Stay always informed

Interested in our articles? Get the latest information and analysis straight to your email. Sign up for our newsletter.

Europeans are exposed to alarmingly high levels of harmful chemicals and pesticides that also harm ecosystems, soil, air, and water. But promises to tackle these substances via the Green Deal are being shelved. New evidence now reveals how Big Toxics and its allies have used misleading narratives to try to weaken the concept of ‘essential use’, to create regulatory loopholes for their hazardous products, and ultimately derailing the Commission’s flagship chemicals reform.

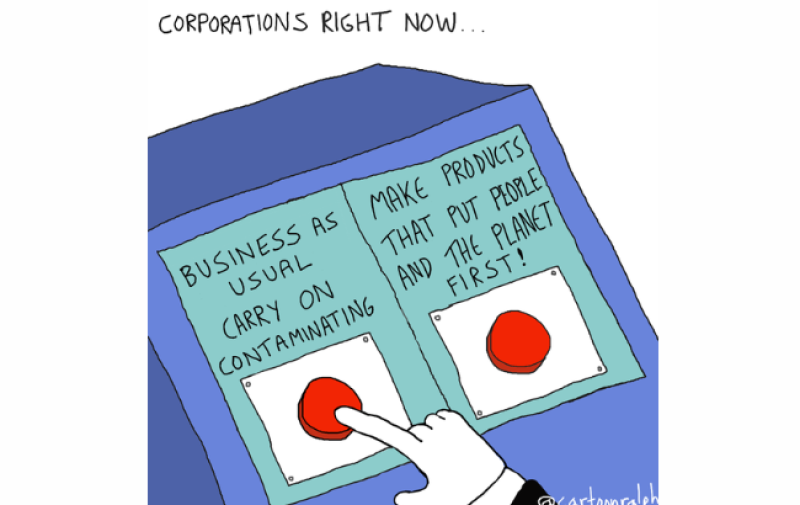

As we approach the end of the von der Leyen Commission the postponement and even abandonment of major Green Deal commitments to tackle hazardous chemicals and pesticides has pleased both industry and the political right. As part of this trend the European Commission’s proposal to reform existing chemicals rules has been kicked into the long grass, with disputes about one of its key components – the ‘essential use’ concept – apparently at the “heart” of the Commission’s “political impasse”. Introducing an ‘essential use’ concept could really help with streamlining the regulation of hazardous substances in everyday consumer products, from childcare articles to textiles, and with the substitution to safer alternatives. But corporate lobbies have been fighting back hard to demand major loopholes. In doing so they are trying to undermine a sensible measure aimed at responding to the growing toxics crisis and the bad decision-making by industry that has allowed hazardous substances in consumer products in the first place. Below we explore five of industry’s key, but misleading, arguments about ‘essential use’.

The Commission’s flagship 2020 Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability (CSS), part of the Green Deal, promised to define criteria for ‘essential uses’. As part of this work the Commission contracted a consultancy (Wood, now WSP) to produce a study, building on workshops and a consultation. Accordingly, the essential use concept has the potential to “protect the environment and human health from most harmful substances by facilitating the phase out of non-essential uses and therefore preventing potential human and environmental exposure to the most harmful substances.”

The CSS took its lead from the UN’s Montreal Protocol on ozone-depleting substances that first defined the concept of essential use. This 1987 treaty banned chemicals that were damaging the ozone layer, with the exception of a few instances when these substances were to be used in an ‘essential’ way. Overtime the treaty has driven both a major recovery of the ozone layer and a transition to much safer alternatives, even for uses previously found to be ‘essential’. This switch to safe and sustainable substances should be a key objective of the essential use concept. But Big Toxics and the wider industry of chemical producers and users are keen to broaden and weaken the definition of what is ‘essential’ to exclude as many hazardous substances as it can from a ban.

Essential use is closely linked with another CSS proposal to extend the ‘generic approach to risk management’ (GARM) in order to streamline the elimination of hazardous chemicals SidenoteThese include those which cause cancer, gene mutations, affect the reproductive or endocrine system, or are persistent and bio-accumulative. In the CSS the Commission also pledged to assess the inclusion of further properties of chemicals which affect the immune, neurological or respiratory systems and chemicals toxic to a specific organ. in consumer products, from toys and food packaging, to cosmetics and detergents, and in professional uses. GARM allows for a simplified decision-making process to restrict chemicals which assumes an inevitable exposure when harmful chemicals are used in consumer products or those used by professionals such as painters, hairdressers, and cleaners. GARM is based on the precautionary principle, a concept enshrined in the EU treaty. Where scientific data does not permit a complete evaluation of the risk of a substance, the precautionary principle can be used to withdraw products which are likely to be harmful. The precautionary principle is closely associated with a hazard-based approach to regulation based on potential harm; the alternative, risk-based approach is far more lenient on the use of hazardous chemical substances and is favoured by industry.

A precautionary approach is vital because the EU’s REACH regulation SidenoteREACH – the EU’s main chemicals regulation from 2007 – is the registration, evaluation, authorisation and restriction of chemicals. It aims to improve the protection of human health and the environment through the better and earlier identification of the intrinsic properties of chemical substances. takes a long time to restrict or ban hazardous substances – sometimes a decade or more – and meanwhile they remain on the market.

Both the extension to GARM and the introduction of an essential use concept are eminently sensible ways to make progress in tackling the toxics crisis that threatens human health and the environment. European citizens are exposed to ‘alarmingly high levels of chemical substances’, linked to cancer, infertility, obesity, and asthma, and these substances also contribute to the collapse of insect, bird, and mammal populations. Yet there is no collective political recognition of the need to curb the flow of hazardous substances.

@CartoonRalph

Now Corporate Europe Observatory’s research shows how the chemicals industry has heavily lobbied the Commission over the extension of GARM and essential use while they have been developed behind the scenes. In response to our access to documents requests, the Commission’s industry department (DG Grow) produced over 100 documents on these topics (covering October 2020 to March 2023) including lobby letters and briefings, meeting minutes etc, while DG Environment highlighted a further 40, analysed below. Further documents from the Secretariat-General of the Commission have also been scrutinised, alongside published industry position papers.

Originally, the Commission’s communication on the essential use concept was to be published as part of the package to revise the REACH chemicals legislation, originally expected in 2022, then delayed to 2023. However, a combination of corporate lobbying, Commission in-fighting, and right-wing political pressure now means that the REACH revision will not now be published by this Commission. And a media report from October 2023 blamed internal Commission disputes over essential use as being “at the heart of the political impasse” on the REACH revision. But while REACH has now been formally postponed, officials are still working to finalise the essential use communication and it could still be published before the EU elections.

Below we assess five of the key lobby arguments spouted by industry on the essential use concept (EUC).

Perhaps the central argument from industry voices opposing the EUC – or at least trying to substantially weaken it – has been that it should be balanced by considerations of so-called ‘safe use’. In industry’s eyes, this would enable its existing hazardous substances to continue to be used in everyday consumer goods so long as they can be shown to be ‘safe’.

But this is a very misleading argument. ‘Safe use’ is pretty much the system we have today, which is clearly not sufficiently protective. Today’s system does not prevent hazardous chemicals from being included in babies’ pacifiers or other childcare articles, ‘forever chemicals’ in dental floss, or known carcinogens in lipstick lids, to give just a few examples. Balancing essential use with ‘safe use’ would be a licence to carry-on contaminating.

@CartoonRalph

Additionally, ‘safe use’ implies that we can accurately know what will happen to hazardous substances when included in everyday consumer products throughout their whole lifecycle, including during their production, use, and ultimate disposal. But that is a myth. Ultimately, an emphasis on ‘safe use’ would still mean more production and distribution of hazardous substances. Swedish NGO ChemSec has questioned whether ‘safe use’ is the “evil twin” of essential use.

Industry is fighting hard for the ‘safe use’ concept and has set up The Alliance for Sustainable Management of Chemical Risk (ASMoR) to campaign on its “common goal to ensure that safe uses of hazardous substances remain permitted”. It includes various industry associations such as the American Chamber of Commerce to the EU (AmCham EU), the International Bromine Council, the Nickel Institute, and others. Between them these trade associations have a declared annual lobby spend running into several million euros although, at the time of writing, ASMoR itself is not in the register, despite having its own website and clearly being an active lobbyist in its own name. According to a briefing for Commission officials, the contacts for the ASMoR secretariat are staff at Hanover Communications which is 16th on LobbyFacts’ list of the biggest lobby consultancies in Brussels. Hanover does not list ASMoR as a client in its declaration to the EU lobby transparency register, although, for example, ASMoR member the Nickel Institute is listed.

ASMoR has been highly critical of the Commission’s study on the EUC by consultants Wood/WSP which, while noting the strong support for a ‘safe use’ element from industry elements, did not recommend the inclusion of ‘safe use’ criteria itself. Nonetheless ASMoR’s industry groups insist their own approach is “pragmatic and targeted”. In a June 2021 meeting with DG Grow the alliance promoted the ‘safe use’ concept so as not to ban what it calls “safe products”. Another meeting with DGs Grow and Environment in November 2022 reinforced the message. BusinessEurope, BASF, and Eurometaux have all argued along similar lines. SidenoteBusinessEurope’s own briefing on the EUC states that “the aspect of safe use should be considered in this new [essential use] concept”. Along similar lines, BASF, the world’s largest chemical producer, had a November 2022 meeting with the DG Grow director-general in which it presented its “proposals to reach CSS objectives while remaining competitive”. These included to “Complement existing processes using safe-use concept with essential use derogations”. Meanwhile Eurometaux has demanded that the Commission introduces “exemptions for substances in safe uses with minimal exposure” in its lobby meeting in February 2023.

The European Risk Forum, now rebranded the European Regulation and Innovation Forum (ERIF), is supported by various chemicals companies and trade associations including BASF, Dow, Syngenta, the European Chemicals Industry Council (CEFIC), and PlasticsEurope, as well as two major lobby firms. It used to have several tobacco industry members. ERIF is a major proponent of the so-called innovation principle, an industry-invented concept which stands in contrast to the established precautionary principle, and its publication on the EUC critiques the idea saying “There is no attention to safety, safe enjoyment of benefits or specific exposures”. ERIF further argues that implementation of the “essentiality concept” by the EU will “create strategic risks”.

All in all, there has been a deluge of lobbying by chemical producers and downstream industries which use chemical substances in their products, to argue that their products are safe and that ‘safe use’ should be used to avoid what they consider to be the unnecessary restrictions that would follow from emphasising essential use. But ‘safe use’ is a myth when we are talking about substances which are harmful (that is, carcinogenic, mutagenic, harmful to reproduction, bio-accumulative, endocrine-disrupting, persistent etc) as safety thresholds cannot be reliably derived, making industry’s approach deeply problematic. Additionally, scientific analysis of the health and environmental impacts of hazardous chemicals throughout their whole lifecycle, including end-of-life disposal, is constantly emerging, and something viewed as ‘safe’ today may not be considered safe in the future. As a result, a precautionary approach requires us to start with the assumption that all hazardous chemicals should be removed from consumer products.

Jargon buster |

|

|

Industry says … sell, sell, sell existing toxic products |

Public interest groups say … we need toxic-free products |

|

Safe use: A mythical argument which assumes that it is possible to derive safe levels of hazardous substances throughout the whole lifecycle of everyday consumer goods, to enable such substances to still be used. This is essentially the current status quo system, which has failed to get hazardous substances off the market |

Essential use: A concept originating in the Montreal Protocol which says that hazardous substances in consumer products must be banned except in very limited cases when their use is essential to society and no acceptable alternatives exist |

|

Innovation principle: An industry-derived lobby tool, the ‘innovation principle’ aims to ensure that new rules and laws should consider and address the impact on ‘innovation’ which is often reduced to short-term economic interests and ‘competitiveness’, and which risks compromising on other areas such as health and environment |

Precautionary principle: When scientific data does not permit a complete evaluation of the risk of a substance, the precautionary principle can be used to withdraw substances which are likely to be harmful, on health and environmental grounds. Enshrined in the EU treaty |

|

Risk-based approach to regulation: Industry’s preferred approach, which implies that the risks of hazardous substances can be assessed and managed enabling the hazardous substance to be used. This approach is really slow, requiring case by case, specific assessments of exposure and risk levels |

Hazard-based approach to regulation: This has a different starting point, that known hazardous substances are considered too dangerous to be used safely and should not be authorised. This generic approach then brings in considerations of risk and exposure to make regulatory decisions |

@CartoonRalph

A second industry narrative is that their products are essential, thereby demanding an EUC definition which would, by default, prevent them from being restricted. Particularly vociferous in articulating this demand are the fragrance and cosmetics industries, no doubt aware that however hard they argue, hazardous substances in lipsticks and perfumes cannot be justified as necessary for health, safety, or the functioning of society.

For example, meeting with the Secretariat-General of the Commission in September 2022, the International Fragrance Association (IFRA) presented that “Fragrances respond to essential consumer needs in daily products for health, wellness and hygiene” and put forward their concerns that “the concept of ‘essential uses’ could be too narrowly defined without taking into account the importance of fragrances”. In a meeting with industry commissioner Thierry Breton in October 2022 Cosmetics Europe, the industry lobby group, argued: “Cosmetics are essential to consumers, as they bring wider societal benefits to their health, self-esteem, well-being and the quality of life”. But a much broader group of downstream users have also been arguing this point and demanding exemptions for whole sectors including the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations and the Downstream Users of Chemicals Co-ordination Group. SidenoteThe Big Pharma lobby the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) lobbied DG Grow in July 2022 and argued that all “authorised pharmaceutical product[s] would have to be deemed to fulfil the essentiality criterion” on the basis that they had already been authorised (under separate legislation) and arguing that pharma products are not “interchangeable”. Meanwhile the lobby group the Downstream Users of Chemicals Co-ordination Group (DUCC, which includes IFRA, Cosmetics Europe, as well as associations representing detergents, paints, and pesticides) has warned that the “elimination of a substance with no alternatives for an application leads to elimination of entire product categories”.

We should not be brain-washed about the essentiality of certain products and the substances contained within them: it’s a no-brainer that products that we ingest, play with, wash our clothes in, or squirt on our skin should not contain hazardous substances. Consumer products such as childcare articles, textiles, furniture, clothes and shoes, food contact materials, personal care, cosmetics, luxury and many other categories should not include harmful substances, by default, unless the substance is shown to provide a specific essential value to society. If the Commission really gets to grips with hazardous substances in everyday products, even compromising on the performance of these products would be a small price to pay for action to tackle the toxics crisis.

An additional plank of corporate lobbying on the EUC concerns when and how in the assessment process the essentiality question should come in. Obviously it makes sense to assess essentiality early in the process of regulating a substance: if the use of a hazardous chemical is not essential for society, in accordance to the criteria, then the restriction should move ahead rapidly. But of course industry sees it very differently, wanting to keep chemical substances (even harmful ones), and the products that contain them, on the market for as long as possible.

The lobby group Downstream Users of Chemicals Co-ordination Group (DUCC, which includes IFRA, Cosmetics Europe, as well as associations representing detergents, paints, and pesticides) has argued that the EUC should be a “complementary tool for decision-making, the last step in the process, not the main driver for regulatory decisions”. BASF and BusinessEurope have argued similarly. SidenoteBASF has said the EUC should “complement existing processes” and BusinessEurope has said it could be used to “complement the existing risk-based regulatory approach”. But this is exactly the opposite of what the EUC is supposed to be used for, which is to streamline decision-making rather than slow it down further. This industry lobbying exposes how it has been trying to manoeuvre the EUC into an extremely limited side role, one that would have to run alongside other criteria such as socio-economic.

The European Chemicals Industry Council (CEFIC), Brussels’ biggest lobbyist, has further argued that the EUC should be applied “on a case-by-case analysis of individual uses” and “without excluding entire industry sectors”, even though this is not on the agenda anyhow. The EUC was labelled as one of CEFIC’s five main concerns about the proposed revision of REACH in a lobby meeting with Environment Commissioner Virginijus Sinkevičius in November 2022. BASF has said that the EUC should be evaluated “on a use-by-use basis, no fast-track process”, while 3M the chemical producer told DG Grow in a September 2020 meeting that the EUC “could not replace a proper impact assessment process and could not be used to bypass a proper risk assessment”, even though this is exactly what GARM and the EUC are supposed to do, in order to get hazardous substances off the market more quickly.

These arguments are pretty ironic considering industry’s usual demands to cut so-called bureaucratic red tape and to have regulatory clarity and predictability! Case-by-case analyses result in a slow regulatory process, and just when the Commission has finally recognised the need to speed up the removal of hazardous substances from the products we use. And if the EUC is only “complementary” to existing criteria, it will significantly reduce its value. Such an approach would maintain the existing structural bias of socio-economic analyses which over-emphasise the short-term negative impacts on industry profits while ignoring the benefits for health and environment – and indeed for industry itself – of a transition away from hazardous products.

Consideration of essential uses was not explicitly included in the universal PFAS restriction proposal SidenotePer- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a large class of thousands of man-made chemicals containing carbon-fluorine bonds which are one of the strongest in organic chemistry. They are hard-wearing and persistent, meaning they resist degradation, hence their nickname ‘forever chemicals’. that was presented by five member states in January 2023 (and which is based on the present REACH rules and is not dependent on the postponed REACH revision). The PFAS restriction did not include the EUC because the Commission has not yet brought forward its own definition and guidance on how it should be applied.

Nonetheless, it is a constant refrain in PFAS industry lobbying that ‘forever chemicals’ are essential in various applications in order to build support for permanent exemptions or long term derogations from the proposed ban on ‘forever chemicals’. For example, note how in a short op ed major PFAS polluter Chemours uses the word “essential” three times to defend PFAS, and elsewhere defends PFAS in construction and other sectors as also “essential”. Solvay, HydrogenEurope, AmCham EU and other corporate lobbies also defend PFAS as essential. Many defenders of PFAS argue that they are irreplaceable substances which cannot be substituted with non-hazardous alternatives.

Yet many of these claims of essentiality, in order to secure exemptions to the ban, are disputed. ChemSec says only about eight per cent of the total production volume of fluoropolymers (a sub-category of PFAS) goes towards the “essential” examples often-cited by industry of renewable energy, semiconductors and pharmaceuticals. And companies are already finding replacements for PFAS in these and other sectors too. It it is vital that both the EUC communication and the PFAS restriction have a full emphasis on the substitution of hazardous chemicals with safe alternatives so as to phase out all harmful chemicals.

@CartoonRalph

The award for the most brazen lobbying on the EUC must go to ExxonMobil. The fossil fuel giant, part of the Big Toxics lobby – for decades associated with misleading claims about the climate crisis – was reported to have told DG Grow in a February 2022 lobby meeting organised by AmCham EU that: “Essential use should be left to the market ‒ otherwise we will see many unintended consequences. Having a committee decide on essential use is ideology in action and spells the end of the market economy ‒ which has brought so many benefits. This is in effect anti democratic i.e. we the regulators know better than the market economy and public on detailed uses of substances – and we see literally today where this thinking can take us.”

The minutes of this meeting do not record if and how Commission officials responded to this diatribe, but Exxon’s ‘leave it to us’ rhetoric flies in the face of the factual evidence of the toxic pollution crisis affecting people and environments around the world. If the world had left dealing with ozone-depleting substances to industry instead of to the Montreal Protocol, would we really have seen the major progress in ozone layer recovery? Clearly not.

Industry has had decades to make better decisions about what substances they produce and include in the products they sell to us. And too often those decisions have prioritised profits over people and the planet. It’s time to hold industry to account for the decisions they have made to use hazardous chemicals in the products that they sell to us, and for them to use the essential use tool themselves for better decision-making about what they put in the products that we buy.

Industry has a great deal of scepticism about the EUC. Summing it up, BusinessEurope has written “The EU business community stresses that the EUC represents a departure from the current risk-based regulatory approach and remains unconvinced of its added-value at this stage.”

Corporate lobby pressure on the essential use concept, the extension of GARM and other key components led to the von der Leyen Commission’s “political impasse” and its regrettable failure to produce the promised legislative proposal to revise REACH. This has set back much-needed action on the toxics crisis. But other coverage has indicated that the Communication on essential use could still be published, separate to the REACH proposal, and is being actively worked on.

As this article has shown, industry lobbying has been intense and has clearly struck a chord with some pro-business allies in the Commission. It is imperative that when the essential use communication is finally published such pressure has not been allowed to hollow-out the ambition of what should be an important tool to get hazardous substances out of consumer products and to facilitate the transition to safe substances as quickly as possible.

Big Toxics and their industry allies will always demand a low-ambition regulatory environment in order to maximise the sales of their products, and the so-called ‘safe use’ concept and other demands aimed at derailing essential use, are a new front in this lobby battle. As a result, industry’s hefty financial lobby firepower and political reach will continue to pose a serious threat to public interest decision-making.

To tackle this, decision-makers should introduce a lobby firewall which, while permitting industry to submit evidence via open consultations and hearings, then protects policy-makers from further corporate lobbying so that they can take decisions that are truly in the public interests of health and environment.

Today Corporate Europe Observatory has written to the EU institutions about the unregistered lobbying of ASMoR, The Alliance for Sustainable Management of Chemical Risk, and asked them to investigate, including the role played by the lobby firm Hanover Communications.

Last month the European Commission finally published its communication on the essential use concept, available here. As it is only a communication, it does not have the status of law, so its success will depend on how well it is incorporated into and implemented through different chemicals rules and regulations. We can expect to see future lobby battles when the essential use concept is applied to specific regulations.

The EU lobby transparency register secretariat has now replied to our complaint about ASMoR being unregistered. It has confirmed that "the activities highlighted would indeed warrant, for purposes of full transparency, the registration of those alliances in the Transparency Register in their own name". It asked ASMoR to register and it has now done so here. In addition, the Commission has told us that "As a further step, the Secretariat is looking into the relationship between Hanover Communications and ASMoR to ensure the availability of transparent information in the registrations concerned, as applicable."

The EU lobby transparency register secretariat has now informed us that Hanover Communications International has updated its registration to include ASMoR as a client and the related revenues and EU legislative files for their activities.