Stay always informed

Interested in our articles? Get the latest information and analysis straight to your email. Sign up for our newsletter.

As politicians get ready to cosy up with Big Toxics at a private event in a chemicals factory to discuss a new 'European Industrial Deal', Corporate Europe Observatory looks at how the Green Deal's proposals to reduce and replace toxic substances that harm health and ecosystems, have been delayed and sidelined. This is the result of chemicals lobbying including an industry-commissioned study that has scaremongered over the impacts of new regulations.

On 20 February, the Belgian Presidency of the EU is hosting a high level corporate event at the premises of BASF’s gigantic chemical factory in the port of Antwerp. Thus the shameful tradition of corporate capture of EU presidencies continues, with the Belgian Government a willing accomplice.

Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo will join the European Commission President, regional political leaders, and corporate leaders to launch a declaration for a ‘European Industrial Deal’. The chemicals industry, led by the trade lobby the European Chemical Industry Council (CEFIC) will be out in force among other intensive energy users. Green groups and local organisations have not been invited.

The event gives succour to the narrative widely promoted by the industry – particularly in response to the Green Deal – that the chemicals sector needs support, is ‘overburdened’ with regulation, and that its economic needs should be prioritised over action on the toxics and biodiversity crises and damage to human health and ecosystems.

This narrative has been boosted by a CEFIC-commissioned ‘impact assessment’ which was widely covered in the media and promoted to decision-makers. Such studies are an increasingly important part of the corporate lobby tool box, and the CEFIC study made huge claims for the chemicals that were to be affected, and the job and economic losses to follow, from the Commission’s ambitious Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability (CSS), part of the Green Deal. While these claims were later disputed, nonetheless the study likely contributed to the postponement of the proposal to reform the REACH regulation SidenoteREACH – the EU’s main chemicals regulation from 2007 – is the registration, evaluation, authorisation and restriction of chemicals. It aims to improve the protection of human health and the environment through the better and earlier identification of the intrinsic properties of chemical substances., a key component of the CSS.

This delay comes despite the urgency of tackling the toxics crisis and of speeding-up decision-making to get toxic substances off the market. Ironically, this urgency is very evident at the port of Antwerp, already responsible for 10 per cent of Belgium’s carbon dioxide emissions, with local communities also confronted with pollution from PFAS ‘forever chemicals’. SidenotePer- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a large class of thousands of man-made chemicals containing carbon-fluorine bonds which are one of the strongest in organic chemistry. They are hard-wearing and persistent, meaning they resist degradation, hence their nickname ‘forever chemicals’. In fact PFAS pollution in Belgium is higher than anywhere else in Europe.

Tomorrow’s event is a prime example of the privileged access of big business, including the Big Toxics sector, to decision-makers in Brussels and across member states and could not provide a better example of why we urgently need toxic-free politics.

The European Chemical Industry Council, or CEFIC, says it is “the voice of the chemical industry in Europe” and for years has topped the LobbyFacts list of the biggest EU lobby spender, with a declared annual lobby spend of €10.4 million, and an overall budget of over €40 million. With 89 different lobbyists, 22 European Parliament passholders, and over 75 high-level lobby meetings with the von der Leyen Commission, there is scarcely a chemicals issue on which CEFIC does not lobby at the EU level. Within CEFIC are bespoke lobby groups, working on PFAS as well as other hazardous substances. CEFIC’s members include the big toxic polluters Bayer, Chemours, ExxonMobil and national chemical lobby associations such as Verband der Chemischen Industrie (the German association, VCI) which has a history of hyperbolic warnings about chemicals regulation and the Belgian chemicals lobby essenscia, with whom this event is co-organised.

One of CEFIC’s most important members is surely BASF, the biggest chemical producer in the world and an industrial behemoth in Germany. As Corporate Europe Observatory reported last year, BASF enjoys enormous political access and its connections cross party lines and stretch ‒ via Berlin ‒ from the regional to EU level. Its multi-million euro lobby budgets at the EU and German levels and its active network of industry allies, including VCI, have helped ensure that EU regulatory reform, including on the much-needed and now postponed revision of the REACH regulation of chemicals is as slow as possible. BASF has been heavily criticised for its production of hazardous chemicals and pesticides including PFAS, its massive use of fossil fuels, its historical tax avoidance, its human rights record, and other areas. According to BASF, its plant in Antwerp is the largest integrated chemical production site in Belgium and the second largest BASF production site in the world. BASF’s well-connected chief executive officer, Martin Brudermüller, is also the President of CEFIC (as well as playing several other roles such as chair of the European Round Table for Industry’s Committee for Competitiveness & Innovation, and is likely to be prominent at the Belgian presidency event).

European citizens are exposed to ‘alarmingly high levels of chemical substances’, linked to cancer, infertility, obesity, and asthma, and these substances also contribute to the collapse of insect, bird, and mammal populations. In the light of the toxic pollution and biodiversity crises, the climate crisis, and the risk to the planet’s natural boundaries, regulating hazardous substances is urgent. And yet as a result of industry lobbying and scaremongering, and the parroting of industry messages by right-wing politicians, the process is being derailed. This cosy meeting in Antwerp must be seen as a clear example of the high-level corporate capture of EU and member state decision-making by the chemicals lobby.

The event will be hosted at BASF’s chemical production site at the port of Antwerp, and is co-organised by CEFIC and its Belgian member essenscia. Sixty or more high-ranking industry leaders are expected to participate, alongside Belgian Prime Minister De Croo, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, and regional political leaders from Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany. It is being organised in direct liaison with De Croo’s office “under the auspices” of the Belgian presidency.

The Belgian federal Environment Ministry has been left entirely out of the loop, yet preparations have been underway for quite some time. The event was already being discussed in a lobby meeting in October 2023 between CEFIC and the Commission’s Industry department, DG Grow. Originally the event was billed as a “European chemical industry summit: a business case for Europe” by the Belgian EU presidency event.

But latterly the event has shifted in focus, apparently at the behest of von der Leyen, with more intensive energy-using sectors, including steel, pharma, and cement, now joining the chemicals industry, to demand an Industrial Deal.

There is a long and ignoble history of EU presidency countries accepting corporate sponsorship and it is remarkable that the Belgian Presidency would choose to include such a corporate-friendly event in its programme. The Belgian Government’s own guidelines for presidency sponsorship say it should not go ahead with events if “the nature and/or content of the sponsorship proposal or the nature of the activities of the party concerned are or could be detrimental to the reputation, dignity, principles, objectives or intended results of the Belgian EU2024 Presidency or pose a reputational risk to the Council or the EU”. It seems obvious that the presidency’s “reputation” and “dignity” will be damaged by this event.

Tomorrow’s event represents a major coup for CEFIC and an outcome of the chemical industry’s lobby strategy and narrative building in recent years.

For this event feeds into the story that the chemical industry has been weaving for years, most recently in the light of the Green Deal: the sector is ‘overburdened’ with regulation, especially those promised as part of the CSS and Farm to Fork; this and recent geopolitical developments such as high energy costs threaten to lead to EU deindustrialisation as the sector is driven overseas; the sector is crucial to the development of an EU green economy and its digital ambition. Much of this has been echoed by other intensive users of energy, over many years; and therefore the sector needs support, especially on energy prices.

Despite the fact that the chemicals industry has enjoyed steady growth in the past 10 years or more SidenoteAccording to Eurostat in September 2023, the EU’s total sold production of chemicals reached €872 billion in 2022, €335 billion more than in 2011 and the highest value since that year. Total sold production of chemicals has been increasing steadily since 2011, with an annual average growth rate for sold production of chemicals at 4.5 per cent. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20230920-2 , this messaging has been repeated by many right-wing politicians at national and EU levels, including German politicians from the CDU-CSU parties who have been prominent in opposing the revision of REACH and calling for a moratorium on the implementation of the Green Deal since 2022. This call has been picked up by the right-wing European People’s Party and heard at the highest levels.

In May 2023 De Croo attracted heavy criticism from green groups for a speech where he undermined the REACH revision and called for a pause on the biodiversity element of the Green Deal (the nature restoration law). French President Emmanuel Macron has called for something similar. De Croo built on this in January 2024 when he addressed the European Parliament to present the priorities of his presidency and proposed a European Industrial Deal based on “carrots” for industry to help it develop a ‘green economy’ and compete with China and the US, especially since the latter’s US Inflation Reduction Act. These carrots include false solutions to the climate crisis such as hydrogen and carbon capture and storage, as part of the ‘net zero’ agenda. Net zero has been labelled a “big con” by Corporate Europe Observatory and other green groups, an attempt by polluting industries and supportive governments to escape responsibility to act to address climate change or to repair the damage imposed on ecosystems and frontline communities.

Cartoon by @CartoonRalph

Other components of an Industrial Deal could include a commitment to avoid a heavier legislative ‘burden’ for industry and support for affordable energy prices (but only for industry, not ordinary consumers). Such demands are all couched in the framework of strengthening the EU Single Market, and industry demands a new Commissioner role to deliver it all.

So industry has rung the (false) alarm bell about the Green Deal, and right-wing politicians at the EU and member state levels have responded accordingly. The von der Leyen Commission has shifted emphasis away from a full implementation of the Green Deal elements, the CSS and Farm to Fork. Promises to reform REACH, cut pesticide use, and to stop the export of already banned hazardous substances, have been abandoned or kicked into the long grass. Instead, and with more than an eye on the upcoming European elections and renewal of her personal mandate as Commission President, von der Leyen is joining with De Croo and others to reward the Big Toxics sector, alongside other industries, with a European Industrial Deal.

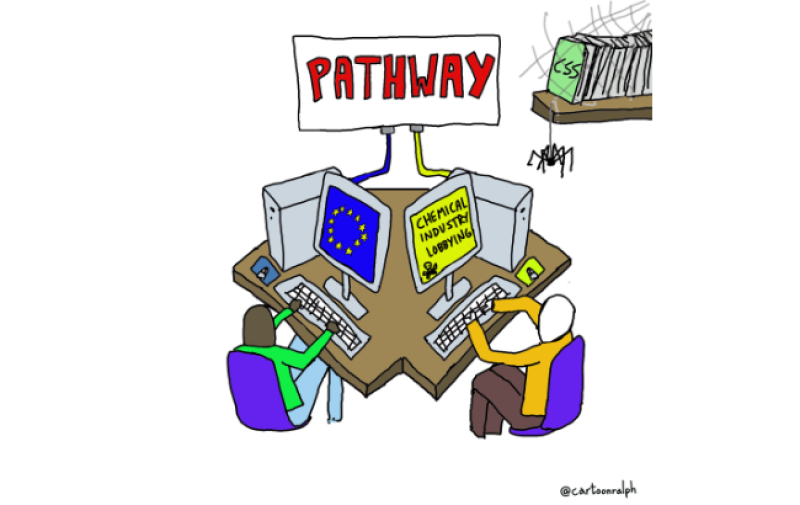

Cartoon by @CartoonRalph

CEFIC as the voice of the EU chemicals industry has played its hand well. Its most vocal and conservative members such as VCI have been prominent in criticising the chemicals strategy and plans for the REACH revision. Meanwhile CEFIC likes to portray itself as a constructive partner to decision-makers, expressing rhetorical support for the goals of the CSS, but the devil is in the details. For example its detailed lobbying proposals such as on essential use in reality would thoroughly undermine any ambitious plans to tackle hazardous chemicals.

“Constructive partner” is how Martin Brudermüller, CEFIC’s president and BASF’s chief executive described CEFIC’s role when he concluded a meeting with the Commission in January 2021. This position is strategic for CEFIC; it wants to be as close as possible to those drafting policy, to appear constructive and a provider of solutions, in order to keep its legitimacy and a seat at the table. And DG Grow officials seem amenable: at one point in this meeting, officials said it would develop aspects (including definitions to be used) “in partnership especially with Cefic”.

This close relationship is exemplified by a Commission document 'Transition pathway for the chemicals industry' launched in February 2023. The pathway has a different purpose to the CSS. The CSS (co-launched by DG Environment and DG Grow) set out the Commission’s ambition towards a toxic-free environment and emphasised action to phase out hazardous chemicals, for example, in consumer products, and to replace them with safer alternatives. The CSS was supported by all member states. By contrast, the pathway (led by DG Grow, without the collaboration of member states) does not pay serious attention to the urgent need to develop and substitute hazardous substances with safer chemicals and it has no formal pledges or targets. The implementation has been even weaker, and it seems likely that at least some of the industry projects announced would have gone ahead anyway. Unlike the CSS, the pathway is much more industry-focused: about “improved resilience in the chemical industry”, and delivering on the EU industrial strategy.

According to the European Environmental Bureau, the pathway is vague and lacks an “overall concept”. But by emphasising the pathway, CEFIC and DG Grow have gently diverted attention away from the urgent need to implement the CSS. No wonder then that CEFIC declared itself to be “very happy” with the pathway. In fact it claims to have “asked the Commission” to develop it and "co-created" it together. Its implementation is also undertaken with the chemicals industry, including CEFIC, as since March 2023 it is the subject of a DG Grow working group, made up of 18 representatives of industry, but only 5 NGOs and 1 trade union representative.

Cartoon by @CartoonRalph

And this seems to be the direction of things to come. Instead of tough regulation to restrict hazardous chemicals (ie the REACH revision, export ban, and the restriction on pesticides), we see industry “pathways”, and calls for an “Industry Deal” as the planned output of tomorrow’s event in Antwerp. The chemical industry’s strategy to seemingly embrace the ‘green economy’ while in reality mobilising against strong action on health and biodiversity, promoting vague non-binding proposals, financing its own impact studies to try to delay action, and demanding financial support, is paying off.

When the CSS was first introduced, it was clear that its ambition would have major implications for the chemicals industry and its products. Soon after, CEFIC contracted the consultancy Ricardo, a consultancy with long experience in the chemicals sector and in conducting ‘impact assessments’ for both the private sector and the Commission. Ricardo is also a regular at networking events on chemical issues, such as the 2023 ChemCon Conference, which was described as “a good mix of regulators and industry experience” by a Syngenta (pesticides) representative.

Ricardo’s task was seemingly to develop an impact assessment on aspects of the CSS which could be used in the Commission’s own impact assessment. In particular the study looked at the impact of the proposed REACH revision to extend the ‘generic approach to risk management’ and introduce new hazard classes, both steps towards a ban on the most harmful chemicals in everyday and professional products, and to better communicate to workers and citizens about the hazardous chemicals present in the products they use.

Under so-called ‘Better Regulation’, which Corporate Europe Observatory has called “deregulation in disguise”, every legislative proposal the Commission produces must be accompanied by an impact assessment, already scrutinised and signed-off by its Regulatory Scrutiny Board. While the concept of assessing impacts sounds neutral, in fact the idea originated with the tobacco industry in the 1980s and 1990s, keen to dilute health concerns about its killer products with analysis about how its profits would be hit by anti-smoking rules. Today, impact assessments too often suffer from the same bias, that economic benefits for business and costs of new rules are easier to map and quantify than social or environmental ones.

Increasingly we see impact assessments being commissioned by industry as a lobby tool, sometimes developed using the Commission’s problematic ‘Better Regulation’ rules for its own impact assessments. Industry’s studies can be presented as ‘helpful’ contributions while the legislative proposal is being produced; and to scare officials away from the most ambitious green legislation which might hit industry profits. Presented as expertise, the scope of the assessment can provide a biased picture of the consequences of a proposed EU law. For example, the pesticide industry’s coordinated use of impact assessments to sabotage the proposed pesticide reduction regulation is analysed by Corporate Europe Observatory here.

A lobbyist for EU lobby firm Fleishman Hillard, whose major clients include CEFIC, sets out the use of this lobby tool clearly: “If you want to influence what the Commission propose, the best thing is to mirror your submission in the form of a good Impact Assessment – a shadow impact assessment. ... Of course, you’ll follow the Better Regulation Guidelines to the letter [and] hire someone the Commission use in your area. ... The Commission may well just co-opt your evidence, thinking, and options.”

The CEFIC impact assessment included a “rapid literature review”, with occasional references to academic research. However most of its findings come from answers from big businesses (as small and medium enterprises lacked resources to provide input for the study), to consultations on their perceived impacts from selected actions from the CSS. This was a specific approach and a frame tailored to lead to a selective conclusion. The impact assessment enabled CEFIC to claim that “as many as 12,000 substances out of 24,000 registered” could be affected due to the CSS. According to the assessment, this would affect up to 43 per cent of the European chemical industry’s total turnover, would represent a net market loss of at least 12 per cent of the industry’s portfolio by 2040, and would lead to 40,000 job losses.

Journalists reproduced these striking figures incessantly: for example the ‘12,000 chemicals’ figure was used by influential media outlets, such as the Financial Times and Euronews, and many others during 2022. In articles in the Financial Times, the figure of '40,000 job losses in Europe’ was also mentioned, a strong argument to influence politicians against regulation. And to make sure decision-makers had these scary figures on their radar, CEFIC sponsored content in Politico in December 2021 to reinforce its lobby agenda.

Politically, the impact assessment also gained traction. A day before its publication in December 2021, the study was presented to the Commission including members of important cabinets (von der Leyen, Breton (Grow), Kyriakides (health), and Sinkevičius (environment)). The study was also promoted in many lobby meetings including in one meeting between Marco Mensink (Director General of CEFIC) and the Cabinet of then Commission Vice President Timmermans, and in another meeting between Brudermüller and Michael Vassiliadis (trade union federation IndustriALL President), with Commissioner Schmit (employment). From December 2021 until September 2022, CEFIC impact assessment figures were shared in at least 10 lobby meetings with high-level representatives of the Commission, although this figure is likely an under-estimate.

Crucially the Commission’s own impact assessment for its proposal to revise REACH cited the Ricardo/CEFIC study in its references. However the heavy redactions in the Commission’s own impact assessment (which have been labelled “maladministration” by the EU Ombudsman) do not allow us to understand to what extent the CEFIC study has informed the Commission’s own assessment.

Not only did Brudermüller travel to Brussels to reinforce the CEFIC impact assessment figures in the minds of senior politicians in Europe, he also presented the transition pathway to the prime ministers of the Slovak Republic, Spain, Finland and the Netherlands. These meetings are only known to us thanks to his social media postings.

Half of chemical substances affected (12,000), 40,000 jobs, 43 per cent of turnover, etc. Those figures became the industry figures in lobby meetings and articles on the predicted impacts of the CSS. But those figures are CEFIC figures, numbers which formed part of its lobby strategy. And at some point, doubts about them started to creep into the discussions.

The Commission, after taking a closer look at CEFIC impact assessment, started questioning it. Indeed in June 2022, seven months after Ricardo published the impact assessment paid for by CEFIC, the director for chemicals of DG Grow told the German Chemical Industry (VCI) that “we take the figures very seriously, even if they reflect many things that the Commission does not intend to do, or perhaps only in the distant future” [emphasis added]. In September 2022, the cabinet of the then Commissioner for the Green Deal Frans Timmermans pointed to the assumptions, which seem to go beyond Commission’s plans, and asked why the study did not look at the health and environmental benefits, nor at the business opportunities from the transition to safe and sustainable chemicals. The report “Waiting for REACH” by the European Environmental Bureau and CHEM Trust made similar points.

This is all very reminiscent of the past. In 2003, when the original REACH proposal was being debated The Guardian quoted Eggert Voscherau, then President of CEFIC as saying: “We are in effect going to de-industrialise Europe [with these proposals]. Several studies commissioned by the chemicals industry and by the Commission show that the costs will go into billions of euros. On top of this there are likely to be significant GDP drops and correspondingly high job losses that are put at hundreds of thousands to up to two million.” The economic success of the chemicals industry since then shows how wrong the doom-mongers were.

The tendency of the chemicals industry to cry wolf should be a warning against taking its hyperbole seriously. Swedish NGO ChemSec wrote a detailed report on this very topic in 2015 and concluded that, among other faults, the chemicals industry consistently underestimates the benefits that it would gain from progressive environmental policies and a shift to safer chemicals.

And that’s not to mention the gains that we would all receive from such a shift. Estimating just some of the health-related costs of Europe-wide exposure specifically to PFAS ‘forever chemicals’ in a single year gives a tally of €52-84 billion. These costs are all too real, and being borne by the public, not companies’ balance sheets.

Cartoon by @CartoonRalph

CEFIC has indicated that it will also work on an impact assessment on the proposed universal restriction on PFAS ‘forever chemicals’. It will be crucial for this study to be independently scrutinised when it is launched; we already know that CEFIC’s PFAS sector group 'FluoroProducts and PFAS for Europe' or FPP4EU is actively lobbying on the dossier. FPP4EU calls for “time unlimited derogation on PFAS used in industrial settings”, that the proposal should address “primary and secondary financial impacts”, and “take into account the drive for a competitive, resilient and sustainable Europe”. In other words, the lobby representing 13 of the biggest PFAS industry players wants an unending opt-out from the ban for industrial uses of PFAS and a focus on economic interests when regulating these harmful chemicals. Sound familiar?

We contacted CEFIC in advance of publishing this article and it did not respond.

It is clear that the CEFIC impact assessment helped contribute to the narrative that the CSS would be too much, too quickly for the chemicals industry to cope with. This merged with the political right’s opposition to a revision of REACH, and other proposals contained in the Green Deal, and helped lead to the current outcome: a REACH revision kicked into the long grass of the next Commission. This result, alongside the development of the transition pathway, hand in hand with DG Grow, will be seen as successes in the eyes of much of the industry.

But for citizens and communities wanting tough action on the toxics and biodiversity crises, industry is off the hook for now, and not being properly held accountable for its corporate decision-making to produce and use hazardous substances.

Cartoon by @CartoonRalph

Seen in this light, tomorrow’s hobnobbing event between CEFIC, industry allies, and EU leaders, is a natural extension of the cosy relationships that already exist. It’s particularly ironic that the event is happening in Flanders, with Belgium experiencing the highest level of PFAS pollution in all of Europe, including in Zwijndrech, near 3M’s plant. There, local residents have been advised to stop eating fruit, vegetables and eggs produced in the vicinity.

De Croo’s championing of industry’s agenda threatens to put back action, not just on the toxic pollution and biodiversity crises, but also on the climate crisis too.

It’s time to challenge this privileged access. It’s long overdue for member states and the EU institutions to review their links and contacts with the chemicals industry. And we need serious independent scrutiny of corporate impact assessments, given their history of being used as lobby tools. Politicians should move to a far more arms-length relationship that leaves decision-makers protected by a lobby firewall and better able to scrutinise industry claims. It’s time for toxic-free politics.

Cartoon by @CartoonRalph