How corporate lobbying undermined the EU’s push to ban surveillance ads

Despite the EU's talk about regulating the digital sphere, we uncover how Big Tech has successfully waged a major lobbying campaign to prevent a ban on their extremely profitable model of intrusive surveillance advertising. However MEPs still have a chance to turn some of this around.

This week Members of the European Parliament will be voting on the Digital Services Act, including an opportunity to ban 'surveillance' advertising. This ad system is at the core of the business model of companies such as Google and Facebook and other digital advertisers, involving extensive tracking and profiling of internet users. These profiles are then used to target users for anything from selling them shoes to influencing their vote.

In October 2020 MEPs collectively agreed on the need to regulate ‘surveillance advertising’ more strictly in favour of less intrusive forms of advertising that do not require any user tracking. They also recommended that the Commission should assess a phase-out leading to a ban of this type advertising practice. Unfortunately, after a year of intense negotiations and even more intense corporate lobbying, the proposal MEPs will vote on looks much weaker than the original call for a ban. As the Parliament prepares to start trilogue negotiations with Council and Commission, this Thursday’s plenary vote will be MEPs' final chance to reverse their position.

This week’s vote marks the end of intense parliamentary discussions over online content moderation, responsibilities of online markets, and higher transparency and accountability of very large online platforms (and who gets to be defined as one). The European Parliament's Committee on Internal Market and Consumer Protection (IMCO), who led the process, finally achieved compromise in late December 2021. The text includes positive developments such as increased transparency over algorithms, and an end to 'dark patterns' that manipulate online users into giving consent to tracking.

But one particularly sore issue remained unresolved: the failure to agree on a ban for surveillance advertising. For Human Rights Watch, the proposal failed to “address the surveillance-based advertising business model that dominates today’s digital environment“, a business model it says is “fundamentally incompatible with human rights”.

Corporate Europe Observatory spoke with several parliamentary insiders about this process. All of them pointed at one main reason for the failure to ban surveillance ads: corporate lobbying, which had been aided by a particularly complex and frustrating negotiating process.

Their testimonies illustrate the pushback by tech, retail, and publishers' lobby groups that managed to sow doubt over the necessity of such a ban. Martin Schirdewan, MEP of the Left Group, told Corporate Europe Observatory that at the start of this process there was a “feeling that there could be a progressive majority” but then the pushback began.

Surveillance advertising and the Digital Services Act

Surveillance advertising – also known as tracking or behaviour ads – relies on the massive collection of data on people, from the websites they have visited, their search engine queries, the videos they watched, to the type of device they use, their location, other apps they have downloaded, purchasing history, etc. Users’ online lives are mined for information and are then used to build up a user profile. These profiles can have a variety of personal information, things that can be simply observed and others that are inferred: from age, to economic status, political views, religion, sexual orientation, mental and physical health, etc. This data is then used to micro-target users with advertising.

For Human Rights Watch, the proposal failed to “address the surveillance-based advertising business model that dominates today’s digital environment“, a business model it says is “fundamentally incompatible with human rights”.

Google and Facebook are the undisputed winners of online advertising, controlling several steps of the 'supply chain' Sidenote In June 2021, the Commission’s Competition department opened up separate investigations into the advertising business of both Google and Facebook. When opening a new investigation into Google’s advertising business, Commissioner Vestager noted that “Google collects data to be used for targeted advertising purposes, it sells advertising space and also acts as an online advertising intermediary. So Google is present at almost all levels of the supply chain for online display advertising”. and are often described as an ad duopoly. It is at the core of their business model: in 2020, Google racked in US$147 billion in advertising revenue, while Facebook took in US$84 billion. But there are a wide number of other actors in this system, including advertisers, the ad agencies that help them, media publishers that have come to rely on advertising income, data brokers that sell information to complete users’ profiles and, finally, ad exchanges that connect advertisers to publishers.

Criticism of surveillance ads has been growing in recent years. First and foremost due to the extreme data collection (essentially, surveillance) it requires and for the way it undermines people’s data protection and privacy. Personalized ads have also been linked with other societal ills, including manipulative political campaigns, the exploitation of people in vulnerable states, and discrimination.

Importantly, surveillance advertising creates a need for online platforms to maximize the time users spend online in order to collect an increasing amount of data that they can later commercialise. This ‘attention economy’ has been linked to issues like automatic amplification of incendiary content – often controversial content which makes users stay online longer and engage more.

Surveillance advertising can be extremely profitable – especially for Google and Facebook – but it has one big problem: people don’t like to be under constant commercial surveillance. Polls conducted in 2021 in France, Germany, and Norway showed that more than half of respondents felt negatively towards their personal data being used for advertising. Sidenote A Yougov poll commissioned by Global Witness in 2021 found that 57 per cent of respondents did not want their personal data being used to target them with commercial or political ads, a further 26 per cent did not want their personal data being used for political ads. The Norwegian Consumer Council commissioned a separate Yougov poll in Norway found more than half of respondents had negative responses to ads based on personal information. And when people are given a choice to actually opt-out, they mostly do it. In 2018 the Dutch Public Broadcaster NPO gave its users a real choice to not be tracked and 90 per cent of users opted out. In 2021 Apple gave its users the option to not be tracked and users chose it 96 per cent of the time.

Ad-tech executives used to argue that people liked tracking advertising because they didn’t want to see irrelevant ads. Given the direction of public feeling on this issue, that argument has mostly dropped out of usage.

the EDPS concluded that “given the many risks associated with online targeted advertising” the EU Institutions should “consider additional rules going beyond transparency”.

Advertising was discussed as one part of the much bigger Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act, two complementary proposals meant to be the EU’s offensive to rein in the power of Big Tech. The European Commission’s Digital Services Act laid out concerns that online ads can create societal problems, including by creating a financial incentive for illegal or harmful content and activities or by possibly enabling discrimination. The Commission further lays out that very large online platforms carry extra risks because of the scale of their advertising systems and their ability to target users “based on their behaviour within and outside that platform’s online interface".

Yet, unlike the European Parliament, the Commission’s proposal only went as far as asking for more transparency for users to be able to able to ascertain who is behind the ad and which parameters were used to target them. Very large online platforms are further obliged to create ads archives to allow external scrutiny and research into “emerging risks brought about by the distribution of advertising online”.

However, for the EU’s independent data protection authority, the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS), this does not go far enough. In its assessment of the Commission proposal, the EDPS concluded that “given the many risks associated with online targeted advertising” the EU Institutions should “consider additional rules going beyond transparency”. The EDPS backed the European Parliament in calling for “a phase-out leading to a prohibition of targeted advertising on the basis of pervasive tracking”.

And it wasn’t alone: in November 2021, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) – the body that brings together representatives of the EU national data protection authorities – joined the calls for a phase-out leading to a ban of surveillance advertising. It also added that the “profiling of children should overall be prohibited”.

The opinion of the EDPS and the EDPB are particularly relevant as they are the bodies responsible for ensuring the application of the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Their support adds weight to claims that going beyond the current data protection rules is needed to address the systemic problems of this ad system.

After the European Commission published its proposals – which, contrary to the call from MEPs, were limited to transparency requirements – 25 Members of the European Parliament created the Tracking-free ads coalition. Liberals, socialists, greens, and left MEPs got together with the support of civil society organisations and private firms. The coalition highlights two main problems with the surveillance ads system: that it harms journalism – by diverting advertising income away from media outlets into the tech giants – and harms people by providing financial incentives to disinformation and other types of toxic content.

Christel Schaldemose, the lead MEP responsible for putting together the Parliament’s position on the Digital Services Act, joined the coalition and publicly supported a ban. Yet this growing momentum soon faced counter-pressure from corporate lobbyists.

The DSA lobbying front

Logs of MEPs lobby meetings back up claims that there was intense lobbying pressure on the Digital Services Act overall. In the year that followed the European Commission’s proposal in late 2020, 613 encounters were logged as discussing the Digital Services Act Sidenote Corporate Europe Observatory analysed logged meetings that took place between 16/01/2020 to 30/11/2021 that included keywords associated to the Digital Services Act. In case any of the meetings included more than one actor, we logged them as separate, hence we use ‘encounter’ rather than ‘meeting’. In the absence of a central Parliament meetings repository, meetings information should be taken as indicative. The meetings data was scrapped from the individual pages of Members of the European Parliament by Parltrack. . That means a rate of 1.7 meetings a day, without any breaks.

Yet we know this is not a complete list. Only 63 MEPs disclosed having meetings to discuss the DSA in this period time. Among the more notorious absences Sidenote As per rule 11 of the European Parliament’s rules of procedure, MEPs responsible for authoring reports or chairing committees are obliged to proactively disclose their lobby meetings. in the list, given their roles, are the author of the Legal Affairs Committee opinion, Geoffrey Didier (EPP); author of the Women’s Rights and Gender Equality opinion, Jadwiga Wiśniewska (ECR); and the author of the Transport and Tourism opinion, Roman Haider (ID).

Corporate Europe Observatory got in touch with Didier, Wiśniewska, and Haider but received no reply.

With the data that was made available, we can quickly see that Big Tech firms easily dominated with most access; Google tops the chart, followed by Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft. Their interests were further reinforced by the industry associations that represent them like the Interactive Advertisers Bureau (IAB), dot.europe and the Computer & Communication Industry Association (CCIA).

But they also reveal a much wider spread of actors that sought to influence the negotiations, including media and publishers like ZDF, ARD, the European Broadcasting Union, telecoms companies like Vodafone and AT&T Communications, retail and marketers like the World Federation of Advertisers and EuroCommerce.

Civil society organisations were also present, especially HateAid, European Digital Rights (EDRi), the European Consumer Organisation (BEUC), and the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). However, civil society organisations were outnumbered by commercial actors overall.

The Digital Services Act covers an immense number of issues and these lobbying meetings wouldn’t all have involved mentions of the limits to surveillance ads. There were other issues at play that raised lobbying attention: consumer associations clashed with big online marketplaces over proposed new accountability requirements; media and publishers clashed with disinformation activists and tech lobby groups over the impact of a possible exception for media from content moderation by the platforms; and platforms pushed back against increased transparency and scrutiny over their algorithms.

Yet, according to Parliament sources, online advertising quickly became the most intense issue at the table.

Industry lobby associations led the pushback

A source close to the Parliament negotiations told us that there had been lobbying against a surveillance ads ban ever since the 2020 report recommending that the European Commission should assess of “options for regulating targeted advertising, including a phase-out leading to a prohibition“. Yet, the lobbying seems to have grown increasingly intense as more details of the possible final position of the Parliament became known.

Paul Tang saw this pushback as “a gigantic lobbying opposition, especially before the Summer [2021], even before we were working on amendments”.

Martin Schirdewan, Left MEP and the group’s lead for the DSA and DMA, told us that “Big Tech companies tried to reach out to MEPs even at a quite early stage, but it intensified later on with the negotiations as the fault lines and negotiation issues were clearer”. From his perspective, once “there was a clear progressive effort to ban targeted advertising”, Big Tech, and its lobby associations focused in on this issue.

Dutch MEP, and co-founder of the Tracking Free Ads coalition, Paul Tang saw this pushback as “a gigantic lobbying opposition, especially before the Summer [2021], even before we were working on amendments”.

What followed was a flurry of industry coalition lobby letters, one on one meetings, and an aggressive advertising campaign. The main messages were clear: banning surveillance advertising will 'hurt small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs)' – the go-to argument for Big Tech and its allies that want to re-frame policy discussions away from discussions of its own business model – and it will 'hurt media plurality' by affecting the reliance of some media on revenue from surveillance ads.

Besides, according to the lobbyists, the EU already has 'enough' privacy rules in places, we 'only' need more transparency (but not 'too much' transparency either!). And finally, they argue, this ban has not even been 'costed' according to the 'Better Regulation' agenda. The EU’s industry-friendly Better Regulation agenda foresees that legislative proposals should be preceded by impact assessments to attempt to assess their economic and social costs. These types of impact assessments have been criticised by organisations like the New Economics Foundation as, in practice, it is often easier to “evidence the short-run ‘costs to business’ than broader non-marketable goods like long-run environmental, human health, and societal welfare”.

For people following privacy debates this might give a sensation of deja vu. That’s because this was the same strategy used for years to weaken and stall the ePrivacy Directive reform. You can read our analysis of that lobby battle here.

This lobbying frenzy became most evident after Schaldemose’s draft report was published in May 2021. The MEPs proposal’s did not include a full out ban but instead it would require platforms like Google and Facebook to turn off user tracking by default. If a user wanted, they could opt-in to tracking and personalisation. While not a ban, this could already be an immense setback for the tracking advertising industry, as the NPO and Apple examples mentioned above show that when given a real choice users tend to stay out of tracking.

With the publication of Schaldemose’s report, the industry associations lobbying seems to have gone into overdrive. The Computer and Communications Industry Association (CCIA), for instance, put out a statement signed by other Big Tech industry bodies like EuroISPA and Developers Alliance, Digital Poland and the Finnish Federation for Communications and Teleinformatics. The statement damned various elements Sidenote The CCIA also criticised new stay down obligations for illegal or fraudulent products for marketplaces and measures for algorithmic accountability. of Schaldemose’s report including the measures on surveillance ads. According to their statement, “the proposal for an opt-in for targeted ads will undermine a key aspect of the digital ecosystem which allows thousands of small businesses to reach and connect with customers across Europe”.

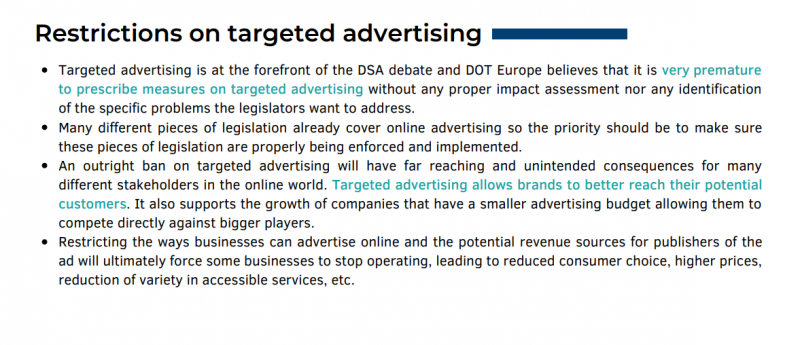

In an e-mail sent to MEPs, Dot Europe, another tech lobby group representing companies like Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft, argued that the Commission’s proposal was enough to address the DSA’s goal and that changes proposed by MEPs Sidenote DotEurope opposed MEP’s proposals to restrict targeted advertising but also new content moderation obligations, measures interfering with platforms’ design (likely new rules against ‘dark patterns’), and rules for the platforms’ content ranking systems. Read more about dark patterns and ranking systems. would make the DSA “too complex to implement for companies and detrimental for the EU economy as a whole.”

Like the majority of corporate lobby letters we have analysed, in order to appeal to MEPs, DotEurope instead supports transparency requirements as proposed by the European Commission. But not 'too much' transparency of course.

A few months later in July 2021, the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) – the main lobby group for the ad-tech industry representing Google and Facebook but also other advertisers, media and publishers – sent a letter to EU policy-makers signed by over 45 companies, industry associations, and media groups. This asserted that a ban would mean such a 'reduction of income' to businesses and media that it would mean that they would 'no longer' be able to provide those services to users, and other content would be moved behind paywalls. In their view, a ban would also mean that SMEs and big brands alike would no longer be able to “provide the right marketing messages at the right audience at the right time”.

The IAB ends by praising the current privacy set of rules of the EU and recommends focusing on getting them enforced. The IAB is also the body behind the advertising Transparency and Consent Framework used by the majority of the ad-tech industry (including Google) to justify their data practices. This framework is expected to be deemed unlawful according to the General Data Protection Regulation in an upcoming decision by the Belgian Data Protection Authority. Early findings by the Authority had argued that this framework failed to comply with principles of “transparency, fairness and accountability, and also the lawfulness of processing” and, further, that “does not provide adequate rules for the processing of special category data (eg health information, political affiliation, sexual orientation etc) — yet does process that data”.

In September 2021, the pushback scored an important win: Commission Executive Vice-President Vestager said publicly that she did not support a ban, saying that “for many smaller businesses, it is really important to be able to find their potential customers, and where I come from, it is legitimate to advertise, it is legitimate to try to find the people with whom you want to communicate”.

The reasoning that banning surveillance advertising would be disastrous for SMEs is not shared by everyone though. The Digital Services Act Observatory, a research project by the Institute for Information Law (IViR) at the Faculty of Law University of Amsterdam Sidenote Supported by Open Society Foundation. Note, Corporate Europe Observatory is also supported by the Open Society Foundation. You can find our full funding sources here - https://corporateeurope.org/en/who-we-are , published a critical overview of the DSA by Ilaria Buri and Joris van Hoboken. When it comes to the advertising requirements, Buri and Hoboken question the Commission’s reasoning noting that “the Commission’s assumption that smaller businesses would be affected by the transition to a different advertising model might have also played a role in shaping the DSA’s rules on online advertising. While this idea is defended with great conviction by the relevant platforms, recent studies cast major doubts on the effectiveness of this advertising model and conclude that less privacy-intrusive advertising schemes can actually bring more opportunities for both advertisers and publishers (with less money spent in middlemen).”

A new YouGov poll of SMEs in Germany and France commissioned by Amnesty Tech and Global Witness reveal that SMEs might not be as comfortable with surveillance advertising as the platforms want us to believe. According to the poll, the vast majority of respondents (79 per cent) “want to see big online platforms – such as Facebook and Google – face more regulation in terms of how they use people’s personal data and target users with advertising”. Further, 69 per cent SMEs responded that “while they were uncomfortable with Facebook and Google’s influence, they felt they had no option but to advertise with them due to their dominance of the industry”.

Tracking, behavioural or targeted ads?

Retail lobby associations also got involved. In October 2021, Ecommerce Europe, Independent Retail Europe and EuroCommerce who represent members like Carrefour, Spar, Rewe, and Ikea, issued a joint statement setting out its positions on targeted advertising. Their main points boiled down to: targeted online advertising is already regulated “in more suitable legislation”, a ban would hurt SMEs, innovation and growth. To argue this they referred to two Facebook reports.

As the final committee vote approached, the lobbying letters became more detailed. In December 2021 the Classified Marketplaces Europe (CME) sent MEPs their detailed feedback on amendments. One of them states:

“We strongly oppose NEW Article 24.2, which goes beyond the GDPR requirements on consent options from end-users, would pose a severe threat to advertising revenues which is an important revenue channel for financing classifieds business models. At the very least it has to be aligned with the GDPR by replacing the word “refusing” with the word “withdrawing” as stated in Art. 7 para.3 GDPR.”

One of the mainstays of the lobbying pushback was the blurring of lines of what was at stake. The retail industry, for instance, argued that “targeted advertising” could be beneficial to consumers as they would then get to see more relevant information and that such targeting was comparable to real-life situations. They say:

“targeted advertisement is not a phenomenon limited to the online world. The advertisements we see on TV or in printed magazines for example are also always targeted to a specific audience ie the readers or viewers of these media formats. In addition, in brick-and-mortar retail, when a shop consultant consults a customer on which suit to buy, he or she will also screen the customer and make recommendations based on his or her size, style and the perceived budget."

The comparison is misleading. Not only do people not expect their shopkeepers to guess (infer) their size or their budget, the example also minimises the depth and pervasiveness of the tracking done by adtech – the shopkeeper and the TV ads don’t follow users around in their normal lives, taking notes of the places they visited, the charities they supported, their home address, their friendships, their religion, etc.

a source told CEO that they were particularly struck by how the corporate lobbying campaign simplified the issue, “a lot of the messaging was that you either have personalisation or you have nothing at all"

For Jan Penfrat, Senior Policy Advisor at the European Digital Rights network (EDRI), this type of confusion stems from the mis-leading use of the terms targeted advertising. In fact, several people told Corporate Europe Observatory that one of the main lobby messages constantly conflated targeted advertising with surveillance advertising, or in its technical name, behavioural advertising.

A parliamentary source told CEO that they were particularly struck by how the corporate lobbying campaign simplified the issue, “a lot of the messaging was that you either have personalisation or you have nothing at all. And that is really not true. Contextual advertising is a thing and it’s what we have been used for centuries. A lot of people have mixed personalised and targeting and some people might have done it willingly. Could be that it was actual confusion or that it was spin.”

Most lobbying letters we analysed at once diminish the risks of surveillance advertising while also pitching it as the only type of possible online advertising. Yet, proponents of the ban argue that there are alternatives, including contextual advertising. Contextual advertising stands out because it does not rely on pervasive user tracking, instead the ads would be targeted according to the content or the specific search query. This would still allow the ads to be targeted, for example a user searching for headphones would be delivered ads for headphones, and ads for headphones would be placed next to music articles.

Currently, this type of advertising represents only a small share of the total digital market, but one example has been hailed by the privacy-minded camp, that of Dutch public broadcaster, Nederlandse Publieke Omroep (NPO). In 2018, the NPO decided that it wanted to fully obey the new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) by giving its users a real choice to not be tracked: 90 per cent of the users opted out. As a response, the NPO developed its own contextual advertising system in-house. This model bucked negative expectations and actually led to increased revenue. According to the broadcaster, this was largely due to the fact that this way they could cut out all the middlemen including Google, which were taking a large cut of the advertising income generated by the broadcasters’ content. And the advertisers didn’t lose out either: the broadcasters’ results showed that the ads were performing just as well if not better.

The overlapping lobbying of Big Tech and media publishers

It is no secret that EU publishers are not dying of love for Big Tech. Media publishers often spearhead efforts against the tech companies, especially when it comes to copyright issues but also over competition and liability. But there is one area where their interests seem to be aligned so far: advertising.

This was visible for instance during the so-far-unsuccessful discussions to reform the ePrivacy Directive. You can read our analysis of that lobbying battle here.

Yet in January 2021 a letter from Mathias Döpfner, chief executive of publisher Axel Springer, to President Von der Leyen seemed to mark a shift. Döpfner described at length what he saw as the problems created by the online ads systems, especially its massive extraction of personal data for behavioural targeting and the dominance of the advertising systems by Facebook and Google which was hurting publishers. The letter contains an impassioned plea to the President to prohibit platforms from “storing private data and from using that data for commercial gain. This must become law”.

Döpfner even alerts the President of the pushback that should be expected from the platforms saying:

“The platforms will tell you that you are destroying their business model by doing that. That is not true. It will only get a little weaker. Like the publishing houses and like every blogger (the publishing houses of the future), the platforms will still be able to monetize their reach. Or like every trader or wholesaler, the platforms can still sell their products and services. But billions will flow back into the hands of thousands of publishing houses, artists and retailers. To companies who ensure customer loyalty thanks to the quality of their products, and not by monitoring their behavior.”

To many, this open letter seemed like a turning point. Yet, the promise of a policy shift from publishers’ seems to have never materialised. Döpfner’s media conglomerate, Axel Springer, is one of the signatories to the IAB’s letter opposing a ban on surveillance ads.

The European Publishers Council, of which Axel Springer is a member, also opposed a ban. So did other media industry associations like New Media Europe and EMMA-ENPA. They argued a ban would lead to a massive drop of income to publishers and could lead to media outlets closing or moving their content behind paywalls. Instead, they argue “the problem lies with the way platforms collect and use data, rather than with the practice of targeted advertising itself.”

Parliamentary insiders confirmed to Corporate Europe Observatory that news and media publishers were actively lobbying against the ban. Though we were also told that later on in the process, publishers’ lobby groups moved their attention on to media exception from content moderation Sidenote Publishers have asked the EU Institutions to amend the Digital Services Act to ensure that platforms are not able to censor or demote their content. However, disinformation experts and civil society organisation have warned that such an exception could open a loophole and allow the disinformation to continue spreading. A good summary of the discussion here. issue.

Shadow lobbying

MEP Tang told us that Big Tech firms weren’t “as vocal” when it came to one on one meetings. Other parliamentary sources confirmed they also did not receive many requests by Facebook or Google directly but instead “organisations that represent or claim to represent other actors. Organisations that claim to represent SMEs and startups, but that once you do a bit of digging, they are at least funded by Google and Facebook.“

Corporate Europe Observatory found traces of lobbying against the ban by associations like Allied for Startups, and national level associations such as NL digital and SME Connect. Allied for Startups has launched a #DSA4Startups campaign which warns of the impact of the proposal on business users. Their research for this was conducted by Oxera which acknowledges to have received “comments and funding from Allied for Startups’ corporate board members” (page 4). Allied for Startups corporate members include Google, Facebook and Amazon. SME Connect also deserves extra attention as it is not a business association but rather a platform to bring together MEPs and SMEs. Their work though is financed by companies like Facebook, Amazon, and Google. SME Connect was very active in the surveillance advertising debate, setting up a Coalition for Digital Ads of SMEs and sending lobby letters to MEPs opposing limits to tracking ads, including possible limits to dark patterns.

Another coalition of startups was recently created just to lobby against possible bans – Targeting Startups. The coalition includes the same lobby groups that represent Big Tech (CCIA), advertisers (IAB europe and the Advertising Information Group), and business chambers that include big tech as members or funders (Dutch Startup Association, Allied for Startups, Slovak Alliance for Innovation Economy).

A parliamentary insider offered a possible explanation for this. Surveillance advertising is an “uncomfortable issue to lobby on because it is negative, companies always prefer to lobby on positive topics”.

We could add too that MEPs are likely to be more sympathetic to impacts on SMEs rather than on multinational corporations. Big Tech's invocation of SMEs to protect what are in reality its own business interests is no accident: Google’s leaked lobbying memo explained how the tech giant wanted to ‘reset the political narrative’ by, among other things, focusing on how the DSA threatened benefits for consumers and businesses. Part of that work was to be done by mobilising European businesses.

Though it’s not that the giants went completely absent. Google, for instance, sponsored a series of exclusive debates hosted by the think-tank European Policy Center, including one on ‘targeted ads’ that asked “How can the DSA/DMA boost media pluralism and growth in the EU?”.

In November 2021, just before the committee discussions entered their final stages, Google sent an email to MEPs asking for meetings during the following plenary session in Strasbourg. It wanted to discuss the “possible ban on targeted advertising that the EP is currently considering in both DSA and DMA files”. Google offered MEPs a meeting with the Head of its “responsible digital advertising policy team in Europe” and it wanted to “to present positive elements of targeted advertising as well as point out negative consequences of a possible ban for the wider digital ecosystem (consumers, publishers and advertisers)”.

Expensive advertising campaign

Meanwhile, during this whole period, Facebook seemed to be running a parallel strategy. The tech giant has led an immense online and offline advertising campaign framing the company – and its surveillance ads – as essential for SMEs. Lobbycontrol has estimated that Facebook’s spending on print advertising in Germany alone since December 2020 is worth about €6.8 million (gross advertising expenditure without accounting for possible negotiated prices). One of these campaigns has focused on how SMEs depend on Facebook, including targeted ads. That campaign alone is estimated to be worth €2.5 million.

Lobbycontrol’s figures are just estimates but even still they only show a glimpse into the total ad spending Facebook has incurred in this period. This type of advertising campaign has also taken place in the Netherlands and Belgium. Facebook has, for instance, been sponsoring Politico Europe Morning Tech newsletters for months, ‘powered’ several editions of Euractiv’s Digital Brief (though they have taken turns with Google) and have placed full page ads in several editions of the Parliament Magazine, a publication aimed specifically at MEPs and distributed inside the Parliament. Anyone in Brussels can currently see similar ads in the Brussels Airport.

These have been matched with intense advertising on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Facebook’s ad repository shows that the Facebook EU Affairs team and Facebook Inc placed 109 ads that were flagged as dealing with “social issues, elections or politics”.

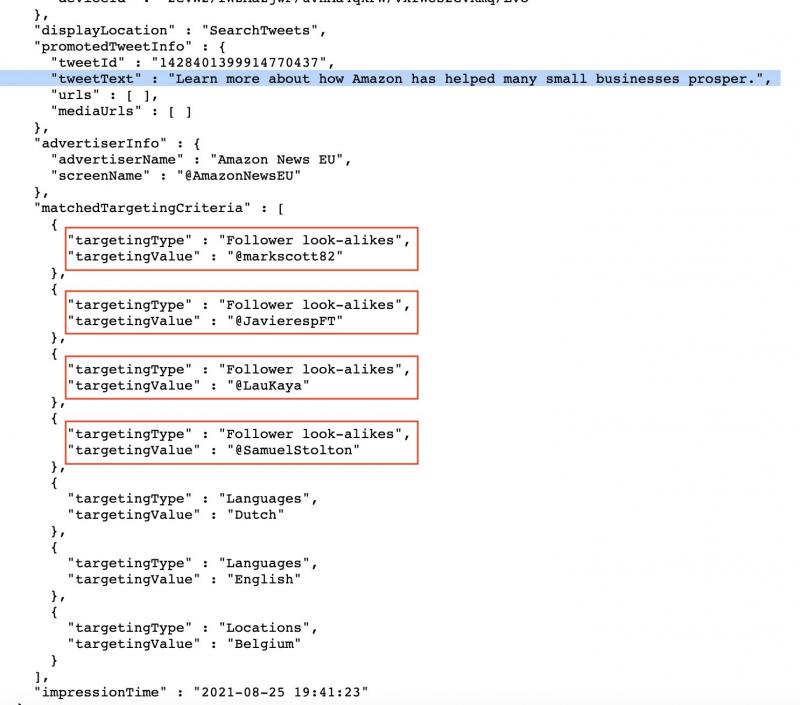

And the social media platform wasn’t the only one using these types of tools. Both the CCIA , the IAB and Amazon pushed these ads, especially on Twitter. They were targeting a specific crowd: either people that were labelled as academic or policy-makers or by looking for audiences with similar profiles to those of tech policy journalists at Politico Europe. In Germany, a similar targeting took place: accounts similar to those of German Ministries.

Was there an impact?

By the time IMCO held its final vote, the proposal for a ban and even for obliging platforms to set default settings to 'no surveillance' were off the table. There was not enough support.

For Penfrat of the European Digital Rights network, this result was at least in part shaped by lobbying. The corporate pushback managed to sow enough doubt in some MEPs that were on the fence, making them move into the no-ban position. A parliamentary source talked about how the corporate lobbying led to a politicisation of the issue around two camps: a pro and an anti. In their view, that wouldn’t have been the case without the lobbying effort.

The corporate pushback managed to sow enough doubt in some MEPs that were on the fence, making them move into the no-ban position.

According to all the accounts Corporate Europe Observatory has heard of the lobbying battle, the SME argument seemed to be particularly effective. A parliamentary source even described how at a meeting, an MEP recited numbers of how surveillance ads helped SMEs in a way that seemed they were merely reading Facebook’s ads aloud. Some MEPs echoed the lobby message clearly in public – as in this example of Slovak EPP MEPs which hit every single talking point of industry.

MEPs also offered issues with the negotiation process itself: it was arduous, too many issues to deal with in not enough time, and advertising didn’t get enough airtime. Regulating surveillance advertising is complicated and can be confusing. Given these conditions, the corporate strategy had enough space to be successful.

Yet not all is lost. While no ban or default opt-in was agreed in IMCO, the Committee did achieve some progress including the limits to dark patterns which currently make it difficult for users to opt out of tracking. Other parts of the Digital Services Act (DSA) show progress, in spite of the pushback from Big Tech. These include new rules to allow public scrutiny into platforms’ algorithms and obliging the platforms to provide recommender systems that are not based on profiling. These are positive steps. The key difference here seems to be that Big Tech failed to mobilise other businesses behind those issues.

Even more, MEPs have tabled amendments to the IMCO text to be voted on this week – including a possible full ban on surveillance ads and new proposal to at least ban tracking ads based on sensitive personal data (collected and inferred).

So MEPs still have a chance to turn this process around and, at least, achieve improvements on the status quo. Even beyond the DSA, there is a clear public rejection of the surveillance advertising model, and one can expect that renewed challenges against it will continue to appear.

However, it should be noted that this story is the perfect reminder that in spite of EU decision-makers speaking tough against Big Tech, industry's immense lobbying budgets and the web of third parties they finance, can still have an impact and limit the biggest challenges to the tech giants. We already saw similar dynamics happening in the ePrivacy Directive. In that case, leaks of internal memos and documents made public via court cases showed Amazon and Google bragging of their lobby impact. Google allegedly claimed to have been successful “in slowing down and delaying” the proposal by “working behind the scenes hand in hand with the other companies".

It wouldn’t be shocking if we were to see more such leaks in the future dealing with how the companies tamed the push to ban surveillance ads in the Digital Services Act.

Policy-makers will need to reflect on these experiences and revise the way they deal with with Big Tech and its allies. They should be sceptical of those lobbying them: question their funding sources, denounce any type of wrongdoing/ non-transparent / unethical lobbying they face, and wise up to some of the classic narratives typically used by industries who don't want to be regulated.

MEP Martin Schirdewan stated that in this process he would not be meeting Big Tech lobbyists or organisations that were funded by them. In his perspective, the views of Big Tech were abundantly clear from the stream of lobbying papers and participation in public debates. Other policy-makers should consider whether to follow suit.

At the very least, they should adopt the practice of proactively seeking out the views of those who have less resources: small and medium enterprises, independent academics, civil society, and community groups. And policy-makers should consider favouring public hearings to lobbying meetings, so the firms can be held to account for their claims.