanofi. These are just some of the corporate interests which have enjoyed privileged access to Council policy-makers in the period studied, making presentations and participating in discussions at the working party. They are some of Brussels’ highest spending lobby groups, with just these 6 groups racking up a combined declared EU lobby spend of over €21 million per year.

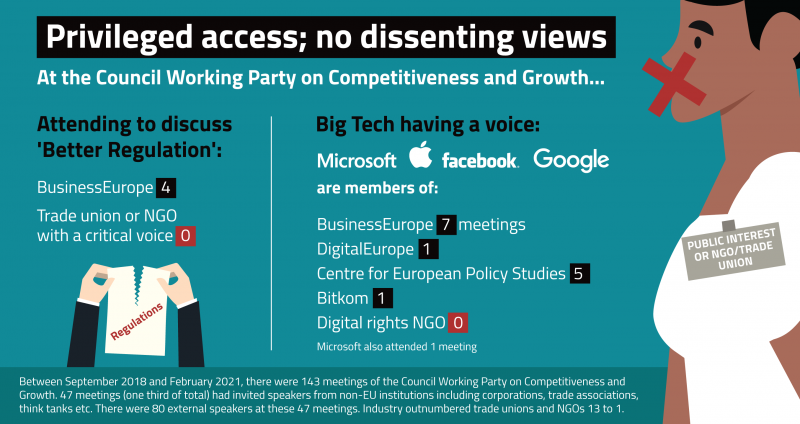

BusinessEurope alone has attended the working party at least seven times in the period studied, discussing deregulation, artificial intelligence, and the single market. While it is a social partner at the EU level (which is sometimes used to justify some of its access to EU decision-makers) its trade union social partner counterpart, the European Trade Union Confederation, has attended only one meeting of the working party in the 30 months analysed.

The interests of Big Tech seem well represented at the working party’s meetings. As well as Microsoft’s own appearance, Microsoft, Apple, Facebook, and Google are members of BusinessEurope (which has had seven meetings), DigitalEurope (one meeting), and think tank the Centre for European Policy Studies (five meetings). The European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE) also attended one meeting and has close links to the tech lobby. This is especially relevant considering that this working group is responsible for the Council’s scrutiny of the EU’s digital strategy and its accompanying legislation. In the six months since mid-December 2020, the proposed Digital Markets Act and / or Digital Services Act have been discussed 25 times in the working party’s Internal Market sub-group (spreadsheet).

The small and medium-sized (SME) business sector is not entirely excluded, although attendance by the sector’s trade association SMEUnited totals 3 meetings, which amounts to only 4 per cent of all external speakers.

This working party also does not seem to be too fussy about the green credentials of its guest speakers. Eurofer (steel manufacturers), Eurometaux (metal producers), CEFIC (chemicals industry), CEMBUREAU (cement industry), and Nederlandse Gasunie (the fossil gas company) are all found on the list of speakers.

Getting to grips with EU jargon

‘Better Regulation’: a rebranding of the EU’s deregulation agenda, used by business to argue for the weakening of rules protecting consumers and the environment, or the obstruction of new rules. Better Regulation has changed how EU rules get made and given business a bigger say in the process. Read more.

‘Digital Strategy’: the EU’s strategy to set a regulatory framework for digital service providers. The strategy and its proposed legislation – the Digital Markets Act and the Digital Services Act – are heavily lobbied, including by Big Tech. Read more.

‘Industrial Strategy’: a new initiative to bring business into climate and digital policies by member states and EU institutions. These alliances with industry will enable them to self-regulate, advocate for public funds, and / or push for false solutions to the climate crisis. Read more.

‘Innovation’: sounds very good, but is often co-opted by business interests as a cover to demand public funds or a relaxation of the rules. The so-called “innovation principle” is an industry invention which aims to counter both the precautionary principle and the polluter-pays principle. Read more.

‘One in, One out’: a principle which aims to ensure that any new regulatory so-called ‘burdens’ are offset by removing equivalent ‘burdens’ in the same policy area. This approach threatens to push back against new regulations at a time when tackling the climate crisis and COVID-19 pandemic require tougher rules. Read more.

‘Single Market’: the centre-piece of the EU project which aims to reduce barriers to selling goods and services within the EU. However, there are serious concerns that the focus on ‘competitiveness’ and ‘removing barriers’ favours big businesses, which operate at economies of scale. There is also a risk that the market will be prioritised over social and environmental concerns and that it will be used as a tool for deregulation and pre-empting progressive regulations. Read more.

This is what privileged access looks like

How convenient for active lobbyists to receive invitations to address these Council working party meetings as they provide a unique way to get to know member state officials. As the Council does not keep let alone publish lists of officials attending such working parties, this personal contact could help put invited lobbyists on the inside track and is likely to be treasured by a diligent lobbyist.

Additionally, these meetings provide an opportunity to present an organisation and its demands. The speakers talk to a precise topic and their presentations are usually circulated to the working party members soon afterwards, reinforcing the privileged access that the lobbyists have already been granted. And the topics of these presentations are not chosen randomly. Corporate lobbies’ inputs are sometimes followed by a Council discussion on the same topic which effectively provides the lobby groups with the perfect opportunity to influence the subsequent discussion.

Having an impact

On 8 March 2019, BusinessEurope, DigitalEurope, and EuroCommerce (the retail industry lobby) were all invited to individually address the working party on their priorities for the EU single market. This was followed by a discussion at the same meeting to prepare Council Conclusions on ‘An updated approach for the Single Market’, finally published in May 2019. Even if the lobbyists were not present for that latter discussion (the Council has told us that speakers are not present for working party deliberations), surely the officials had their lobby demands still ringing in their ears.

This meeting took place just when the debate on the proposed, and highly controversial, Services Notification Directive was coming to a head. By March 2019 it had become clear that the directive no longer enjoyed the support of a significant number of member state governments. The European Commission was therefore looking for alternative ways to introduce oversight and enforcement powers over decisions taken by national authorities and city councils on a vast range of services, from childcare to energy and water. At the 8 March 2019 meeting, BusinessEurope demanded the following:

“Inventory of notification requirements for Member States under the EU Single Market acquis and their actual impact on regulatory environment in the Single Market should be carried out and access to such notifications made by Member States through one information access point, such as Single Digital Gateway, ensured. Duty to explain and justify the notified measures should be reinforced and effectiveness of notification obligations on Member States should be revisited together with stakeholders regularly.”

“Access to such notifications made by Member States through one information access point” was introduced later that year, pleasing big business, but threatening to undermine the policy space of local authorities to provide services to local people in the way that they choose.

Dissenting views are not invited

As the spreadsheet shows, NGOs and trade unions together receive only a thirteenth of the access provided to business interests to address this working party. This is despite the fact that the working party covers numerous issues of interest to green groups, consumer organisations, trade unions, and others. These include ‘better regulation’, digital strategy, chemicals regulation, forestry, raw materials, industrial strategy, etc.

As mentioned above, some think tanks attending are known for being close to corporate interests. It’s clear that officials attending the working party aren’t being exposed to countervailing views.

A case in point is the EU’s controversial deregulatory drive ‘Better Regulation’, the topic of one of the working party’s sub-groups which held 18 meetings in the period studied. Of these, 19 guest speakers participated in 10 meetings; BusinessEurope, an ardent supporter of deregulation at the EU level, was a regular visitor, presenting at 4 meetings. It has reported in its newsletter that one of its presentations on Better Regulation “was well-received by many members of the Working Party and stimulated a constructive exchange of views”. Apparently, BusinessEurope was able to make various points including to make the case for “regulatory simplification” - a highly controversial, pro-deregulation position.

Meanwhile the think tank CEPS spoke to the group 3 times, including to present its study, commissioned by the German Government, which looked at how to implement the controversial 'One in, One out' approach, a key element of the European Commission’s ‘Better Regulation’ agenda. The CEPS study has been critiqued by the trade union movement. The Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), an organisation of rich country governments, also attended 4 times. The only NGO to address the group, the Open Government Partnership (which includes many governments on its steering committee so is not a traditional NGO), did not challenge the ‘Better Regulation’ orthodoxy, presenting instead on the need for transparency, participation, and accountability.

‘Better Regulation’ is not simply a technical regulatory process; it represents a pro-corporate political agenda. Yet the working party only hears from supporters of ‘Better Regulation’. It is not listening to trade unions and NGOs who have a critical voice on ‘Better Regulation’ and its threats to the environment, human health, workers' rights, and consumer rights.

Secret discussions, behind closed doors

As shown above, it can be easier to find out when corporate lobby groups address these working party meetings from boasts in their own newsletters, rather than from any official Council source!

Too often published working party agendas say that a “stakeholder” will attend without providing any other information, although this practice has improved since we reported this to the Council in 2019.

Additionally, our spreadsheet shows three meetings where the agenda indicated that external presentations were made, but the Council had no information as to who those participants were. For example, the agenda for a May 2019 working party meeting in Romania (which held the Council Presidency at the time) shows that the “automotive industry” and “the EU chemicals industry” made presentations. However the Council Secretariat has told us that “we have not found any other documents related to this meeting” including which lobbies were involved. This indicates a worrying lack of transparency and proper record-keeping.

Furthermore, the presentations made by lobbyists are not proactively published on the Council meeting’s website page and instead have to be obtained via access to documents requests (see this as one example). These are handled in a cooperative manner by Council officials, but the documents are not always made available when requested and the Council website remains a deeply ineffective transparency tool which is cumbersome and confusing to use. Bizarrely, most meetings of the Better regulation sub-group are labelled as meetings for “Competit.Growth – Shipbuilding”, even though such a group does not exist and shipbuilding is not a topic on the agenda! Importantly this means that the meetings are less easy to track.

Shockingly, there is no requirement to minute working party meetings, meaning that the discussions remain essentially behind closed doors, with this lobby channel below the radar of public and media scrutiny.

Finally, some invitees are not part of the EU lobby transparency register. This includes Industry4Europe, the trade association for trade associations, which has 156 industry members and is “dedicated to campaigning for an ambitious EU industrial strategy”. It has attended this working party twice.

At the pleasure of the presidency

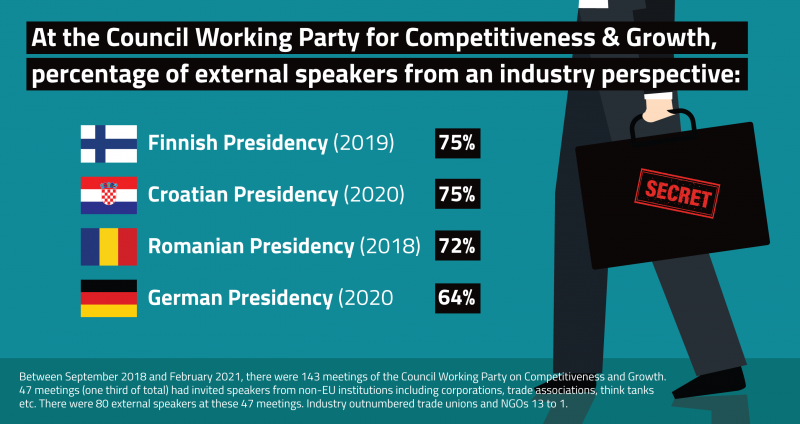

The member state holding the rotating presidency of the Council (currently Slovenia) sets the agenda for working party meetings, which gives it huge discretion to invite external speakers. According to our spreadsheet, for the Finnish and Croatian Presidencies, 75 per cent of their external speakers were from a business perspective. For the Romanian and German Presidencies, the figures were 72 per cent and 64 per cent respectively.

Many presidencies use this as an opportunity to favour domestic companies. In the period analysed, the Presidencies of Austria (AVL List GmbH), Finland (DIMECC and Metsä Group), Germany (Festo and Fraunhofer Institute for Material Flow and Logistics), and Portugal (Indico Capital Partners) all invited national companies to address the working party. The German Government also invited a domestic trade union to address a meeting too – only one other trade union body attended during the whole of the 30 month period studied.

Is this pure coincidence or favouritism towards domestic business interests? It should certainly be seen in the wider context of how EU Presidencies are used as vehicles to promote domestic corporate interests, from sponsorship deals, to one-off policy initiatives, and public events.

But it is not just these working party meetings where industry secures privileged access. The governments holding the rotating EU presidencies often organise informal sessions with corporate lobbies too. The European Services Forum (industry’s lobby group on services) has had regular informal meetings (see this and this) with the Trade Policy Committee, an important Council preparatory body. These events are hosted by the presidency of the Council and have enabled Vodafone, HSBC, and Deutsche Telekom among others to have cosy chats and even cocktails with officials from member states and the European Commission.

Meanwhile, in the margins of Coreper meetings (the Council grouping which brings together the ambassadors of the member states), presidencies sometimes organise informal lunches or breakfasts, allowing the likes of DigitalEurope and Allied for Startups (whose corporate board includes Google, Apple, and Facebook) to hobnob with top member state officials.

Since 2012, a group of Council member states calling themselves 'Friends of Industry' have met once a year to “discuss recent developments related to industrial policy at EU level”. In October 2019, the Friends of Industry met with the Federation of Austrian Industry, Austrian Federal Economic Chamber, SME United, and the Union des Industries Ferroviaires Européennes (rail industry) in a meeting convened by the Austrian Government in Vienna. The resulting declaration adopts a range of industry demands including on trade, climate policy, and digitalisation.

Time for action

In July 2019 Corporate Europe Observatory wrote a complaint to the Council about the way in which corporate lobbies are offered privileged access to the Working Party on Competitiveness and Growth. The Secretary-General’s swift response said he would “review the practice so far and issue guidelines for the [Council] services and the Presidency on the attendance of external guests at the meetings of the Council and its preparatory bodies”.

However, two years on, the guidelines have not materialised – and the privileged access by corporate lobbies continues. The Council Secretariat has not responded to our recent request to provide an update on this matter. (21 October 2021: please see update below.)

The Council should follow through on its commitment to produce guidelines on this topic. There should be far more transparency about the work of Council working parties, including the publication of minutes of all meetings held.

But these guidelines will not be sufficient. Further action to tackle the problem of privileged access and corporate bias will be required. Those with private and commercial interests should not be favoured with invitations to present their policy demands to member state officials tasked with developing Council positions on key topics.

It’s time to block this secret channel for corporate lobbyists, and for the EU institutions and member states to challenge the EU mantra to ‘complete the single market’ and defend industry.

Update: 21 October 2021

Since we published this article, the Council Secretariat has issued guidelines on the “occasional attendance of third parties, including interest representatives, at meetings of the Council or its preparatory bodies".

On the plus side, the guidelines require that:

-

the attendance of specific lobbyists should be authorised before it goes ahead

-

any invited lobbyists are listed on the public agenda

-

only registered lobbyists are invited and that their lobby registration number is listed on the public agenda

-

any presentations or documents circulated by lobbyists are made public

Interestingly the guidelines also say “where several (sometimes competing or opposing) interests are involved, particular attention should be paid to ensuring a balance of representation so as to avoid bias in the information shared with the Council.”

That implies that if big business is invited to address a working party, that maybe an SME, trade union, or NGO should also be invited. Our research, detailed above, shows that this has not been the case up to now, and that industry attendance has massively outnumbered attendance by other interests.

But we consider that the Council should go much further than this. Those with private and commercial interests should not be favoured with invitations to present their policy demands to member state officials tasked with developing Council positions on key topics. The revised EU lobby transparency register, launched in September 2021, now differentiates between those who advocate for commercial interests and those who promote the public interest. This differentiation should now be used to ensure that only those with a public interest remit can be invited to attend occasional Council meetings.