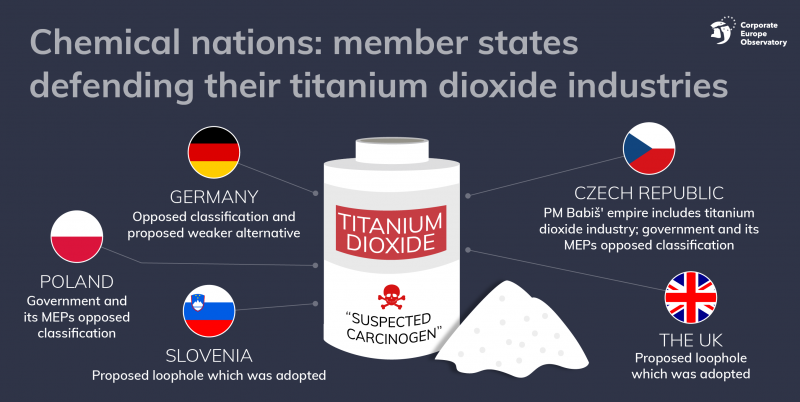

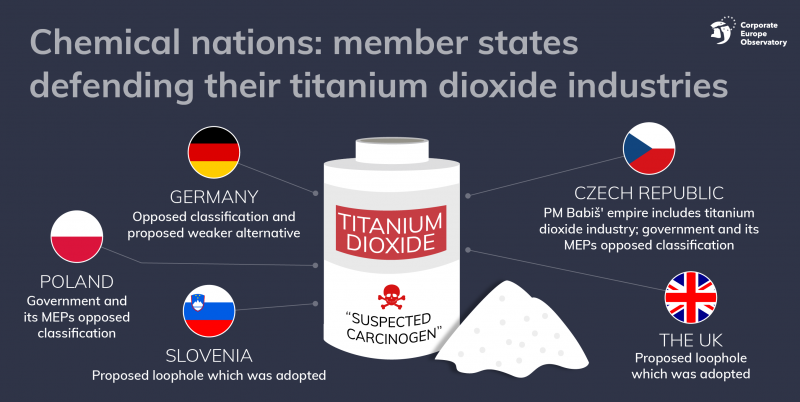

Chemical nations: how member states defend their dirty industries

The titanium dioxide lobby battle has just ended with a weak classification for this chemical recognised as a “suspected carcinogen”. Member states have been active in defending their industrial interests, at the expense of science and public health, and have achieved some wins. Below we expose these ‘chemical nations’, several of whom are led by authoritarian parties or leaders. Of particular concern is Czech Prime Minister Babiš' conflict of interest – his de facto business empire includes the production of titanium dioxide – and is the subject of an upcoming European Parliament plenary vote. SidenoteThe vote was due on Thursday 12 March but has now been postponed due to the coronavirus.

Background

Titanium dioxide is often found in commonly-used domestic substances such as paint, sunscreen, and toothpaste. However, the World Health Organisation’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has determined that the chemical is a “possible carcinogen for humans”. After a proposal from the French Government, in 2017 the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) was charged with providing a recommendation to the European Commission on the matter. This assessment proposed classifying all forms of titanium dioxide as a “suspected carcinogen” when inhaled.

Since then, the Commission has been presenting proposals to the REACH comitology committee (the committee for the European Regulation on Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals, consisting of officials from all member states) in an attempt to find agreement on whether and how to classify this widely-used but controversial chemical. But some member states, including those with significant chemicals industries, made clear their opposition to both the ECHA proposal and subsequent Commission attempts to reach agreement.

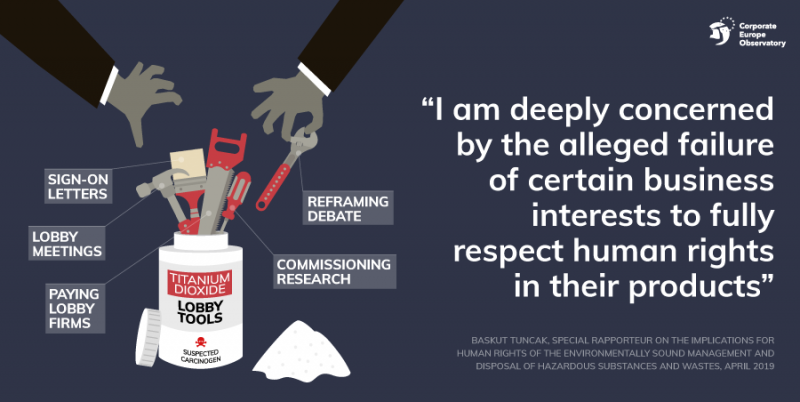

Industry lobbying has far outweighed the voices of NGOs and trade unions advocating for human health and a safe environment.

Moreover, industry lobbying has far outweighed the voices of NGOs and trade unions advocating for human health and a safe environment. Industry’s massive resources have enabled it to deliver repeated and coordinated lobby demands.

In October 2019, after more than two years of deadlock in the REACH committee, the Commission turned the proposed classification of titanium dioxide (alongside proposals concerning other chemicals) into a proposal for a delegated act. This new process meant that the Council of the EU (member states) and the European Parliament (MEPs) had a limited window of two months (later extended to four) to object to the proposal, which would essentially mean a rejection, or to let it go through.

Ultimately, the titanium dioxide classification will go ahead and be in force from October 2021, but below we look at how several member states, their lobbies, and MEPs tried to use this final opportunity to block the process.

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic has consistently opposed the proposed classification of titanium dioxide, both in the Commission-coordinated process focussed on the REACH committee, and then subsequently when the process moved to the Council of the EU. In November 2019 the Czech Republic, together with Germany, tried to mount an objection to the classification in the Council, although ultimately it did not attract enough support from other member states to pass.

Precheza is the only company in the Czech Republic which produces titanium dioxide. By its own admission, titanium dioxide (which the company calls pretiox) is Precheza’s most important product and it refers to its production technology as “Czech family silver”. Precheza exports up to 90 per cent of the 62,000 tonnes of pretiox it produces each year.

Precheza is owned by Agrofert which was founded by Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš.

Crucially, Precheza is owned by Agrofert which was founded by the current Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš. In fact Precheza is Agrofert’s most profitable subsidiary, with a profit of over €39 million each year, with 90 per cent of its sales coming from titanium dioxide. (Agrofert also owns DEZA, a chemical company which produces controversial chemicals including DEHP which is widely used as a plasticiser in every day products, but which causes developmental problems in children and infertility.)

Babiš the oligarch

Current Czech Prime Minister Babiš – a billionaire and the second richest man in the Czech Republic – made his fortune via Agrofert, a massive agricultural and chemical conglomerate. In 2011 Babiš created ANO, the Action for Dissatisfied Citizens as a populist and – somewhat ironically – “anti-corruption” party. Today ANO’s biggest donor is Babiš himself via the many companies he is connected to.

In February 2017 (when Babiš was Minister of Finance) the Czech Republic amended its law against conflicts of interest to prohibit members of the government (plus other officials) from having 25 per cent or more shares in any company that accepts subsidies and contracts from the state. Babiš had to find a solution to these new rules, nicknamed Lex Babiš, and ideally one that would still keep Agrofert close to him but that would also allow the company to receive subsidies and contracts from state institutions. His solution was to put control of his companies (Agrofert and SynBiol) into two trust funds controlled by his wife Monika and his lifelong close co-workers. But questions remain about the extent to which Babiš continues to benefit from Agrofert and investigations by Transparency International Czech Republic indicate that Babiš continues to be a primary beneficiary, and controller, of Agrofert.

For years Babiš has been under investigation for suspicion of fraud over EU funds that were aimed at small and medium businesses but which he apparently funnelled into building a personal mansion. But an even bigger scandal occurred last year when a European Commission audit found Babiš to have a conflict of interest over the EU subsidies received by Agrofert, and that the Czech Government should repay up to €17 million of EU subsidies received by the company over the previous two years.

A recent delegation of MEPs to the Czech Republic found evidence of official efforts to bury conflicts of interest; and two Czech MEPs on the delegation were called “traitors” by Babiš, leading to serious concerns about their personal safety. This delegation’s work will inform the upcoming European Parliament resolution.

Babiš is also the de facto owner of 30 per cent of the private media in the Czech Republic including the media group MAFRA, various newspapers, and the popular Radio Impuls. Babiš is accused of using his control over the media to push favourable messages, silence critics, and attack the opposition. As just one example, Corporate Europe Observatory’s board member Jakub Patočka and the media portal he works for, Deník Referendum, have been threatened with legal action after publishing exposés on Babiš’ corporate affairs in a book of investigative reportages called Zlutý baron ('The yellow baron').

Deník Referendum recently published an in-depth article about how Babiš built his business empire and how he is capturing the Czech state (including a focus on the role of EU subsidies). This forms part of a series Know your billionaires! published by the European Network of Corporate Observatories.

It’s not possible to say categorically whether the Czech Government’s opposition to the classification of titanium dioxide at the EU level is directly linked to Prime Minister Babiš’ ownership of the country’s only titanium dioxide producer, but it is clear that Babiš has a conflict of interest on this issue. After all, it is his ANO Government that decides the national position to be presented in Brussels.

More generally, there is evidence of how Babiš’ private interests influence Czech Government decision-making.

Titanium dioxide producer Precheza was fined for a chemical leak which occurred in the town of Přerov in October 2014. However, the initial fine of 7 million koruna (€270,000+) levied by regulators, was later lowered to half a million koruna amid suggestions of political interference in the regulatory process by the Environment Ministry. The Czech Environment Minister was Richard Brabec, who was also Babiš’ Deputy Prime Minister until April 2019, and formerly a manager at chemicals business Lovochemie, part of the Agrofert conglomerate. Brabec has denied interfering in the reduction of Precheza’s fine. Yet Deník Referendum has documented other examples of how regulators within the Czech state have suspiciously favoured Agrofert companies.

Notwithstanding any political patronage Precheza may enjoy thanks to its status in the Babiš empire, it has been actively lobbying against the proposed EU classification of titanium dioxide.

Precheza has been actively lobbying against the proposed EU classification of titanium dioxide.

Precheza is one of only eight members of the Titanium Dioxide Manufacturers Association (TDMA) which has been leading the lobbying against the classification and features heavily in previous Corporate Europe Observatory articles on this issue. TDMA has undertaken many activities in the lobby battle including a €14 million research programme, using lobby consultancy Fleishman-Hillard, and lobby meetings. In March 2019 TDMA members including Precheza wrote to the Commission seeking to avoid the classification of titanium dioxide.

Precheza was one of hundreds of industry lobbies which submitted a response to the Commission consultation on the proposed classification. It relied on familiar arguments used across the industry to dispute health concerns, and to argue that the classification will damage the industry.

Precheza is also a member of several Czech trade associations which have been lobbying on titanium dioxide at the EU level. For example in September 2019 300 business organisations signed a letter, coordinated by the TDMA, to ask for a delay in the classification by implementing an impact assessment, a demand taken straight out of the 'Better Regulation' lobbyists’ playbook. The letter was addressed to the Commission’s Secretariat General, going over the heads of the officials in DG Environment and DG Grow who were handling the classification process, and the signatories included the following associations, all of which have Precheza (and sometimes Agrofert too) as a member: the Association of Chemical Industry of the Czech Republic (SCHP ČR); the Association of Paint Manufacturers of the Czech Republic (AVNH); and the Czech Plastic Cluster.

SCHP wrote its own letter to the Commission in February 2019 and also submitted to the Commission’s consultation. It has also been publicly critical of the classification process and in September 2019 stated that it “plans to negotiate with representatives of the Ministry of the Environment” to highlight “shortcomings of the current classification process” and to present industry’s alternative proposal for an impact assessment. However, an impact assessment would only delay the process and would bring pro-industry economic arguments into a decision which should only be about the health and environmental consequences of a particular chemical.

So how far does the Babiš/ Agrofert/ Precheza connection stretch?

The European Parliament, like the Council, was also given an opportunity to object to the Commission’s proposed classification on titanium dioxide. Some MEPs were happy to take up this opportunity and Anna Zalewska MEP (ECR, Poland) drafted an objection using all of the industry’s usual arguments.

There are six MEPs from Babiš’ ANO party in the European Parliament and when the Zalewska objection was discussed in the ENVI committee in December 2019, ANO MEP Ondřej Knotek spoke on behalf of the Renew Europe (Liberal group). However Knotek had to make clear that while Renew opposed the objection, he himself supported the (pro-industry) objection, arguing that there was “no reason to question if the compound is toxic or not”.

The whole ANO delegation supported the objection when it came to the plenary vote in January 2020.

In fact, the whole ANO delegation decided to support the objection to the classification when it came to the plenary vote in January 2020.

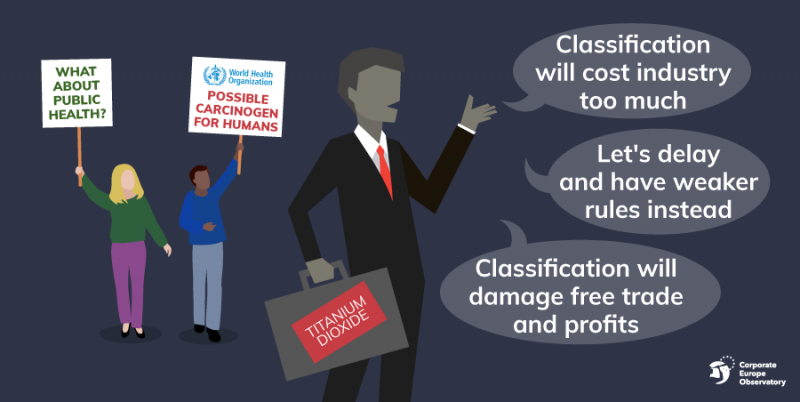

Corporate Europe Observatory approached Ondřej Knotek and the other five ANO MEPs to understand their rationale for voting in this way, and the ‘usual’ reasons were given by Martina Dlabajová MEP along the lines of: the Commission “probably abused” its powers when classifying titanium dioxide; the Commission did not follow Better Regulation processes and conduct an impact assessment; the classification is too broad; there will be negative impacts; there is an alternative way to manage titanium dioxide. These arguments are already familiar from previous industry statements.

When Corporate Europe Observatory asked two follow-up questions about Babiš’ connections to Precheza and whether the vote had been discussed with the Czech Government, Dlabajová told us: “All relevant information related to the vote on TiO2 objection are included in our previous response. We responsibly consider all relevant aspects in all votings.” (The full email exchange is available here). This reply can be interpreted in several ways, with the line, “We responsibly consider all relevant aspects in all votings” [emphasis added] perhaps presenting more questions than it answers.

Dlabajová also told us that they had been lobbied by chemical corporate lobby group CEFIC (and Czech environmental group, Arnika which supported the classification of titanium dioxide). CEFIC, the European Chemical Industry Council, is the parent organisation of the TDMA (of which Precheza is a member) and is arguably Brussels’ biggest lobby spender. CEFIC employs the lobby consultancy Fleishman-Hillard to the tune of nearly one million euros annually for work which includes lobbying on behalf of TDMA.

Fleishman-Hillard was contacting MEPs on behalf of TDMA to request a meeting to discuss the objection.

Fleishman-Hillard was contacting MEPs on behalf of TDMA in January 2020 to request a meeting to discuss the objection to the classification of titanium dioxide. Its email said “we understand the issue may come back in the plenary at the end of the month”, apparently showing that it knew MEPs were thinking to re-table the objection rejected by the ENVI committee. (A Fleishman-Hillard email to an (anonymised) MEP is available here.)

ANO MEP Martin Hlaváček

Martin Hlaváček MEP was first elected to the European Parliament in 2019 and according to his declaration of financial interests previously enjoyed a career at Philip Morris Products Switzerland on a salary of €20,000 a month (including dividend pay outs). He also worked for Czech business consultancy Triple M which focuses on agriculture policy. Triple M’s EU lobby clients are currently listed on the EU lobby register as the Agricultural Association of the Czech Republic, Food Chamber of the Czech Republic, Agrarian Chamber of the Czech Republic, and the Agricultural and food business initiative, although Czech sources indicate that the firm is now in administration. Nonetheless, it is surely a nice coincidence that Triple M’s former staffer now finds himself a member of the Parliament’s agriculture committee.

Whether in the Council, the Parliament, or the REACH Committee, Czech officials and ANO MEPs have been fully on board with the position of Precheza, owned by Prime Minister Babiš. This has resulted in a disgraceful conflict of interest situation, made all the worse as, at its heart, have been attempts to deflect the classification of a “suspected carcinogen”.

Poland

The Polish Government opposed the classification of titanium dioxide during the two-year REACH process and subsequently when the issue came to the Council in Autumn 2019.

Poland’s largest chemical producer is Grupa Azoty whose products include titanium dioxide. While Azoty is no longer a member of TDMA, it is still a business member of the chemicals lobby group CEFIC. Azoty has in the past been a client of EPPA, a lobby firm based in Brussels which today represents others in the chemicals field including Bayer and BASF. Azoty submitted to the Commission’s consultation on the classification of titanium dioxide, referring to it as “not an appropriate and proportionate measure”.

Polish MEP Anna Zalewska MEP (ECR) tabled the ENVI committee and plenary objections, to the classification of titanium dioxide, both of which were roundly rejected by large majorities although they did ensure a further two month delay in the process. Zalewska was supported by her Polish ECR colleague Joanna Kopcińska. Both MEPs are members of, and former ministers in, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS), the authoritarian right-wing governing party in Poland. PiS is a 'pro-coal' party known for its dubious record on environmental issues.

During the debate on the Zalewska objection, MEP Anja Hazekamp (Netherlands, GUE-NGL) told the ENVI committee that “I cannot support this objection which you know perfectly well has been written by the lobby”. Meanwhile a Socialist MEP, Seb Dance (UK, S&D) was subsequently quoted as saying: “The ECR’s attempt to delay the [titanium dioxide] classification from the Commission was a cynical attempt to pander to the interests of big corporations in the EU.”

"I cannot support this objection which you know perfectly well has been written by the lobby."

Corporate Europe Observatory contacted MEP Zalewska before publishing this article, to ask several question about her contacts with lobbyists on this issue and the extent to which they had assisted with the drafting of the objection text, but to date Ms Zalewska has not replied.

Authoritarian Right’s support for titanium dioxide industry

Aside from PiS and ANO MEPs, others from authoritarian parties have also been happy to wade in to the debate on the side of industry to oppose the classification of titanium dioxide. Lega MEP Angel Ciocca queried the classification via a written parliamentary question, reinforcing the impression that while Lega may try to appear critical of the enormous power of big business, in practice, it is happy to support business as usual.

Germany

Corporate Europe Observatory has previously documented how the German Government has been very active in defending titanium dioxide producers in the REACH committee process. The German Government was the architect of the strategy to oppose the proposed classification of titanium dioxide by suggesting the chemical should instead be referred to a much weaker, alternative process which would come up with ‘exposure limits’ for workplaces. An obvious flaw in this proposal is that it leaves freelance workers and consumers out of the picture entirely. SidenoteCorporate Europe Observatory has previously shown how effective industry lobbies have been at influencing the occupational exposure limit process, successfully keeping chemicals off the list of those to be regulated, or ensuring that the exposure levels set are as weak as possible. Industry recommendations for exposure levels via this process have, unsurprisingly, been consistently weaker than those proposed by trade unions.

Yet this alternative German proposal has been enthusiastically supported by many who oppose the Commission’s classification, and was included in the Zalewska objections in the European Parliament. German industry has been very active in supporting the proposal including these lobbies: German Social Accident Insurance (DGUV), German Toy Manufacturers’ Association (DVSI), German Paint and Printing Ink Association (VdL), and others. (Copies of the correspondence are available here.)

Germany has a significant titanium dioxide industry, and producer Evonik is a former member of the TDMA. Meanwhile German lobbies featured prominently in the letter to delay the classification by implementing an impact assessment signed by 300 industry groups including the employers’ lobby group BDI; chemicals giant BASF; the chemical industry association VCI; Evonik, and others.

Germany did not hesitate to raise an objection, alongside the Czech Republic.

When the classification process moved to the Council, Germany did not hesitate to raise an objection, alongside the Czech Republic, and apparently other states too. The issue was discussed by member state officials at the Council working party on technical harmonisation on 8 November 2019. Corporate Europe Observatory has requested the minutes and other documents relating to this discussion, but traditionally – and shockingly – such working parties have “neither an obligation nor a practice” to keep minutes of their discussions, preventing proper transparency of the discussions.

Nonetheless an industry lobby – the German Plastic Packaging Association – appears to have had good contacts in the room as soon after the meeting it reported that: “At the meeting of the Working Party on 8 November, Romania, Austria, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Greece, Poland, the Czech Republic and Germany confirmed during a heated 3 hour debate their opposition to the act. However, the active engagement by the Commission prevented that more Member States joined this group. Therefore, the qualified majority (16 Member States) was not met.”

Germany’s alternative, weaker proposal for handling titanium dioxide exclusively in workplaces became a rallying point for all those opposed to the Commission’s proposal and thereby helped to keep the Commission’s proposal as feeble as possible.

Slovenia and the UK

The Governments of Slovenia and the UK also made a key intervention in the debate on the classification of titanium dioxide during the lengthy approval process. Their 2018 proposal for a weak classification which excluded mixtures appears to have significantly influenced the Commission’s final proposal which confirmed this loophole, and led these two countries to eventually become reconciled to the final classification.

As previously reported by Corporate Europe Observatory, both Slovenia and the UK have significant titanium dioxide industries.

There were at least 17 contacts between the titanium dioxide industry and UK officials between July 2017 and March 2019.

We documented numerous contacts between the titanium dioxide industry and UK officials on this matter, numbering at least 17 between July 2017 and March 2019, including a ministerial visit to the premises of Cristal, a major titanium dioxide producer (now owned by TDMA member Tronox). TDMA member Venator is another major producer of this disputed chemical with bases in the UK.

In Slovenia Cinkarna Celje is one of the biggest chemical companies and a member of the TDMA. Its primary source of income is titanium dioxide, it employs 900 people, and has sales of about €150 million a year. It was among many industry bodies to have submitted to the Commission’s consultation process to oppose the proposed classification.

An extensive article in the Finance Business Daily in Slovenia from January 2020 raised questions over the links between government decision-making on the proposed EU classification and Cinkarna. It reported that the government office charged with developing the Slovenian position, the National Chemical Bureau, consulted Professor Damjana Drobne from the Biotechnical Faculty of the University of Ljubljana. She had been a member of the EU’s NanoSafetyCluster which looked at titanium dioxide and in April 2017 Drobne had been nominated by the Slovenian National Chemical Bureau as a national expert to attend an EU expert group (CARACAL) meeting to discuss the classification of titanium dioxide.

Drobne has told Corporate Europe Observatory that she was involved in the UK-Slovenia proposal as she was the “scientific advise[r] to our National Chemical Bureau as a member of their scientific nano-working group”. It is understood that the National Chemical Bureau held one “informative” meeting with representatives of the Chamber of Commerce and Cinkarna during the classification process.

Separately however Cinkarna had also commissioned Drobne’s team at the University of Ljubljana to review “existing scientific publications on the effect of titanium dioxide on biological systems”. In an email to Corporate Europe Observatory, Drobne called this a “knowledge transfer activity” and said that the “work was not published, but it is composed of many of our scientific publications on [titanium dioxide] and biological effects”.

Cinkarna said: “By engaging experts, we also participated in the preparation of opinion foundations of Slovenia as an EU member state”.

However according to its 2018 annual report, Cinkarna said: “By engaging experts, we also participated in the preparation of opinion foundations of Slovenia as an EU member state”. Remarkably, according to the Finance Business Daily, the government office saw no conflict of interest in the professor working for both industry and the government.

Drobne told the journal that “I personally ‘fight’ for titanium dioxide and safe use”. In February 2018 Drobne spoke at a conference in the Czech Republic, organised by the chemical industry lobby SCHP (discussed above), outlining the position of Slovenia as opposed to the proposed classification of titanium dioxide. Her online CV lists three companies with whom she has had “cooperation” including Cinkarna, a cooperation she has described as “lectures [and] participation in international projects, where Cinkarna is an industrial partner”. She also spoke at both the 2017 and 2019 industry-heavy TiO2 world summits. The full exchanges with Professor Drobne are available here.

It seems clear that once the Commission had weakened its own proposal to exclude mixtures, along the lines of the UK-Slovenia proposal, both countries were able to accept the classification. Another Slovenian company with an interest in the classification process, Helios, told the Finance Business Daily that the Slovene-British proposal was an “important step in finding a positive compromise”.

As a result of the UK-Slovenia proposal, a loophole remains for consumers regarding the information that they will receive on titanium dioxide products.

Nonetheless, and as a result of the UK-Slovenia proposal, a loophole remains for consumers regarding the information that they will now receive regarding titanium dioxide products. Liquid and solid mixtures will only be labelled with a warning about the dangers of inhalation, but not that the product contains a “suspected carcinogen”. This can be contrasted with the cancer-warning labelling of titanium dioxide products such as sunscreen and some sprays in California.

E171, the other titanium dioxide lobby battle

The titanium dioxide industry has been fighting on two fronts at the EU level. Additional to the classification process detailed above, last year the French Government announced a ban on the titanium dioxide food additive (called E171) starting in January 2020. Industry lobby groups have been up in arms about it and have demanded that the Commission and member states prevent the French Government from taking this step, despite the increasing numbers of industry players who are already phasing out the chemical from their food products. There is a possible relationship between consumption of E171, which is purely used for aesthetic reasons, and a higher risk of colorectal cancer. A number of member states have tried to oppose the French ban, although the Commission has confirmed that while it will not take action to prevent the French ban, it will also not propose such a measure EU-wide. It has said that it will await the results of European Food Safety Authority studies into E171 due later in 2020. The French ban on E171 is safe – for now.

Conclusion

Titanium dioxide classification has been controversial, not because of the lack of evidence to support a classification, but because it is so widely-used, which has led industry to fight hard to protect its profits. But this also means that exposure to this chemical is widespread.

As we have seen, this lobby battle over titanium dioxide has been a sorry saga of member states defending national industries which manufacture products recognised as “suspected carcinogens”. Traditionally when the European Chemicals Agency makes a recommendation, it is normally a foregone conclusion to accept and implement it.

A toxic alliance between some member states, industry, some MEPs, and others, has disrupted the titanium dioxide classification process.

But in this case a toxic alliance between some member states, industry, some MEPs, and others, has disrupted the process. By proposing loopholes, championing weaker alternative processes, and using the Commission’s own Better Regulation agenda, this alliance has ensured that, while a classification has now gone ahead for titanium dioxide, it is far weaker than the science indicates it should be. And even then, industry is apparently contemplating legal action over it.

This is truly toxic nationalism. And in the case of Czech Prime Minister Babiš whose Agrofert empire includes substantial interests in titanium dioxide, there has been a clear conflict of interest, effectively operationalised by Czech officials and ANO MEPs participating in the regulatory process at the EU level.

Is the writing on the wall for toxic oligarch Babiš? Perhaps not yet. But with an imminent European Parliament plenary vote on his conflicts of interest, and the European Council facing legal action over the role that Babiš plays in that forum, it is time that all other EU institutions reflect on the consequences of having a billionaire oligarch as an EU member state leader – and take action.

This story also makes the case, once again, for proper transparency of member state positions in comitology and Council forums. Only then can citizens, journalists, and civil society understand and expose the lobbying influences which are disrupting public interest decision-making.